Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Rarely do you encounter a literary character the likes of Milo Andret (rhymes with "silo bandit"). He is the academically underachieving Baby Boomer only child who spends the vast majority of his largely solitary youth more at home in the woods behind his Northern Michigan home than anywhere else. Anywhere. He knows where everything is there. Everything. He can hide the extraordinary things he whittles inside hollowed out tree trunks and locate them weeks, decades later. He can know – before laying eyes on it – when a fallen tree has disturbed the equanimity of the woods. This quality, quirky as it is, gives Milo a likeability, a sympathique, and a charm that is quite engaging. So I wanted to know more about him right from the start.

He muddles along academically – excelling in math but so-so in other subjects, and socially – getting routinely beaten up, making no real friends. And girls? Forget it. It isn't until graduate school at University of California, Berkeley that his particular, unique gift is given a name. He has positional aptitude:

[H]e'd long been able to picture the world, all of its six dimensions, his exact place in any three-dimensional topography…For as long as he could remember, his surroundings had been forming themselves into an inverted, low-sloping bowl, a hemisphere of smoothly shifting coordinates in which his position at the center was continually being recalibrated.

It is there at UC Berkeley that Milo's mentor, mathematics Professor Dr. Hans Borland, suggests the young man specialize in topology. The professor is completely gobsmacked by Milo's brilliance, bowling him over with praise; gushing even, to the point that, according to Borland, Milo has been cosmically called to the challenging specialty. "Topology is God's rules, Andret…And you've been called upon to translate them."

From his tiny basement apartment, a naïve Milo ventures into previously unexplored worlds of high mathematics, competition/ambition, friends, women and addictive substances. He takes on the challenge of proving a heretofore-unproven theorem and, bolstered by bourbon, becomes determined to win the mathematics equivalent of the Nobel Prize. Also bolstered by bourbon it becomes easier for him to socialize with and – in the spirit of the sixties – bed women. He soars! Eventually he wins the prize and a prime position at Princeton University. He is indomitable, egomaniacal and a full-blown addict. Of course the indomitable part doesn't last. It's the ego and addictions that undo him, ultimately crash-landing him at a midwestern women's college, a lowly and low-paying teaching position. He's married to a longsuffering woman he doesn't deserve. They have two children.

At this point, the narrative takes a hairpin turn. From here on, Milo's son takes over. Hans's first person narrative focuses on his and sister Paulette's youth spent with one parent a brilliant, egotistical, maladjusted addict and the other a hapless enabler. Like father, like son. Hans is an addict, but a failure in his father's eyes only because Hans has used his mathematical genius to a practical end. He's amassed a fortune in the hedge fund lunacy of the aughts. Hans is married – also to a woman he doesn't deserve. They have two children.

It is an oft-told story. The one about addiction and the dysfunction it visits upon families, crippling the children. Hans's sister Paulette nails it when she declines Hans's request to visit Milo: "It's like quicksand. I keep trying to push myself up, but the ground keeps sinking. That's him. He's the quicksand I grew up on."

What sets Canin's story apart from other dysfunctional family novels is the awesome writing, the mid-plot switch of narrator augmented by the juxtaposition of Milo's superhuman intelligence and his addiction. It is indicative of Canin's own genius that he makes all that – plus mathematics references that sent me to Google more than once – work superbly.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in February 2016, and has been updated for the

November 2016 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in February 2016, and has been updated for the

November 2016 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked A Doubter's Almanac, try these:

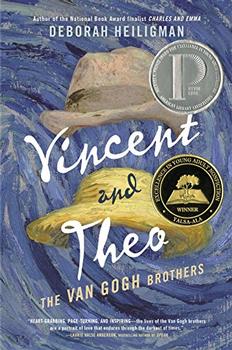

by Deborah Heiligman

Published 2019

From the author of National Book Award finalist Charles and Emma comes an incredible story of brotherly love.

by Ann Patchett

Published 2017

The acclaimed, bestselling author - winner of the PEN/Faulkner Award and the Orange Prize - tells the enthralling story of how an unexpected romantic encounter irrevocably changes two families' lives.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.