Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Change is something we all accept as part of contemporary life, so the apparent rigidity and stasis of the ancient Egyptian state is difficult for us to grasp today. Over three thousand years of recorded history, from the emerging authority of the so-called King Scorpion to the final days of doomed Cleopatra, ancient Egypt shows a remarkable continuity in its culture, language, and mode of governance. What was the reason for the inviolacy of their core beliefs, and why, when so advanced, vigorous, and innovative, did they choose to remain mired in their own well-worn rituals and decaying social order when the rest of the world, slowly at first, began to develop their own dynamic civilizations?

To Dr. Toby Wilkinson, an impressively credentialed Egyptologist, asking these questions is essential to understanding ancient Egyptian history and, in his doorstopper-length work The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt, he proposes a relatively simple, sensible answer: the history of ancient Egypt is the history of a small, narrowly concentrated group of elites brutally exercising their power over a whipped, starved, and constantly downtrodden populace. He states this argument, more or less, right in his introduction:

"From human sacrifice in the First Dynasty to peasant revolts under the Ptolemids, ancient Egypt was a society in which the relationship between the king and his subjects was based on coercion and fear, not love and admiration - where royal power was absolute and life was cheap."

If you can accept this thesis, and can also accept Wilkinson's occasional overstatement of it, then you will find The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt not only a satisfying and comprehensive survey on ancient Egypt but also a narrative tour de force dramatically following the deeds and misdeeds of thirty centuries of Pharaohs, priests, architects, generals, barbarians, peasants, and rebels. General audiences should have no problem being engrossed by this book, though the reader should keep in mind what to expect from historical writing.

Wilkinson approaches Egypt through the lens of modernity. He constantly compares the rulers of ancient Egyptian to modern day dictators; Hitler, Stalin, Kim Il Sun, and Nicolae Ceausescu are mentioned in discussing the kind of rule the Pharaohs provided. To Wilkinson, all aspects of the Egyptian culture were informed by the dictatorial, authoritarian nature of the monarchy. Religion, deeply integral to the native Egyptian way of life, was a means to power; while the priesthood, in Wilkinson's eyes, was closer to a tax shelter than a sacred institution. Even Egypt's great monuments, its pyramids and tombs and great temples, were nothing more than symbolic representations of the Pharaoh's total control over his subjects. One particularly striking passage underlines the author's attitude towards the grand monumentalism of the Egyptian society; describing the royal palace of the Pharaoh Akhenaten, he pauses on the floor decoration in the main courtyard:

"The main route used by the king had a plastered pavement painted with images of foreigners. This allowed Akhenaten to trample his enemies underfoot as he went about state business - 'the unselfconscious trumpeting of official brutality.'"

Readers who have read much about Russian history or the French Revolution may notice a familiar tendency in this work, a desire on Wilkinson's part to paint the state in question as a villainous autocracy and then, having deemed it as such, to moralize on its failings. This is not enough to ruin all of his good, detailed work or to derail the fast-paced, no-time-to-catch-a-breath narrative, but it can make the book seem rather one note at times. At these moments, I wished Wilkinson had developed a more well-rounded picture of the culture rather than hammer on one aspect constantly.

The best parts of the book come as the Egyptian empire begins to fall apart; here Wilkinson can only accuse the native rulers of incompetence and not outright totalitarianism. Instead of following the increasingly irrelevant native kings, he extends his focus to include the outside invaders who, one after another, would come to gain and lose control over the Egyptian state. Here are exotic and scarcely-understood peoples; the hording, disorderly Hyksos, the mysterious Sea People, the exotic, agnostic Libyian chiefdoms, the half-Egyptianized Kushans, the expansive, paternalistic Persians, and finally the fractious, incestuous Greek dynasty of the Ptolemies. All these groups come and go from the story relatively quickly, but, perhaps for the very reason that their motives can be less easily parsed, they all seem more well-rounded and human than do the book's primary subjects. The end of Egypt's story - the rise of Rome, Cleopatra, and so forth - is more alive with human drama than any other part of the book, and through those events the reader is shown how Egypt becomes part of the Roman Empire and how its history enters the larger stream of the history of the West. A small coda details how Napoleon's conquests invigorated Egyptian studies and how resonances from that time still inform our lives today. In the end, Wilkinson's ancient Egypt is one of anxiety and terror, and there is not a chapter in the book that does not reinforce that sentiment. In his unsentimental and distinctly modern telling of the story of Egypt, however, I feel for the first time that I can approach ancient Egypt not as a jumble of myth but as a real, living, human society.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in March 2011, and has been updated for the

January 2013 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in March 2011, and has been updated for the

January 2013 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt, try these:

by Daisy Dunn

Published 2024

A dazzlingly ambitious history of the ancient world that places women at the center—from Cleopatra to Boudica, Sappho to Fulvia, and countless other artists, writers, leaders, and creators of history

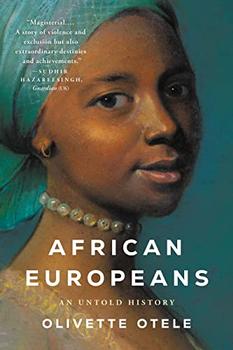

by Olivette Otele

Published 2023

A dazzling history of Africans in Europe, revealing their unacknowledged role in shaping the continent.

Discovery consists of seeing what everybody has seen and thinking what nobody has thought.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.