Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

For the last several years, one of my favorite bands has been Cloud Cult. Their upbeat lyrics and peppy melodies belie a darker past, one characterized by the sudden death of the lead singer's very young son. Since that time, much of what Cloud Cult has sung about is this loss and what comes after. As I read Emily Rapp's shattering new memoir, The Still Point of the Turning World, I was reminded of Cloud Cult, and marveled again at the desire - bordering on compulsion - of so many artists to record this experience of grief and loss, not to capitalize on it but because they have no choice.

When Rapp's son Ronan began missing his developmental milestones shortly after his six-month birthday, Rapp and her husband took him to an ophthalmologist who confirmed their worst fears - Ronan had Tay-Sachs disease, a genetic enzyme deficiency with no known cure and the prognosis of rapid neurological decline and certain death within months or very few years. Following the expected - and completely justified - raging and weeping in the wake of this catastrophic diagnosis, Rapp focused on two things: mothering her son as best she could in the time they had left together, and drawing on her considerable knowledge of philosophy, religious traditions, and literature in an attempt to make sense of the unfathomable.

Recalling what it felt like to contemplate writing in those first days and weeks following her young son's diagnosis, Rapp says, "I am a writer. I write. And just as I had written through every experience, euphoric or horrific, throughout my life, I began to document the daily happenings of my son's short life. Once I started I didn't - I couldn't - stop." Rapp examines her son's all-too-brief life - and her own reactions to it - fearlessly and with an honesty that will devastate and astonish not only other parents, but everyone who opens this remarkable book.

As Rapp begins to connect online and in person with the small handful of other parents coping with imminent or recent losses due to Tay-Sachs and related diseases, she dubs them "dragon parents," parents who are doing their jobs without models and without nets. Gone are Rapp's hopes and expectations that her son will attend a prestigious college or master a musical instrument or even learn to walk. Instead, she is left with the unexpected duty and, at times, surprising delight of just being with her son, of imagining his life not as a progression toward some imaginable future but as a series of infinitely small present moments, unrelated to what has come before and after. "That was my role as a dragon mother," she writes," to protect my child from wickedness and as much suffering as possible and then, finally, to do the hardest thing of all, a thing most parents will thankfully never have to do: let him go."

Rapp's thinking about Ronan is informed both by her own personal history - she wears a prosthetic leg after a congenital birth defect resulted in the amputation of her leg as a young girl - and by her rich background of reading and writing. Rapp, whose previous memoir (Poster Child) dealt to a large extent with issues of difference, disability, and humanity, considers many of the same issues here, as she addresses seemingly unanswerable questions about genetic predetermination, fate, and the reaction of "normal" people to issues of disability and, in the case of Ronan, imminent death. Rapp intersperses her own gut-wrenching prose (one particularly moving litany on grief reads in part, "Grief is...Waiting for someone to change the subject / Ink spilled on white pants or a white sheet: ink from a pen, ink from a squid, blue-black and slimy / Sighing a lot / Feeling naked in private and feeling private in public / Running amok") with the words and wisdom of others, including the poets Seamus Heaney and Wislawa Szymborska, the philosopher Georg Hegel, the Christian apologist C.S. Lewis, and particularly the novelist Mary Shelley, whose Frankenstein Rapp returns to again and again, approaching it from various directions. Rapp's memoir manages to be simultaneously personal and erudite, and its numerous allusions do not distance the reader from the powerful emotions at hand but rather encourage delving ever deeper into the painful and provocative questions she raises.

As she wrote this memoir, Rapp chronicled her son's life in a blog called Little Seal, which has already brought hundreds of thousands of people to Ronan's story and to Rapp's exquisite contemplation of it. Ronan died while I was reading the memoir, just a few weeks shy of his third birthday. Outpourings of grief continued to spread across the Internet for this boy most blog readers never knew, and for his mother who has, through his story, shown us how to think deeply and carefully not only about how to parent and how to love but also about how to be human.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in March 2013, and has been updated for the

March 2014 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in March 2013, and has been updated for the

March 2014 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked The Still Point of the Turning World, try these:

by Allison Pataki

Published 2019

A deeply moving memoir about a young couple whose lives were changed in the blink of an eye, and the love that helped them rewrite their future.

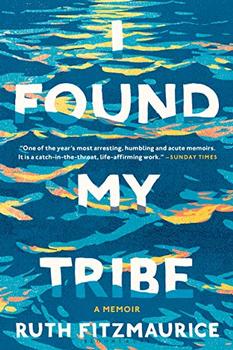

by Ruth Fitzmaurice

Published 2019

A transformative, euphoric memoir about finding solace in the unexpected for readers of H is for Hawk and When Breath Becomes Air.

The secret of freedom lies in educating people, whereas the secret of tyranny is in keeping them ignorant

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.