Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Young Girl's Account of Life in a Concentration Camp

by Helga WeissIn 2011, Neil Bermel, translator of Helga's Diary: A Young Girl's Account of Life in a Concentration Camp, asked Helga Weiss, "What would you say is the contribution of your diary? Why should we read another account of the Holocaust?"

Helga answered, "Mostly because it is truthful."

That is at the heart of this significant and moving contribution to the literature of the Holocaust. Helga was 12 years old in 1941 when she was transported to Terezin and 15 ½ when she was liberated from Mauthausen, so the diary reflects the feelings, insights, and experiences of a young girl approaching womanhood, which is complicated and confusing in an ordinary setting, but which is unimaginably difficult in a concentration camp. Helga herself says, "…maybe because it's narrated in that half-childish way, it's accessible and expressive..." Helga's "childish" style gives a particular credibility and poignancy to the story she tells, and that credibility is important today when the Holocaust itself is being called into question at some of the highest levels of political and educational institutions such as Northwestern University professor Arthur Butz who wrote a book that denies the existence of the Holocaust. (See Beyond the Book.)

That is at the heart of this significant and moving contribution to the literature of the Holocaust. Helga was 12 years old in 1941 when she was transported to Terezin and 15 ½ when she was liberated from Mauthausen, so the diary reflects the feelings, insights, and experiences of a young girl approaching womanhood, which is complicated and confusing in an ordinary setting, but which is unimaginably difficult in a concentration camp. Helga herself says, "…maybe because it's narrated in that half-childish way, it's accessible and expressive..." Helga's "childish" style gives a particular credibility and poignancy to the story she tells, and that credibility is important today when the Holocaust itself is being called into question at some of the highest levels of political and educational institutions such as Northwestern University professor Arthur Butz who wrote a book that denies the existence of the Holocaust. (See Beyond the Book.)

Helga wrote some of her diary in real time - just before she entered Terezin and while she was there. (She brought two small dolls, watercolors, crayons and a pad of paper.) Just before she was transferred to Auschwitz, she was able to get her diary to her Uncle, who hid it in a brick wall. She retrieved it when she was finally liberated and wrote and rewrote the rest of the diary from her vivid memory. Helga's writing doesn't develop the philosophical and universal reflections we've come to expect in memoirs from the Holocaust such as those by Elie Wiesel, Etty Hil-lesum, and Anne Frank, but it records in a forthright and transparent way what Helga experienced, her responses to those experiences, and the experiences of the people she met – all living through this watershed in history as unique human persons.

Numbers can numb us to the truth: 20 million Russians died in World War II. 20 million more died in Stalin's gulags. 11 million Europeans died in Hitler's Holocaust, including 6 million Jews, fully two out of every three Jews in Europe at the time. We are not really able to comprehend numbers like these in any tangible way, and, in the case of the Holocaust, this is not only deceptive but also dangerous. Each person who perished or suffered through the horrors that we've come to know as Holocaust or, in Hebrew, The Shoah, are our family. The Shoah is the sum of millions of unique lives and personal experience. Only compassion can help us enter the single life of Helga Weiss, know her as our sister, and share her suffering.

The heart of Helga's Diary is Helga's determination to endure and to survive: Early on, when she is writing at Terezin, she says, "No one ever died from lack of a cinema or theater. You can live in overcrowded hostels... on bunks with flees and bedbugs...[or] without food, but even a bit of hunger can be tolerated...They want to destroy us, that's obvious, but we won't give in. We'll hold out..." Later, in Auschwitz: "We were no longer living off that quart of water and slice of bread... Now we live off the strength of our will. And we will survive!" This sense of purpose, even within such suffering, is what grounds Helga's life and what, eventually, leads to her survival.

Another survivor of Auschwitz, psychoanalyst Viktor Frankl, wrote in Man's Search for Meaning, "The way in which [one] accepts...fate and all the suffering it entails...gives ample opportunity – even under the most difficult circumstances – to add a deeper meaning to [one's] life. I became acquainted with those martyrs whose behavior in camp, whose suffering and death, bore witness to the fact the last inner freedom can't be lost. [Such a person] knows the why for [their] existence, and will be able to bear almost any how." Helga intuited that her suffering had meaning, even simply withstanding cold and hunger to remain with her mother; this carried her through all the hows she endured.

Though Helga may have seen too much raw evil to be able to feel, as Anne Frank does, that "despite everything, I believe that people are really good at heart," she still appreciates the small acts of kindness she witnesses and receives; she sees suffering prisoners care for a newborn and receives extra bread from someone who can ill afford to lose it. She also sees beauty in the natural world through all the ugliness and cruelty that surround her – on her way to the death camp Mauthausen, finding herself in the open air, she writes: "The setting sun leans into our backs and the fresh green grass ripples in a light breeze. A beetle crosses the path and a bit further along a butterfly settles on a flower. I never knew how much I loved this world." The future artist already finds her salvation in nature's healing loveliness.

Helga Weiss is now in her 80s; her book is a lasting gift to the world. Through her story, she reveals unmitigated suffering and gives us hope that in such circumstances, as Faulkner said, "…[we] will not merely endure; [we] will prevail." Though Helga never expresses finding meaning in her suffering, her own endurance points to her commitment to live in order to bring beauty to the world, which she did as an artist and art teacher through the rest of her life. Helga's Diary is, in fact, illustrated throughout with drawings that Helga created as a child, the seeds of her artistic profession planted in troubled soil, but growing all the same. Frankl says about his own survival, "Ultimately, [we] should not ask what the meaning of [our] life is, but rather [we] must recognize that it is [we] who [are] asked… Each [of us] is questioned by life; and [we] can only answer to life by answering for [our] own life." At each point of her life, both during the horrors of the Shoah and in the rest of her life, Helga said Yes to each moment - and thus created her own meaning. In this she conquered those who attempted to crush her.

Helga Weiss is now in her 80s; her book is a lasting gift to the world. Through her story, she reveals unmitigated suffering and gives us hope that in such circumstances, as Faulkner said, "…[we] will not merely endure; [we] will prevail." Though Helga never expresses finding meaning in her suffering, her own endurance points to her commitment to live in order to bring beauty to the world, which she did as an artist and art teacher through the rest of her life. Helga's Diary is, in fact, illustrated throughout with drawings that Helga created as a child, the seeds of her artistic profession planted in troubled soil, but growing all the same. Frankl says about his own survival, "Ultimately, [we] should not ask what the meaning of [our] life is, but rather [we] must recognize that it is [we] who [are] asked… Each [of us] is questioned by life; and [we] can only answer to life by answering for [our] own life." At each point of her life, both during the horrors of the Shoah and in the rest of her life, Helga said Yes to each moment - and thus created her own meaning. In this she conquered those who attempted to crush her.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in May 2013, and has been updated for the

February 2014 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in May 2013, and has been updated for the

February 2014 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked Helga's Diary, try these:

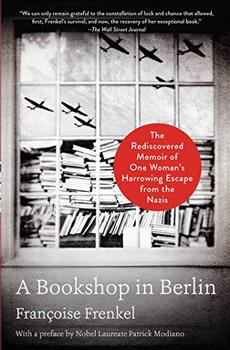

by Francoise Frenkel

Published 2020

"A beautiful and important book" (The Independent) in the tradition of rediscovered works like Suite Française and The Nazi Officer's Wife, the prize-winning memoir of a fearless Jewish bookseller on a harrowing fight for survival across Nazi-occupied Europe.

by Dawn Anahid MacKeen

Published 2017

An epic tale of one man's courage in the face of genocide and his granddaughter's quest to tell his story.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.