Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

At the beginning of "A Private Experience," two Nigerian women, one Muslim, one Catholic, seek shelter together from a riot; the Muslim woman reaches up to the space around her throat where her necklace had been and says, "My necklace lost when I'm running." Later in the collection, a short story writer buys an ivory necklace, pleased with "the look of the white, tooth-shaped pendant against her throat," and takes pleasure in deliberately offending a smug, politically correct white woman by revealing that it is real ivory. And in the title story, a Nigerian expatriate in America describes how "at night, something would wrap itself around your neck, something that very nearly choked you before you fell asleep." In Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's meticulously detailed stories of Nigerians at home and abroad, national identity functions as both a pendant and a millstone, alternately blessing and burdening its wearers.

One of Adichie's greatest gifts is her ability to sketch the lives of her

characters (mostly women), and to limn the differences between Nigeria and the

United States with a few telling details. Often these women have come to the

United States to join husbands whom they either have not seen for many years or,

as in the case of "The Arrangers of Marriage," have never met before. In

"Imitation," Nkem tries to adjust to living in suburban Philadelphia while her husband, a member of

"the Rich Nigerian Men Who Own Houses in America league," earns money in Lagos. After chatting companionably with her housekeeper, something she would never do in Nigeria, Nkem wryly observes that

"It is what America does to you… It forces egalitarianism on you" even as she has come to love its

"abundance of unreasonable hope." While Nkem's suspicion that her husband is having an affair leads her to decide to move the family back to Lagos, the narrator of

"The Arrangers of Marriage" finds that she would rather endure the misery of her sham partnership just long enough to get a green card rather than return to her family in Nigeria. Her anger at the aunt and uncle who pushed her into the marriage simmers throughout the story, their cravenness captured in a few short lines:

"I had thanked them both for everything - finding me a husband, taking me into

their home, buying me a new pair of shoes every two years. It was the only way

to avoid being called."

A lesser author would take the easy road of broadly painting these cultural differences so that one culture came across as superior to the other, but Adichie seldom falls into this trap. Her expatriates miss Nigeria even as they criticize the way that women are treated there (lecherous uncles, spouses, and employers play prominent roles in these stories) and come to enjoy certain aspects of American culture despite the difficulties of assimilation. The two strongest stories,

"On Monday of Last Week" and "Jumping Monkey Hill," probe even deeper by creating complex characters who address these issues head-on, with nary a shred of didacticism or spoon-fed multiculturalism in sight.

Kamara, the Nigerian nanny in "On Monday of Last Week," finds her first American job looking after a young boy named Josh, the son of a Jewish father, Neil, and an African-American mother, Tracy. Josh quickly takes to Kamara, especially since Tracy's artistic tendencies make her a hands-off parent; at Kamara's job interview, Neil tells her,

"You have to make sure you don't bother [Tracy] for anything whatsoever." Bemused by Neil's over-zealous parenting, Kamara also feels curious about Tracy's mysterious presence until the day that the artist emerges from her cocoon of a studio:

"Their eyes held and suddenly Kamara wanted to lose weight and wear makeup again." We find out that Kamara's marriage to her husband has deteriorated over the years that they spent apart, she in Nigeria while he saved money for her to join him in the United States. This makes Kamara vulnerable to Tracy, who uses her charismatic personality to practically seduce Kamara by demanding,

"You will take off your clothes for me." On the day that Kamara finally gathers her courage to pose for Tracy, however, Tracy coldly pulls the rug from under her, and we see a cold, self-centered woman through the eyes of a lonely woman desperate for love.

"On Monday of Last Week" expertly juggles weighty themes like mixed-race marriages, lesbianism, and immigrant experiences by focusing on character rather than trying to deliver a message.

Likewise, "Jumping Monkey Hill" uses a sophisticated structure and finely drawn characters to convey the power politics at play in the African writing community. The fact that there are no monkeys at this genteel South African resort, the site of a writing workshop for Africa's rising literary stars, casts a dubious light on the enterprise from the beginning. Ujunwa, the Nigerian protagonist, immediately notes the sycophantic relationship between Edward, the white South African leader of the workshop, and the Ugandan, never named, who has won a prestigious literary prize. Indeed, Ujunwa is the only one of the participants to receive a name; Adichie describes the others by nationality (the Kenyan, the Tanzanian) and leavens the otherwise intense tone of the story with a section where they all tease each other about their national characteristics. As the story progresses, Edward's patronizing attitude increases to the point that he derides one participant's story as

"passé" in comparison to Africa's political uprisings and slights another that deals with homosexuality as not

"reflective of Africa." Ultimately, he makes sexual comments to Ujunwa, who says nothing at first, attempting to laugh off the harassment. But Adichie gives us a window into Ujunwa's true feelings by interspersing sections of the story that she is writing for the workshop throughout

"Jumping Monkey Hill," and it is a righteously angry story that will put Edward and his ilk in their place. While the other workshop participants tolerate Edward due to his connections in the literary world, only Ujunwa stands up to him at the end, her story within a story lashing out like a slap in the face of cultural and gender superiority. Or like a pendant shining in darkness, lost and then found.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in July 2009, and has been updated for the

July 2010 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in July 2009, and has been updated for the

July 2010 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked The Thing Around Your Neck, try these:

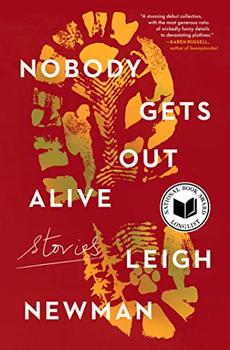

by Leigh Newman

Published 2023

From the prizewinning, debut fiction author: an exhilarating virtuosic story collection about women navigating the wilds of male-dominated Alaskan society.

The Office of Historical Corrections

by Danielle Evans

Published 2021

The award-winning author of Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self brings her signature voice and insight to the subjects of race, grief, apology, and American history.

Finishing second in the Olympics gets you silver. Finishing second in politics gets you oblivion.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.