Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The Detainees and the Stories They Told Me

by Mahvish KhanIn My Guantanamo Diary, author Mahvish Rukhsana Khan,

daughter of Afghan immigrants, takes the reader into the

lives of the detainees of Guantanamo Bay. As an interpreter

and part of the law team for the detainees, the author's

point of view is one of a fact finder, but as she speaks and

gets to know the prisoners, it turns into one of sympathetic

listener, confidant and friend.

Habeas corpus is the law under which detainees can petition

for relief of unlawful imprisonment. The legal teams that

represent the prisoners are referred to in the book as

habeas counsel. The habeas counsel encountered many hurdles

in gaining access and time to defend their clients. On

occasion, they were made to stand and wait outside in the

full sun for up to two hours before being allowed in to talk

with the detainees. In 2004, the lawyers were permitted to

visit their clients up to sixty-three hours per week, but as

time went on, the number of days and hours per day for

client lawyer visits shortened considerably.

The author states that there are dangerous prisoners at

Guantanamo Bay, but most of the people she interviewed she

believes have been wrongly jailed. Some of these people

include:

Soon after the September 11th attacks, the

United States posted rewards in Pakistan and Afghanistan

offering up to $25,000 for the capture of

individuals associated with al-Qaeda or the Taliban. This

created opportunities for shady individuals to make some

cash. According to Tom Wilner of Sherman and Sterling law

firm, 86% of the detainees he interviewed had been seized in

Pakistan and sold into captivity for bounty monies.

The prisoners' stories abound with tales of torture and

inhuman treatment. Regular beatings to the head and body,

sleep deprivation, extended periods of standing, being

stripped naked in front of female soldiers and full cavity

searches are reported by many of the detainees. On a daily

basis, prisoners' legs were chained to their cell floors,

and the men were placed in a seven by eight foot cage or

left in solitary confinement with no light or windows for

days on end. Many detainees attempted suicide and went on

hunger strikes, disheartened by their daily treatment, the

lack of justice and the belief that they would never be

released.

The author takes a trip to Afghanistan to collect evidence

on behalf of the detainees she and the habeas counsel are

representing. During her visit, she marvels at the beautiful

landscape of the country and the detainees' families treat

her with great hospitality. Yet, they are devastated by

their loved ones continued unjust imprisonment and in some

cases, their untimely deaths.

Throughout the book, facts are given and stories are told.

In general, the author seems to be compassionate to many of

the Afghan detainees. Only after reading the book, can one

mull over the facts, do further reading and decide what

really has taken place at Guantanamo Bay.

Habeas corpus (Latin for "you may have the body"),

also known as "The Great Writ", is a law that requires a

person detained by authorities to be brought to a court of

law so that the legality of his detention can be examined.

The name is taken from the opening words of the writ (law)

in medieval times. The Habeas Corpus Act was enshrined in

British law by Parliament in 1679 but is thought to have

been in common law for many years before, possibly as far

back as the pre-Norman conquest Anglo-Saxon era. It's

original use was as a writ to bring a prisoner into court to

testify in a trial. What began as a weapon for the king and

courts now offers protection to the individual against

arbitrary detention by the state.

The right to petition for a writ of habeas corpus is one of

the fundamental safeguards of individual liberty but, in

most countries, the procedures of habeas corpus can be

suspended in time of national emergency. The November 2001

Presidential Military Order gave the US President the power

to detain terrorist suspects as unlawful combatants, who

could be held indefinitely without charges being filed and

without entitlement to a legal consultant. Many legal and

constitutional scholars contended and still contend that

this is in direct opposition to habeas corpus and the Bill

of Rights.

In June 2008, the Supreme Court ruling in Boumediene v. Bush

recognized habeas corpus rights for the Guantanamo

prisoners. However, just a few weeks later, the 4th Circuit

Court gave the President the power to arrest and detain U.S.

citizens on native soil indefinitely.

The Guantanamo Bay Military Prison

Since the beginning of the current war in Afghanistan,

it is estimated that about 775 detainees have been brought

to the military prison in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba; of which

approximately 420 have been released without charge.

Some US officials have claimed that some of the released

prisoners returned to the battlefield having tricked their

detainees into believing they were innocent villagers.

One released detainee, Abdallah Salih al-Ajmi, did commit a

successful suicide attack in Mosul in 2008. In January

2009, The Pentagon said that it had evidence that 18 former

detainees had direct involvement in terrorist activities and

a further 43 had plausible links; but according to CNN

analyst Peter Bergen, some of those 'suspected' of returning

to terrorism are so categorized because they publicly made

anti-American statements, "something that's not surprising

if you've been locked up in a U.S. prison camp for several

years."

On January 22, 2009 the White House announced that President

Barack Obama had signed an order that would shut down the

prison in Guantanamo Bay within a year. The challenge

now facing the US is where to house the long-term prisoners

who are genuinely dangerous, and how to find

homes for the prisoners who have been cleared of charges but

who cannot be returned to their own countries for fear of

ill-treatment. About 50 of the remaining 240 prisoners

fall into this category, including the

Uighurs (pronounced wee-gurs), a Muslim ethnic minority

who were cleared for release in 2004 but cannot return to

their home in the far west of China. The men were

captured in Pakistan and Afghanistan but they claim they

were never enemies of the US but were simply fleeing Chinese

oppression (a valid concern in the light of this week's violence, some might say massacre in Urumqi). Last month, four Uighurs were resettled in the British territory of

Bermuda, and the Pacific island nation of Palau has

agreed to take the remaining thirteen.

For a brief history of the Guantanamo Bay military

base, see the sidebar to Dan Fesperman's

The Prisoner of Guantanamo Bay.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in August 2008, and has been updated for the

July 2009 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in August 2008, and has been updated for the

July 2009 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked My Guantanamo Diary, try these:

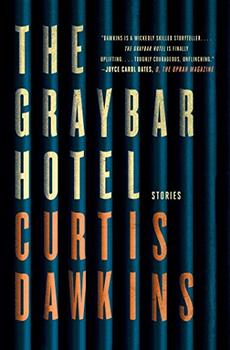

by Curtis Dawkins

Published 2018

In this stunning debut collection, Curtis Dawkins, an MFA graduate and convicted murderer serving life without parole, takes us inside the worlds of prison and prisoners with stories that dazzle with their humor and insight, even as they describe a harsh and barren existence.

by John Paul Rathbone

Published 2011

The son of a Cuban exile recounts the remarkable and contradictory life of famed sugar baron Julio Lobo, the richest man in prerevolutionary Cuba and the last of the island's haute bourgeoisie.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.