Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The Untold Story of World War Two's Greatest Escape

by Mark FeltonIn Zero Night, British military historian Mark Felton relays the story of the Warburg Wire Job, one of the more ingenious and daring prisoner-of-war escapes that took place during World War II.

Close to 3,000 Commonwealth officers were incarcerated in Oflag VI-B, a POW camp in northwestern Germany in 1941-1942, the time period covered in Zero Night. Tom Stallard, whom the author calls "one of the most determined escape artists in German captivity," was one of these, arriving in late 1941.

Quickly realizing that the German soldiers were more adept at discovering tunnels than the prisoners were at digging them, Stallard began considering less orthodox means of breaking out, landing on the novel idea of going over the fence instead of under or through it. Stallard spearheaded a secret committee, that during the next several months, developed a plan which came to fruition on the night of August 30, 1942 as he led 36 men over the two barbed wire barriers surrounding the camp.

Felton's fascinating and meticulously researched book covers not only the genesis of the escape plot but the creativity required to implement it; serendipitous events that contributed to its success; and the men's flight after leaving the camp. One of the more striking elements was that far more people planned and implemented the details than actually went over the wire. Jock Hamilton-Baillie, referred to as "the camp brain" and who designed the elaborate ladder mechanisms used in the breakout, was unable to take advantage of his invention; wounded earlier in the war, he knew from the outset that he wouldn't have the agility needed to participate.

Prisoners used their pre-war specialties to contribute to the effort; for example those skilled in cartography created copies of contraband maps (using an "ink" made in part from grape jelly) and officers who had been electricians undertook the daring job of sabotaging the perimeter lights. A few served as lookouts, staking out the sentries to determine their optimum positions before signaling the start of operations, while still others created a diversion. Perhaps the most dangerous role was undertaken by volunteers who, working in pairs, steadied the ladders for the escapees. They were directly in the guards' line of fire and consequently at as much risk as those leaving, but would stay behind and hopefully disappear back into the barracks to avoid being caught.

Some readers might have concerns about reading a nonfiction book that take place in prison camps because conditions in them were often brutal. Felton notes the difficulties of being a POW at Oflag VI-B:

The prisoners soon discovered that Warburg was almost unfit for human habitation. Mice and rats scampered around underneath the bunks at night, or ran across the sleeping forms of the prisoners, leaving their droppings everywhere. The vermin in turn carried fleas and added to the lice that already infested the prisoners' uniforms and sleeping quarters...Meals in October 1941 consisted of hot vegetable soup only once a day with a meagre issue of bread, margarine and jam, amounting to only about 1,000 calories. Fortunately Red Cross parcels were available in large quantities; without these the prisoners would have started dying of starvation…Sickness spread quickly among the POWs, packed like sardines inside filthy huts. The Germans provided an infirmary with 84 beds and this was filled to capacity between October and December 1941.

The author limits this type of commentary to just a few pages, however, and it's a far cry from the prison-camp horrors reported in books like Unbroken or The Narrow Road to the Deep North. Granted, Germany treated its Allied POWs (particularly officers) much better than Japan did, but hardships were ongoing and atrocities against prisoners certainly occurred. Felton soft-peddles the adversity and privation, putting them well in the background and choosing to emphasize the action-adventure aspect of the planning and execution of the escape.

The book contains a fair amount of dialog, which I always find suspect in a work relaying events occurring many years in the past. Felton states, "Most of the dialogue sequences in this book come directly from the veterans themselves, from written sources, diaries or spoken interviews. I have changed the tense to make it more immediate. Occasionally, where only basic descriptions of what happened exist, I have created small sections of dialogue, attempting to remain true to the characters and to their manners of speech." Even with this in mind, however, I felt like the author took liberties in creating conversational scenes, which detracted from the book's overall impact as a work of nonfiction. It was also overly repetitive; sometimes repeating facts is necessary in a longer narrative, but the items the author chose to reiterate were distinctive and didn't need to be restated. And finally, I wanted more of an ending. The author includes a few sentences about what became of many of the key players after the escape, but I would have liked the narrative to continue beyond where the story ends.

Overall Zero Night is engaging and entertaining, and anyone with an interest in WWII will find it worth their while. Felton's account is utterly absorbing and is sure to find a wide audience.

![]() This review

first ran in the September 2, 2015

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This review

first ran in the September 2, 2015

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

If you liked Zero Night, try these:

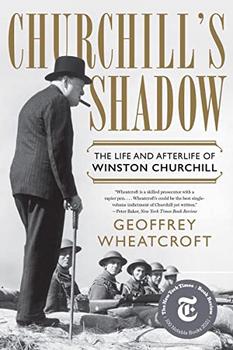

by Geoffrey Wheatcroft

Published 2023

A major reassessment of Winston Churchill that examines his lasting influence in politics and culture.

The Narrow Road to the Deep North

by Richard Flanagan

Published 2015

Moving deftly from a Japanese POW camp to contemporary Australia, this savagely beautiful novel tells a story of love, death, and family, exploring the many forms of good and evil, war and truth, guilt and transcendence.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.