Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

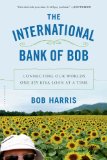

Connecting Our Worlds One $25 Kiva Loan at a Time

by Bob HarrisThe International Bank of Bob is part comic memoir, part informative travel journal, and, because we are introduced to so many people, a little like a speed-dating session. Still the book's organizing principle is simple and humane: The author, Bob Harris, who has made many loans through the micro-?nance loan organization, Kiva.org, decides to travel the world get to know the recipients of his loans. Harris sees how these loans affect their lives, and to meet the volunteers and representatives of Kiva's partners in the field.

Before becoming a micro-financier, Harris reviewed the most sumptuous and expensive food, drink and accommodations available on the planet for ForbesTraveler.com. Among his assignments was a stay at the Burj Al Arab Hotel in Dubai where "the World's Most Expensive Cocktail," at a cost of $7,438, is whisky served in a gold tumbler. The hotel had a vending machine dispensing gold bars, and "[goes] through five kilograms (eleven pounds) of fresh gold annually just in pastry decorations."

The burnished excess of the Burj Al Arab afflicts Harris with "a severe case of wealth vertigo," and leads him to condemn the lack of "humane purpose" in the creation of hundred-dollar pastries. Harris also contemplates "the birth lottery," the arbitrariness of good or bad fortune that gives some people golden cups of Scotch while others, among them Dubai's immigrant construction workers, work twelve-hour days, six days a week, in horrific heat and humidity, for as little a $6 a day if they're paid at all (many must work for nothing for years to earn back labor "contracts.").

Harris resolves to use his earnings to help alleviate poverty from the bottom up, to strengthen struggling third-world economies, and to track what happens to his money. The personal nature of Kiva.org ("You could see the faces of individual people connected to your actions, along with short bios and descriptions of their plans."), as well as Kiva.org's high repayment rate, convince Harris to invest in a series of low-interest Kiva.org loans administered through local micro-finance institutions (MFIs). Harris travels to Peru, Sarajevo, Bosnia, Kenya, Rwanda, India, Vietnam, the Philippines, Cambodia and Beirut to see Kiva's partner MFIs in action and to visit the men and women who have received his loans. He observes their work in hair salons, furniture shops, convenience stores and farms, without their ever knowing that Harris is their lender.

Harris is efficient and thorough in his explanation of micro-lending and its successes, failures and challenges. He is sensitive to the psychology of giving, including the tendency to view the needy as helpless victims, and the numbness and paralysis donors can feel when facing the vastness of suffering and need (still, this doesn't excuse Harris's use of "overwhelm" as a noun.) Harris repeatedly asks the reader to seek a loving connection to others and an affirmative attitude toward experience. However a discussion of current data on the effects of income inequality on health, crime rate, and general well-being would have bolstered Harris' exhortations with powerful facts.

Harris often likens the borrowers he meets in developing nations to members of his own white, Christian middle-American family, and equates their work to work in America. When the Rwandan shop-owner Yvonne "[fiddles] absent-mindedly with a box on the counter ...," Harris must tell us that "[his] own mom used to do the same thing sometimes" and compares her shop to a 7-Eleven. Observing exhausted construction workers in Dubai, Harris remarks, "The faces of the workers I'd seen earlier, echoes of my father's own face, flashed through my mind." I found these comparisons unnecessary, and even annoying.

In addition to endnotes, Harris also provides copious footnotes on a variety of subjects, many of which disrupt the narrative:

"The next day, I told my friend Jane about it, and one of us––neither of us remembers who––started joking that I now officially opened the International Bank of Bob. *" Harris insists on adding the following hardly relevant footnote: "*Jane is a Hugo Award-winning TV writer, some of whose work you may have already enjoyed..."

Although The International Bank of Bob is an engaging and clever title, Harris' purpose would have been better served with something a little less ego-centric. Still, he educates, amuses, and introduces readers to people we're honored to know, all while explaining the sometimes complex workings of micro-finance in a lively and lucid way. And yes, Harris inspired me to make two $25 Kiva.org loans, one to an enterprising yogurt-maker in Pakistan and the other to a group of merchants in Bolivia.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in April 2013, and has been updated for the

March 2014 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in April 2013, and has been updated for the

March 2014 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked The International Bank of Bob, try these:

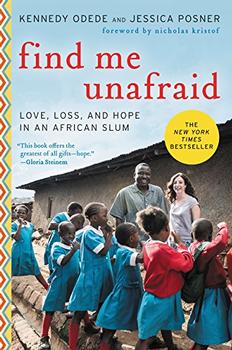

by Kennedy Odede, Jessica Posner

Published 2016

Find Me Unafraid tells the uncommon love story between two uncommon people whose collaboration sparked a successful movement to transform the lives of vulnerable girls and the urban poor. With a Foreword by Nicholas Kristof.

by Alison Thompson

Published 2011

The Third Wave tells the inspiring story of how volunteering changed Thompson’s life, and provides an invaluable inside glimpse into what really happens on the ground after a disaster—and a road map for what anyone can do to help.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.