Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Patricia Storace's prose in The Book of Heaven is like a tinkling wind chime in a slight breeze. Like the flutter of butterfly wings that stir the fragrance of a coneflower, she writes lightly but with depth of thought that begs you to linger, ponder. Her creation of the heavens, designed with brand new cosmic constellations, (wo)manned by females who offer a look at the distaff side of the universe, may not be to everyone's taste - no book can suit everyone. But this is a must-read for its beautiful prose and for the opportunity to stop and ponder what the world might be like if viewed through the eyes of an "other." Specifically, with these stories - most Biblical in origin, of Eve (who narrates); Abraham's wife Sarah; the Queen of Sheba; Job's wife; and "Savour" a cook - we feel the weight of their responsibilities, their obligations within a culture they have not created.

Storace begins by explaining that our vision of Heaven and the stars exists as it does only because we have not wanted to see, or have not been shown, the wondrousness of an infinity of other heavens, even more constellations of stars. "The sky we have inherited is a sort of attic of the imagination...It is peopled with the violent and the anguished, warriors, archers, and weeping women." It's Eve who is taken on the back of a wingless bird to see the new constellations - gaining knowledge, memory, death and love from each, in kind.

And thus the short stories unfold. First is the story of Souraya (based on Abraham's wife, Sarah) who marries the ruggedly handsome Adon whose, "features were set on the scaffolding of his bone as if riveted there, they expressed a force that seemed almost metallic." Wow. Take that description in. Think about this man. Souraya soon realizes that the only power she might have "would only be through exaggerated, even competitive, obedience to the laws of her husband's God." Her life is a bitter one of betrayal and loss. First her husband sells her to a potential enemy to protect himself from the enemy's attack, and later she loses her son.

I am not a Biblical scholar, nor do I think it's necessary to be one to enjoy The Book of Heaven. As with any magical fiction, Storace takes liberal poetic license with these historical women's stories. The original tales were written by men; told from their perspective. Storace has clearly pondered these women's lives and experiences and has arrived at these different allegories; told from their perspectives. As a woman it is not all that difficult for me to give myself - and my disbelief - over to the author and identify with her point of view. It would be interesting to get a male perspective. But beyond gender, each story offers the opportunity to step beyond current beliefs into another realm of reality.

Next is the tale of "The Cauldron." Here, Savour is a cook of such talent that she is spared death in order to serve royalty. But she is spared only so long as what she cooks pleases them and their guests. As a wonderful cook Savour, "transfigures death, and exalts the act of eating. Those who eat and drink at such a supper encounter on their plates a meditation, a prayer, a remembrance; set before them as embodied pardon." The cook's gift is to transform death - of a beast - into life-giving nourishment. "Death," Storace writes, "passes through the hands of the cook, and becomes not destruction, but destiny." See what I mean? Lines like these are things that make you go, hmm, as well as mmm. There is so much about this allegory that brings to my mind the Biblical Mary who, according to Catholic dogma "was assumed body and soul into heavenly glory." The analogy to Mary is not explicit or even complete, but that's part of the beauty of being able to get lost in Storace's prose. Additionally, because of the overriding theme of Biblical women this interpretation was not a very big leap. The subsequent two chapters feature one story about death and one about love.

Storace writes in the same language as me and yet she uses it so much better than I. There are sentences, whole paragraphs here that take my breath away; that turn my brain around on itself in the best possible way, giving me brand new perspectives to taste, to savor, to remember. As I said, The Book of Heaven is not one for every reader, particularly those who eschew magical thinking and allegory. But in this reader's opinion the real reason to read it is for its writing. While the stories are fine, Storace's prose is greater than the whole.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in March 2014, and has been updated for the

November 2014 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in March 2014, and has been updated for the

November 2014 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked The Book of Heaven, try these:

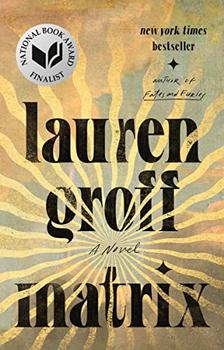

by Lauren Groff

Published 2022

Cast out of the royal court by Eleanor of Aquitaine, deemed too coarse and rough-hewn for marriage or courtly life, seventeen-year-old Marie de France is sent to England to be the new prioress of an impoverished abbey, its nuns on the brink of starvation and beset by disease.

by Sue Monk Kidd

Published 2021

An extraordinary story set in the first century about a woman who finds her voice and her destiny, from the celebrated number one New York Times bestselling author of The Secret Life of Bees and The Invention of Wings.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.