Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Discuss | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

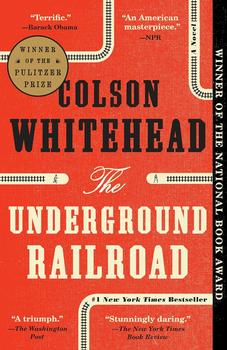

by Colson WhiteheadEven when he's writing about zombies (like in Zone One) or poker (like in The Noble Hustle), Colson Whitehead demonstrates stunning intellectual and linguistic dexterity, often making unexpected connections and bridging gaps which cause readers to look, with fresh eyes, at things they might have thought they already knew everything about. The buzz for his new novel, The Underground Railroad, was already intense after fans learned that it would be a sort of alternative history of slavery in America; a return to the kind of social observation and rich historical reimagining that first gained him critical acclaim in books like John Henry Days and The Intuitionist. And then Oprah Winfrey chose The Underground Railroad to relaunch her book club – and it's no exaggeration to say that Colson Whitehead's novel has become one of the most talked about books of the year.

The Underground Railroad centers on Cora, a third-generation slave on a Georgia cotton plantation. Cora's only possession (in a manner of speaking), the one thing in the world she prizes above all else, is a small patch of land that her grandmother and then her mother Mabel also guarded and defended, carving out a small garden plot and nurturing what grew there. The yams from the plot, Cora believes, nourished Mabel during her successful escape from the Randall plantation when Cora was just a small child.

As the novel opens, Cora, who is still a very young woman, is offered the opportunity to escape. Another slave, Caesar, has learned that a new spur of the underground railroad - in Whitehead's world it is an actual railroad with tracks and trains - has been extended as far south as Georgia. A sympathetic white man has offered to help Caesar escape, and he wants to bring Cora – the legendary Mabel's daughter – along "for luck." At first, Cora declines, but after conditions on the plantation continue to deteriorate, she reluctantly agrees to accompany Caesar, filling her bag – as her mother did before her – with every last vegetable from her plot.

What follows is a journey both harrowing and exhilarating, as Cora travels through South and North Carolina, and as far away as Tennessee and Indiana. In nearly every place, she experiences both kindness and betrayal, fragile hope and staggering loss – and, of course, danger at every turn, right up to the final page.

Whitehead's novel is the best kind of historical fiction, one that prompts the reader to draw vital connections between past and present. It is suffused with real, true history, the history of slavery and its aftermath, whose painful and horrific stories are essential for modern-day readers to continue to confront. But it also is an alternative history, one in which an entire state bans black people on penalty of death while its neighboring state affords (on the surface anyway) more egalitarian options. And, of course, there's the physical underground railroad itself, which is, in Whitehead's telling, running on unpredictable schedules and routes through tunnels built by mysterious hands. "Look outside as you speed through," the conductor tells Cora before she embarks on her first voyage, "and you'll find the true face of America." Is that "face" the varied landscapes and social experiments she finds herself traveling through, Cora wonders much later, or is it the pure darkness of the tunnel walls? That question is left up to readers to interpret, as are the novel's numerous reflections on the ugly truths of slavery, racial tensions, and nation-building, many of which still resonate today.

Near the end of the novel, one character offers Cora perhaps the most hopeful statement in the book, adopting the outlook that whites and blacks hold the keys to create and define their own future in this young, newly forming nation: "We are Africans in America," he tells her. "Something new in the history of the world, without models for what we will become…All I truly know is that we rise and fall as one, one colored family living next door to one white family. We may not know the way through the forest, but we can pick each other up when we fall, and we will arrive together." This ultimately optimistic vision for what America could become is, of course, palpably bittersweet for modern-day Americans to read. Reading The Underground Railroad offers plenty of reminders of just how far our nation has come since these darkest years in our history, but also countless reminders of just how far we have yet to travel before we arrive at any destination resembling that hopeful vision.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in September 2016, and has been updated for the

February 2018 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in September 2016, and has been updated for the

February 2018 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked The Underground Railroad, try these:

by Jesmyn Ward

Published 2024

From Jesmyn Ward—the two-time National Book Award winner, youngest winner of the Library of Congress Prize for Fiction, and MacArthur Fellow—comes a haunting masterpiece, sure to be an instant classic, about an enslaved girl in the years before the Civil War.

by Zadie Smith

Published 2024

From acclaimed and bestselling novelist Zadie Smith, a kaleidoscopic work of historical fiction set against the legal trial that divided Victorian England, about who gets to tell their story—and who gets to be believed

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.