Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Discuss | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Winner of the 2015 BookBrowse Non-Fiction Award

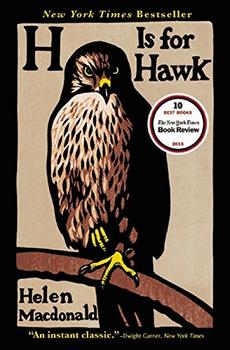

It is difficult to categorize Helen Macdonald's debut, H Is for Hawk; it is simultaneously a natural history, a literary biography, a memoir, and a chronicle of bereavement. It's also a thoughtful inquiry into the — often imagined or imaginary — relationship between people and wild animals and an intriguing glimpse into a world many of us probably didn't even know existed.

If your knowledge of falconry is limited to images from medieval romances, you will no doubt be fascinated to discover that a subculture of falconry is alive and well all over the world. Most present-day falconers use their birds for hunting small game, but it seems that others use them as an unusual way to interact with the wild, or to keep the dying sport alive. When Helen Macdonald, an historian and academic lecturer at Cambridge University, learns of the sudden death of her father, a photojournalist, she is driven by her grief to immerse herself in the great pastime and passion of her youth. This time, however, Macdonald is not drawn to the smaller and more manageable hawks or falcons; instead, she is determined to train and hunt with a goshawk, birds she had previously thought of as "things of death and difficulty: spooky, pale-eyed psychopaths that lived and killed in woodland thickets."

But as she grows inexplicably intent on obtaining and training a goshawk, she turns again to one of the books that shaped her understanding of the responsibilities of the falconer: The Goshawk by T. H. White. White, most famous for writing the modern Arthurian adaptation The Once and Future King, memorably turned young Arthur into a hawk as part of his fictional education under the tutelage of the wizard Merlyn.

But White himself was also an amateur falconer (or, more properly, an austringer, a keeper of goshawks). His account of trying — and largely failing — to train a goshawk proves both instructive and maddening to Macdonald as she embarks on the process of training a young goshawk named Mabel. As she struggles to understand what motivated White — and where he fell short of his own ambitions — Macdonald also eventually strives to understand the complex blend of emotions that has caused her to throw herself headlong into this renewed passion, at times at the expense of her human relationships and, when she essentially abandons her career in favor of time with her hawk, even her livelihood.

Some readers may be perplexed by the technical jargon such as "bating," "mutes," and "jesses," detailed accounts of Mabel's training with which Macdonald peppers her memoir. Regardless, her story is worthwhile reading for anyone who harbors more than a passing fancy for nature or who longs to understand the often inexplicable journey of grief. Macdonald is, in her fearlessly honest portrayal of herself, not always likeable or admirable; nonetheless, she eventually comes to see her own motivations with (dare I say?) eagle-eyed clarity.

Macdonald's relationship with Mabel helps her grieve, initially allowing Macdonald to pretend she is not human and therefore not subject to human emotions. As she comes to spend more time with Mabel, though, she realizes that humans' experience of loss — and their ability to reflect on it — is far more complicated than that of the hawk, which is really a plain and simple instrument of death.

Macdonald shies away from easy metaphors — when she is tempted simply to equate herself and her desire for invisibility with the hawk, to anthropomorphize Mabel or to conflate their experiences as they grow into a unified hunting team. In the end, Macdonald — as she begins to emerge from the grief that has almost consumed her — is able to reflect on larger questions, such as how and why we imbue wild creatures with human qualities and whose version of "nature" is worth preserving. Most of all, she realizes that — her genuine and hard-won affection for Mabel notwithstanding — she needs more than a raptor counterpart to find herself truly human: "Hands are for other human hands to hold. They should not be reserved exclusively as perches for hawks. And the wild is not a panacea for the human soul; too much in the air can corrode it to nothing."

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in March 2015, and has been updated for the

March 2016 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in March 2015, and has been updated for the

March 2016 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked H Is for Hawk, try these:

by Carys Davies

Published 2025

A stunning, exquisite novel from an award-winning writer about a minister dispatched to a remote island off of Scotland to "clear" the last remaining inhabitant, who has no intention of leaving—an unforgettable tale of resilience, change, and hope.

by Chloe Dalton

Published 2025

A moving and fascinating meditation on freedom, trust, loss, and our relationship with the natural world, explored through the story of one woman's unlikely friendship with a wild hare.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.