Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Speak alternates between six different narratives, ranging from a seventeenth-century diary to the lament of a robot discarded in the desert in the near future. That Louisa Hall manages to link such diverse stories is a testament to her skills in plotting and creating authentic voices. Like David Mitchell (Cloud Atlas et al.), Sara Taylor (The Shore), and Susan Barker (The Incarnations), Hall draws unexpected connections across centuries and between characters to convey a broader meaning. Here, as the title suggests, the central message is about the difficulty of true communication.

The novel opens with a list of the human voices readers will encounter, yet the first narrator we hear from is a robot. She and her fellow machines are being driven across the Texas desert and dumped in an old air force hangar, the relics of an experiment gone bad. Next we hear from Stephen R. Chinn, a disgraced scientist composing his memoirs from a Texas prison in the year 2040. He was responsible for designing these "babybots," artificial intelligence dolls that learned from their owners through conversations and scored 90% on a Turing Test (see 'Beyond the Book'). Through his own daughter's relationship with her robot, Chinn witnessed how this exclusive human–machine friendship could replace the outside world.

The remaining voices fill in gaps in the development of artificial intelligence and show what went wrong with Chinn's bots. Karl Dettman's 1960s letters to his estranged wife, Ruth, document how they created the first MARY robot. Meanwhile, the record of an online chat between a young woman, Gaby White and a third-generation MARY robot reveals Gaby's pain at being separated from her bot and the sickness now attacking women like her: they are "freezing," gradually losing their senses, movement, and speech. Retreating further into history, we also hear from Alan Turing, an early student of the mechanical brain, via letters to his best friend's mother; and from thirteen-year-old Mary Bradford, the MARY robot's namesake, whose seventeenth-century diary of a transatlantic crossing was what Ruth used as the basis to program the machine's speech.

The fact that all these narratives are in different documentary formats – memoirs, letters, the transcript of a dialogue, and a diary – and headed with a date and name means they are easy to distinguish. Moreover, the voices themselves are very different in tone: Chinn is wryly apologetic for his past mistakes, including his marital indiscretions; Mary is naively eager for the adventure of moving from England to Massachusetts; over the decades, Turing vacillates between intellectual vigor and resignation; and so on.

Still, there are strong elements linking all the characters. They have each lost someone important, and to some extent the idea of artificial intelligence – creating a perfect companion – is an attempt to make up for an irrecoverable loss. This cacophony of voices, some monologues and some dialogues, is Hall's collective comment on the difficulty of sustaining intimate communication. Each character, even the robot, realizes language is precious. Mary's betrothed, Roger Whittier, calls speech "a sacred gift...a sign of connection with God and the truest expression of human affection." However, it's also fragile, as the decommissioned robots and the frozen girls learn. Language can be lost, and communication can cease through choice or natural decay. As Karl Dettman writes bitterly to Ruth, "What's a marriage but a long conversation, and you've chosen to converse only with MARY."

One might argue that two of the narratives – Turing's letters and Mary's shipboard diary – are unnecessary, and yet these were by far the two most enjoyable voices for me. They prove that Hall has an aptitude for historical fiction, a genre she might choose to pursue in the future. Would cutting those two storylines have made the whole novel tighter and more focused on the saga of the MARY robots? It's hard to say. The connections between the stories are uncovered so early on that there aren't many thrilling revelations to stick around for, which means Speak can feel overlong at times.

All the same, Hall has written a remarkable book interrogating how the languages we converse in and the stories we tell make us human. "We speak, but there is little evidence of real comprehension," one robot says – a distinction that could just as easily be applied to the human misunderstandings that pervade Speak. Artificial intelligence will only advance in the coming years, and this impressive novel will help readers think through the advantages it offers alongside the threats it poses.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in September 2015, and has been updated for the

May 2016 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in September 2015, and has been updated for the

May 2016 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked Speak, try these:

by Jayson Greene

Published 2025

From the author of Once More We Saw Stars comes a gripping novel about four intertwined lives that collide in the wake of a mysterious tragedy. Set in a near-future world where the boundaries between human and AI blur, the story challenges our understanding of consciousness and humanity.

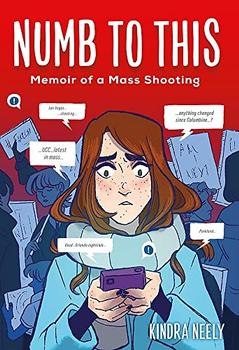

by Kindra Neely

Published 2022

This searing graphic memoir portrays the impact of gun violence through a fresh lens with urgency, humanity, and a very personal hope.

When you are growing up there are two institutional places that affect you most powerfully: the church, which ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.