Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

by Toni MorrisonI was quite disappointed by A Mercy. There, I've said it. It feels

sacrilegious to speak ill of such a worthy book and such an exalted author. But

if a novel can be at once worthwhile and disappointing, this one is.

The story begins in a recognizably Morrisonian voice. "Don't be afraid," the

voice says. "My telling can't hurt you in spite of what I have done and I

promise to lie quietly in the dark—weeping perhaps or occasionally seeing the

blood once more—but I will never again unfold my limbs to rise up and bare

teeth." Immediately what springs to mind is the incomprehensibly monstrous deed

at the heart of Beloved, and we wonder: who is this woman and what has

she done? Is Morrison going to take us to a place as terrible as that in

Beloved? At the end of the first chapter, the voice intones, "But I have a

worry. Not because our work is more, but because mothers nursing greedy babies

scare me. I know how their eyes go when they choose." It couldn't be a more

ominous opening.

Over the next spare 155 pages, we are given many stories of horror, cruelty, and

hardship. We learn that the voice belongs to Florens, the 16-year-old slave of

Rebekka Vaark. In a scene which is almost the reverse of the moment in

Beloved when Sethe kills her oldest daughter rather than let her be returned

to slavery, Florens comes to live with the Vaarks when her mother voluntarily

offers her as payment for her master's debt, an abandonment that shadows Florens

for her entire life. Rebekka, whose husband has just died, is also mistress to

Lina, a native woman sold into slavery after her village was sacked, and Sorrow,

an uncontrollable girl who "dragged misery like a tail," a foundling who was

rescued from a shipwreck in which her father was captain and given to the Vaarks

when she became pregnant at age eleven. As if seeking to represent as many

different kinds of people who lived in Virginia in the 1680s as possible,

Morrison rounds out their household with two white men who are indentured

servants and one free African blacksmith who ultimately upsets the precarious

balance of the Vaark farmstead. Each of these characters, with the notable

exception of the black smithy, receives his or her own chapter, and Morrison

presents each of their life stories in compelling prose utterly stripped of

self-pity by the extremity of their circumstances. The remorselessness of the

Atlantic slave trade and the barbarity of colonial life require extraordinary

acts of everyday survival, and some of them are haunting:

"It was Lina who dressed herself in hides, carried a basket and an axe, braved the thigh-high drifts, the mind-numbing wind, to get to the river. There she pulled from below the ice enough broken salmon to bring back and feed them. She filled her basket with all she could snare; tied the basket handle to her braid to keep her hands from freezing on the trek back."

Yet the novel never gets started. The ominous story that Florens promises simply never happens. The action of the novel is confined to just a few days in the spring of 1690, interrupted by deep plunges into history. And the narration of that action is given over to Florens, the only character to speak in first person and present tense. But nothing happens in those few days to warrant the dread of that first chapter. Rebekka falls ill and sends Florens to find the blacksmith, with whom she is passionately in love. He cures Rebekka but fights with Florens, rejecting her for her slavish lovesickness. Morrison gradually reveals that Florens' narration is a love letter to the blacksmith carved on the floor of the Vaark house with a nail. Florens' voice is almost ridiculous in its mixture of high romanticism and clear-eyed naiveté:

"You probably don't know anything at all about what your back looks like whatever the sky holds: sunlight, moonrise. I rest there. My hand, my eyes, my mouth. The first time I see it you are shaping fire with bellows. The shine of water runs down your spine and I have shock at myself for wanting to lick there."

In Beloved, the central horrific act is narrated many times but never

directly. It is reported to the reader in flashes and shards who begins to

"remember" it much like Sethe herself does. But in A Mercy, that same

elision or deferment works against the novel's own purpose. Destroyed by the

blacksmith's rejection, Florens attacks him first with a hammer and then with

his hot tongs, bringing about the blood of the novel's second sentence. But this

seemingly climatic scene is reported to us after the fact, and we never learn

what happens after the blood begins to flow. Florens flees back to the Vaark

household to scratch out her tale, a tale that we never fully experience and

whose point we never quite get. I don't mean to suggest that Morrison's novel

would have been stronger with more melodramatic conflict and bloodshed; instead,

I would have liked to haunt her characters as they perceive their world and make

decisions about how to tame it, rather than simply have their actions reported

to me.

Morrison beautifully, terribly renders the world of America in the 1680s. It is

a world in which it is lawful for a man to beat his wife after nine o'clock, a

world in which the sight of a black girl is still rare enough to cause white

children to scream and white women to cross themselves. But it is a world in

which none of Morrison's characters—black, white or native; free, indentured or

enslaved—have agency, and therefore it is a world without action. Horrific

events and acts of small mercies occur. The characters move, but it is the

zeitgeist blowing through them that animates them. A Mercy is a like a

three-dimensional oil painting that was made to illustrate a point: "There is no

protection. To be female in this place is to be an open wound that cannot heal.

Even if scars form, the festering is ever below."

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in January 2009, and has been updated for the

September 2009 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in January 2009, and has been updated for the

September 2009 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked A Mercy, try these:

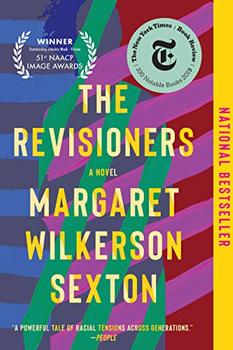

by Margaret Wilkerson Sexton

Published 2020

Following her National Book Award–nominated debut novel, A Kind of Freedom, Margaret Wilkerson Sexton returns with this equally elegant and historically inspired story of survivors and healers, of black women and their black sons, set in the American South.

by Andrea Levy

Published 2011

The author of Small Island tells the story of the last turbulent years of slavery and the early years of freedom in nineteenth-century Jamaica.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.