Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The philosopher Soren Kierkegaard once noted that "Life can only be understood backwards but it must be lived forwards." Anybody with a few decades under their belt can likely attest to the wisdom of that idea. Viewed this way, predilections are actually predictions, and the people we become, it turns out, were there all along. This must have seemed like a novel idea to Arturo Perez-Reverte, whose What We Become traces the arc of a suave jewel thief's life as it's glimpsed during three key episodes across four decades. Later, when he stops thieving long enough to reflect on what it all means, he understands – a little bit, anyway – the significance of his earlier times, where he went right, where he went wrong, and why he had such trouble telling the difference.

And of course – in a book about a charming, handsome international thief who masquerades as a professional tango dancer – the answer has to do with women. Or, in the case of Max Costa, the protagonist of this sprawling, picaresque novel, one particular woman:

As a professional, Max knew it was impossible to perform the tango without a skilled partner capable of following a dance whose flow would suddenly stop, the man slowing the rhythm, reenacting a struggle, in which, entwined around him, the woman would continually attempt to flee, only to yield each time, proud and defiant in her submission. Mecha Inzunza de Troeye proved to be that sort of partner.

At first merely a dance partner, Mecha later becomes involved with Max in the lifelong tango of memory, desire, and regret. The novel sways back and forth in time between the sultry decadence of Buenos Aires in 1928, the jitteriness of pre-war Nice in 1937, and finally in tourist-chic Sorrento in 1966. In each of the time frames, Max commits a different crime – though it's really the same one: being seduced into an action that eventually comes back to haunt him.

Perez-Reverte is a highly accomplished author whose books inhabit the chasm between genre and literary fiction. He can do breathless, but he can also do breadth. He provides plenty of adrenaline-fueled scenes but he also allows his characters time to reflect. And when any of the three episodes starts to lag, Perez-Reverte shifts the time frame, a handy tool to have in one's literary handbag. The author knows well the physical and psychic topography of each place he writes about – most strikingly Buenos Aires in the 1920s, teeming with peasants, high-rollers, con men, commerce, love, lust, music, and danger, "a chaotic, promiscuous place where any kind of privacy was unimaginable."

But for all the atmospheric brio and the splendid characterizations (Max, gazing in a mirror and "winking at himself in absolution, as though recognizing in that tall, no longer slim, old man with dark, weary eyes, the image of a former accomplice for whom any explanation is unnecessary..."), the novel ultimately fails to convey any genuine sense of pathos for the struggles of the characters, or the tragic compromises they've made. The reader eavesdrops on the conversations about how these two have longed for each other, and always loved each other, but that longing – the pain of separation and regret – is told, not shown. Too much seems to have happened to both characters to which the reader has not been privy, and when they meet over the decades in Buenos Aires, Nice, and Sorrento to compare notes, their pain seems genuine, but it's overheard – not experienced.

In previous works like The Siege and The Club Dumas, the poignancy and emotional devastation were a by-product of the tightly knit story, while in this book the emotional revelations feel like an adjunct to the plot, tacked on to give the derring-do of the almost 500 pages an emotional heft.

Within each of the time frames, there is intrigue aplenty. Jewel thieving in exotic and dangerous places among characters of the highest and lowest social stature offers an attractive palate for a writer of Perez-Reverte's gifts, and he makes the most of it. There are mobsters, spies, rich widows, foolhardy social climbers, and a real rogues gallery of small-time hoods and wannabe players. And at the end of all his adventuring, Max can look back on a life of tumult and deprivation, of grandeur and squalor, of love and loss, and understand finally what it all means. As for the reader, well, I guess we'll just have to take Max's word for it.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in August 2016, and has been updated for the

April 2017 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in August 2016, and has been updated for the

April 2017 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked What We Become, try these:

by Dean Jobb

Published 2026

In this captivating Jazz Age true crime about "the greatest jewel thief who ever lived" (Life Magazine), Arthur Barry, who charmed celebrities and millionaires while simultaneously planning and executing the most audacious and lucrative heists of the 1920s.

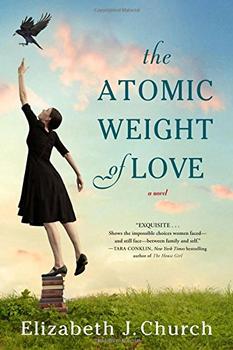

by Elizabeth Church

Published 2017

In the spirit of The Aviator's Wife and Loving Frank, this resonant debut spans the years from World War II through the Vietnam War to tell the story of a woman whose scientific ambition is caught up in her relationships with two very different men.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.