Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

From Village to City in a Changing China

by Leslie T. ChangConsidering the articles in recent years regarding toy

recalls or melamine-tainted milk products, Factory Girls

serves as a timely reminder of the human story behind the

Chinese factories we often view in critical terms. Leslie T.

Chang examines an easily forgotten facet: that factories

represent a chance for millions to leave a rural life in

search of higher wages, to escape traditional expectations,

and to search for adventure—a migratory phenomenon known as

chuqu, "to go out".

The city of

Dongguan

is brought to the foreground through a blend of immersion

reporting, diary excerpts and research. As you would expect,

we're given accounts of what it's like to work in the

factories, but the best chapters detail life outside the

confines of the assembly line and the dormitories: Hustlers

promote pyramid schemes; a self-help author preaches the

practicality of plagiarizing; and Mr. Wu, whose method for

teaching English informs the chapter "Assembly-Line

English", inspires his star pupil to teach despite her lack

of fluency. In the talent market, workers claim to possess

skills beyond their actual experiences. A motivational

speaker remarks that "In a factory with one thousand or ten

thousand people, to have the boss discover you is very hard.

You must discover yourself."

One may be left with the impression that the modus operandi

is one of self-preservation and opportunism, but the author

never gives the impression of moralizing and doesn't write

an exposé of China's problems. If the cast of dynamic

characters seem like those you might imagine in a frontier

town—surviving on their wits, a little suspect of outsiders,

and constantly building, moving or selling snake oil—it is

partly because these are the characters that make for the

most compelling reading; but also because the author notes

that, to some degree, the subjects were self-selecting,

since the ambitious were more open to talking about

themselves.

On occasion, Chang departs from the central themes of

migration and the quest for employment, education and

security to examine her own family history. The attempt to

draw parallels between her grandfather and the factory girls

is tenuous—he was sent abroad for a college degree,

something beyond the financial reach of most girls in China

and certainly beyond the reach of most factory girls. Even

if the motivation to search for a better life was the same,

the differences remain too broad to convince the reader.

Nevertheless, these sections provide a valuable context as

they explore some of the consequences of the Communist

Revolution and the subsequent years of recovery.

The author's rare fallible moments turn into one of the

book's strengths. No mantle of authority is assumed here.

When Chang struggles, we empathize with her, particularly in

the beginning when she hesitates to approach workers on the

street for interviews and experiences emotional victories

and setbacks with the girls. When she seems a little too

pleased with being a native speaker of English, as when she

mentions "all the times strangers had gushed over my

English", it's a forgivable faux-pas—living abroad for years

in pursuit of a story is no easy feat, and indeed, that

willingness to portray oneself in a multi-faceted light,

whether favorable or not, lends an honesty to the voice that

might otherwise become too distant, too austere.

Factory Girls does not propose solutions, nor is it

meant as a comprehensive guide to current trends in the

industry. Instead the author leaves it up to the reader to

draw his or her own moral conclusions. Although some readers

may notice an absence of the more salient controversies

(from the USA point of view) surrounding the factories, such

as extensive discussions on unionization or the lack

thereof, livable wages, or whether or not foreign

corporations should be outsourcing their manufacturing

processes in the first place, the author appears to be

focusing more on the human-interest perspective, and as

such, succeeds wonderfully when it comes to following

Chunming, one of the main subjects, whose journey rivals

that of any fictional protagonist. One of the highlights

occurs when Chang visits Chunming's family. Growing up in a

communal village where privacy is nominal goes a long way

towards explaining the initial loneliness the girls

experience in an anonymous city like Dongguan, but also the

freedom most of them come to appreciate, even when it comes

at a high cost.

Ms. Chang's writing is thoroughly engaging, both serious and

funny in unexpected ways. A pastiche of slogans, Maoist song

lyrics, facts, reportage, sociology and insights, Factory

Girls would interest the general reader as well as those

particularly interested in Asian affairs.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in October 2008, and has been updated for the

September 2009 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in October 2008, and has been updated for the

September 2009 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked Factory Girls, try these:

by Amelia Pang

Published 2022

In 2012, an Oregon mother named Julie Keith opened up a package of Halloween decorations. The cheap foam headstones had been $5 at Kmart, too good a deal to pass up. But when she opened the box, something fell out that she wasn't expecting: an SOS letter, handwritten in broken English by the prisoner who'd made and packaged the items.

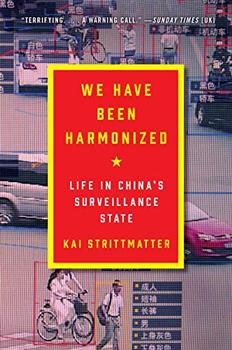

by Kai Strittmatter

Published 2021

Hailed as a masterwork of reporting and analysis, and based on decades of research within China, We Have Been Harmonized, by award-winning correspondent Kai Strittmatter, offers a groundbreaking look at how the internet and high tech have allowed China to create the largest and most effective surveillance state in history.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.