Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

When we talk about the Holocaust, we often admire the resilience it must have taken to maintain one's dignity in the face of horror. Like many readers, I was first introduced to the literature of the period through The Diary of Anne Frank, and later, through the work of Jewish writers like Primo Levi. I had never considered the German perspective on the Nazis, so when I first began reading Every Man Dies Alone, I wasn't sure what to expect. The novel is not, as I'd imagined, a portrayal of atrocities, though there are certainly beatings and Gestapo interrogations. Fallada doesn't dwell on the more visible signs of war like bombings, marches, or political rallies. Instead, the scale is domestic. Petty opportunism, betrayals, and the strain of family life combine to weave a story that is sometimes frustrating in its meandering, but often revealing in its depiction of a world governed by suspicion.

The novel is divided into four sections: "The Quangels", "The Gestapo", "Things Begin to Go Against the Quangels", and "The End". Anna and Otto Quangel wage a quiet campaign to drop a series of anonymous, antifascist postcards all over Berlin, which serves as the novel's main thread, though over the course of 500+ pages the Quangels' story is often in the background. It intersects with the lives of other families: the Borkhausens, the Kluges, the Persickes, the Hergesells. These and other characters all figure more or less prominently in different chapters, some reappearing more often than others.

The result is a winding plot that turns Berlin into a small world filled with coincidental, pivotal encounters. Despite these many turns, we gain a foreboding sense of these lives marked by desperation and deprivation, and witness how different individuals either accept or fight against their circumstances. True heroism is scarce -- this novel isn't about grand gestures or redemption as much as it is about human weaknesses, how the intensity of our own desires can lead us to step out of our comfort zones even when our choices may seem foolhardy.

One of the earliest images to appear in the novel is a poster announcing the names of three people sentenced to die for treason. The poster is meant to foreshadow: there's no doubt that the Quangels' anti-Nazi writing campaign will be discovered. Because the threat of capture is always imminent, and because it is more or less self-evident that tragedy will occur, the Quangels' story ends up being less intriguing than the many side stories. We sense the real power of The Führer most effectively when Fallada is writing more indirectly about the other characters' smaller, daily transactions.

In one chapter, a character negotiating the price of a baby carriage is surprised by the seller's insistence on a pound of butter and a pound of bacon as payment, noting "it was illegal to demand fat in exchange for goods" -- a law that may seem unusual to readers unfamiliar with war-time shortages. In another chapter, a Jewish woman's apartment is ransacked for its dry goods and linens. That such mundane items become a source of contention between SS officers and two small-time, bumbling thieves seems incredible, but desperation and greed have the potential to affect anyone.

Every Man Dies Alone contains some unbelievable moments, such as one character's change of heart and suicide after deciding the Quangels' actions were more courageous than his own complicity with the war. Although it isn't a perfect novel, I would recommend it for Fallada's talent in showing us that sometimes the most frightening part of a war isn't dramatic at all -- it's the psychological game, that tension arising from waiting for something to happen, and wondering if it ever will, that slowly begins to wear the spirit down. When Fallada writes "As it was, we all acted alone, we were caught alone, and every one of us will have to die alone... But that doesn't mean that we are alone... or that our lives will be in vain," it's an inspiring testament to lives lived in protest against unspeakable acts.

About the Author

Rudolph Ditzen (1893-1947), one of the most famous German writers of the inter-war era, better known by his pen-name Hans Fallada (the last name comes from a Brothers Grimm tale about a horse with magical powers) produced a substantial body of work during his life - fiction and nonfiction, children's books, journalism and political essays.

Rudolph Ditzen (1893-1947), one of the most famous German writers of the inter-war era, better known by his pen-name Hans Fallada (the last name comes from a Brothers Grimm tale about a horse with magical powers) produced a substantial body of work during his life - fiction and nonfiction, children's books, journalism and political essays.

In 1938, his British publisher, George Putnam, sent a boat to take Fallada and his family out of Germany but Fallada felt he had to stay. By 1943, his life had fallen apart, plagued by mental illness, his marriage was failing and he was addicted to both alcohol and morphine. Locked up in a Nazi insane asylum in 1944 propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels ordered him to write an anti-Semitic novel. Fallada pretended to do so, but instead wrote three short novels in code. After the war ended, a friend, hoping to inspire him, gave him the Gestapo file of a working-class couple who performed many acts of resistance in Berlin. In less than a month Fallada wrote "Jeder stirbt für sich allein" (Every Man Dies Alone). He died two weeks after the novel was published and was largely forgotten outside of his native country.

Interesting Links

The back story to the book, as explained in a discussion with Han Fallada's son in the Los Angeles Times.

Alan Furst's extensive review in the Canadian Globe and Mail which provides additional detail about Hans Fallada and his other books available in English.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in April 2009, and has been updated for the

May 2010 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in April 2009, and has been updated for the

May 2010 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked Every Man Dies Alone, try these:

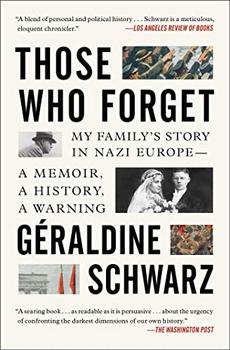

by Géraldine Schwarz

Published 2022

Those Who Forget, published to international awards and acclaim, is journalist Géraldine Schwarz's riveting account of her German and French grandparents' lives during World War II, an in-depth history of Europe's post-war reckoning with fascism, and an urgent appeal to remember as a defense against today's rise of far-right nationalism.

by Maria Hummel

Published 2015

The novel bears witness to the shame and courage of Third Reich families during the devastating final days of the war, as each family member's fateful choice lead the reader deeper into questions of complicity and innocence, to the novel's heartbreaking and unforgettable conclusion.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.