Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

by Monique RoffeyOn the fateful day that newlyweds George and Sabine Harwood disembark from the ship that has transported them from their comfortable lives in England to a newly liberated Trinidad, a cluster of ravens circles the harbor, boding ill for their island adventure.

Throughout this sensuous and deeply sad novel, the motif of flight asserts an ominous presence in many forms - floating ash appears in Sabine's dreams as the reverse image of snow ("black flecks... against a blanket of white"), a fancy hat reminds George of a dead raven, and, in a technological twist, a blimp orbits the island, silently spying on its citizens for unknown yet widely speculated reasons. Each of these examples delineates Sabine's unhappiness in Trinidad, which is both instant and life-long.

Bird imagery even extends to the real-life popular calypso singer dubbed the Mighty Sparrow, though he represents social change and entertainment rather than bad luck. The shrill call of the aptly named kiskadee seems to repeat the question, "Qu'est-ce qu'il dit?" (What does he say?) in Sabine's native French, which takes on immense meaning as a reminder of the male discourse that surrounds Sabine throughout the novel. We watch her both absorb and reject this discourse as we trace Sabine's trajectory from a young wife who dotes on her husband's every word to an embittered woman who places her withering hopes in the fiery rhetoric of Trinidad's first black prime minister, Eric Williams.

Monique Roffey, a Trinidadian now living in London, portrays her homeland as a fertile seductress, its hills personified as the "green woman" to whom Sabine loses her husband's affection. After a powerful rainstorm (the result of the green woman "shaking her hair"), and feeling alienated by her environment, Sabine confronts the curvaceous mountain in the first of a series of lifelong dialogues with her rival: "I hate you. My husband loves you," laments Sabine. Not surprisingly in this off-kilter world, the sated mountain seems to answer back: "They all love me," it replies.

The initial three-year contract that George signs with his company drags on for five years, seven years, ten, as he buys land for a song, building a fortress for Sabine and their two children, Sebastian and Pascale. They acquire a maid, the loyal and talkative Venus, who acts as a protector and guide to Sabine and as a second mother to the children. But it is Venus's grandmother, a formidable elderly woman called Granny Seraphina, who piques Sabine's curiosity in Eric Williams and his rousing lectures in the town square.

Seamlessly integrating political issues involving race, colonialism, and the legacy of slavery with the more personal conflicts that Sabine and George experience in their marriage, Roffey crafts a novel whose epic scope - the action spans 50 years and is broken down into temporal sections: 2006, 1956, 1963, and 1970 - belies its intimate perspective.

Novels that tackle politics often become unwieldy, threatening to topple under the accumulation of names, dates, and events, but Sabine's shrewd assessment of the transformation that Trinidad undergoes anchors the narrative; her growing empathy with the citizens who suffered under colonial rule is tempered by disarming incidents in which she learns that her own racial background makes her a target. Taunted in the town square as "Massa" (Master) and "white girl," threatened by a masked man at Carnival, and pelted with stones during a Black Power uprising, Sabine finally makes the choice to leave Trinidad. When her housekeeper Lucy tries to persuade her to stay, Sabine eloquently sums up her decision: "Lucy, we have to go. People like us, we're not wanted here. We're part of the problem. Trinidad is changing. It must change."

Acknowledging these complexities prevents the novel from becoming a one-sided apologia for colonialism or a radical screed promoting violent revolution. Sabine may not always be a likable character, but her political savvy, in contrast to George's disinterest in anything that undermines his rosy view of paradise, steers us through Trinidad's dynamic upheaval.

While The White Woman on the Green Bicycle undoubtedly deserves its place in the annals of contemporary Caribbean fiction, it also heralds a new entry in the catalog of strange-woman-in-a-strange-land narratives that encompasses such classics as Black Narcissus by Rumer Godden (1939), The Grass is Singing by Doris Lessing (1950), and Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys (1966). Like the heroines of these novels, Sabine valiantly strives to accommodate a new life that challenges her very sense of self and thwarts her desire for flight.

![]() This review

first ran in the May 12, 2011

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This review

first ran in the May 12, 2011

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

If you liked The White Woman on the Green Bicycle, try these:

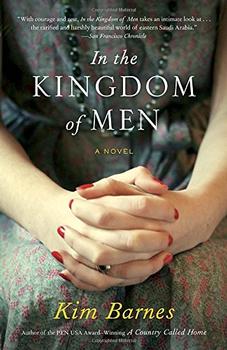

by Kim Barnes

Published 2013

From the PEN USA Award-winning author of A Country Called Home, a richly imagined new novel about a young woman who leaves the dusty farmland of 1960s Oklahoma to follow her husband to the oil fields of Saudi Arabia and finds a world of wealth, glamour, American privilege, and corruption.

The Secret History of Costaguana

by Juan Gabriel Vásquez

Published 2012

Tragic and despairing, comic and insightful, The Secret History of Costaguana is a masterpiece of historical invention.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.