Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

It's tempting, when reading the memoir of a novelist one admires, to spend time combing through the details of the author's life hoping to find the seeds of inspiration for his or her fiction. Certainly there are moments in Paul Auster's new memoir Winter Journal where this project can bear fruit - such as the lengthy film synopsis which is one of Auster's trademarks, or the passage where he writes "that is how you see yourself whenever you stop to think about who you are: a man who walks, a man who has spent his life walking through the streets of cities." This passage will resonate with anyone who's read Auster's novel City of Glass, which centers on the idea of walking through the streets of cities.

Sooner or later, though, it's worthwhile to put this project aside and instead focus on Winter Journal for what it is, namely a thoughtful, elegiac meditation on the body that moves through those streets - its movements, its pleasures, its crises, its eventual deterioration and death. It's interesting that Auster, a writer whose novels are sometimes criticized for being too cerebral, should focus his memoir so intently on the physicality of the body rather than the life of the mind.

Winter Journal is, literally, a winter journal. Auster wrote it during the first months of 2011 as he approached his sixty-fourth birthday, and while New York City was buried under a series of debilitating blizzards. It's also, of course, a reflection on what it means to come to the winter of one's life, to come to terms (or not) with the fact that the inevitable end approaches: "Even as you approach the age of your father when his life came to an end, you have not called any cemetery to arrange for your burial plot, have not given away any of the books you are certain you will never read again, and have not begun to clear your throat to say your good-byes." Winter Journal appears, in many ways, to be Auster's attempt to write through this denial, to reflect on the history of his body - on where it's been and on where it's eventually going.

At times Auster's tendency toward list-making can grow nearly tiresome, such as when he recalls, in order, each of the houses in which he's been a permanent resident, or when he embarks on a slightly-too-long litany of the mundane things one's hands do every day. Winter Journal is far more than a simple collection of lists, however; the memoir is strongest and most emotionally compelling when the reader can see Auster arriving at moments of revelation, such as the realization that his moments of periodic physical frailty coincide closely with episodes of emotional intensity, personal crisis, and loss. Once this pattern has been identified, it's fascinating to trace it through his life, to consider what this synthesis of mind and body means not only for Auster but also for the lives and bodies of others.

Auster writes Winter Journal in the second person, referring to himself throughout as "you." This technique can prove awkward and almost forced at times. Overall, however, the second-person narration offers an effective way to force readers to consider their own feelings about aging, death, and the life of the body. For, when he asks questions like "Sneezing and laughing, yawning and crying, burping and coughing ... running your hands through your hair - how many times have you done those things?" he's asking this question not only of himself but also, implicitly, of his readers, encouraging them to not only empathize with his writing but also to move past their denial of their own bodies' movements through space and time, their own journey toward life's winter.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in October 2012, and has been updated for the

November 2013 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in October 2012, and has been updated for the

November 2013 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked Winter Journal, try these:

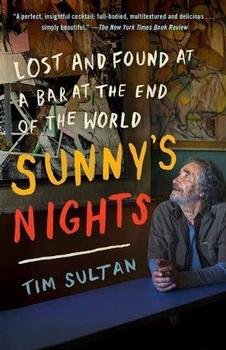

by Tim Sultan

Published 2018

Imagine that Alice had walked into a bar instead of falling down the rabbit hole. In the tradition of J. R. Moehringer's The Tender Bar and the classic reportage of Joseph Mitchell, here is an indelible portrait of what is quite possibly the greatest bar in the world—and the mercurial, magnificent man behind it.

by Heidi Julavits

Published 2016

A raucous, stunningly candid, deliriously smart diary of two years in the life of the incomparable Heidi Julavits

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.