Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

With almost all the accoutrements of upper middle-class suburban life, Julia and Jacob Bloch fit the very definition of a successful American family. They live in a tricked-up house in a tony D. C. suburb with their sons, Sam, Max, and Benjy, and aging dog Argus. The ground under their sixteen-year marriage has been shifting ever so gradually, but it takes one seismic event — Julia's detection of her husband sexting another woman — to truly shear their relationship. Scratch that veneer of storybook perfection and the warts slowly emerge.

There's the shaky marriage for sure, but an accident in the past in which Sam lost a few fingers also casts a dark shadow, creating "a black hole of silence from which everything had to keep a safe distance." Jacob's grandfather is slowly dying just as his great grandson, Sam, is about to celebrate his bar mitzvah, much against the boy's wishes. "The truth is I didn't want to have a bat mitzvah. No part of me, not even a little," Sam says, adopting an online persona, Samanta. "There aren't enough savings bonds in the world. We had conversations about it, with the pretense of the bat mitzvah being, ultimately, my choice. It was all a charade, a charade to set in motion this charade, itself only a stepping stone in the charade of my Jewish identity."

Jonathan Safran Foer, whose brilliant and imaginative work has invariably been built on some part of the Jewish American experience, really goes into overdrive here. Sam's upcoming passage of initiation allows Foer to dissect the definition of Jewish identity with a fine scalpel. This task is made even easier when, about a little more than a third of the way into the book, the Blochs are joined by their Israeli counterparts. Tamir gnaws on Jacob's vulnerabilities and manages to sow seeds of self-doubt in his cousin, who has already been wondering if he is Jewish enough or what really it means to be a Jew. To see it as Jacob would, a Jewish man seems to be riddled by the weight of generations of survivor guilt: He studies things he isn't interested in but are "good and worthy and remunerative," he gets married "Jewishly" and has Jewish kids and lives "Jewishly" in "some demented effort to redeem the suffering that made your increasingly alienating life possible."

As if these existential conundrums weren't enough to rock the foundations of Julia and Jacob's marriage, a colossal earthquake of a more literal variety (magnitude 7.6) hits the motherland and Israel is besieged — by her unfriendly neighbors and by circumstances even the ablest governments might find difficult to control. Foer is on his own shaky ground here, as he juxtaposes the Bloch family matters against the larger situation unfolding in the Middle East. These pendulum shifts — the Israeli Prime Minister imploring all Jewish men to return to the homeland and fight; the American Department of State issuing one formal statement after another, and the more mundane fights between various members of the Bloch family — are disorienting and far-fetched. It is difficult to see exactly where Foer is going with this. In trying to extrapolate the Blochs' challenges to a global Jewish commonality, he loses the reader on both counts.

Foer has always been known for his acrobatics in writing, playing with fonts and other media to convey tone and mood, for example, without distracting from storyline. There are no such pyrotechnics here, except for a long section towards the end where we're presented with a series of fuzzy "how-tos": HOW TO PLAY THE DEATH OF LANGUAGE; HOW TO PLAY NO ONE; HOW TO PLAY HOME. Instead, most noticeable is the biting and crisp dialog, which is initially bracing and witty, but deteriorates into too much long-windedness and self-absorption as page after page gets soaked up by passages like this:

"You said you've done your share of fantasizing. About what?"

"I don't know," she said, taking a drink. "I was just talking."

"I know. And I'm just asking. What do you fantasize about?"

"That's none of your business."

"Not of my business?"

"None."

"Drunk on your weakness?"

"I don't find you cute."

"OK."

"Or sexy. Despite all of the effort."

"I haven't made a single effort."

"Clearly."

And on and on it goes. Once Julia complains that Jacob is "always talking" and that "his words don't mean anything." One can see her point after a while.

I imagine that being a Jewish American (I am not), especially a Jewish American man who can relate to Jacob's existential crisis, might cast Here I Am in an infinitely more favorable light. But one of the responsibilities of good fiction is to make the story universal, to draw the reader in. Sadly, while there might be a couple of redeeming facets to this novel, the Blochs are too busy navel-gazing to really lend anybody else a helping hand.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in September 2016, and has been updated for the

June 2017 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in September 2016, and has been updated for the

June 2017 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked Here I Am, try these:

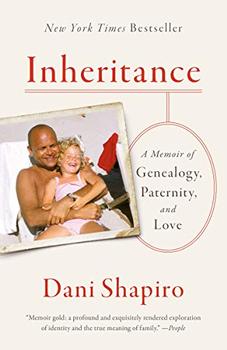

by Dani Shapiro

Published 2020

A new memoir about identity, paternity, and family secrets--a real-time exploration of the staggering discovery Shapiro recently made about her father, and her struggle to piece together the hidden story of her own life.

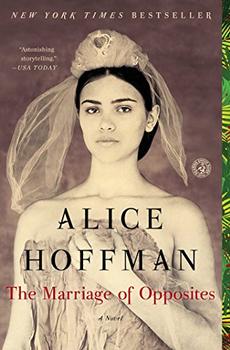

by Alice Hoffman

Published 2016

A forbidden love story set on the tropical island of St. Thomas, about the extraordinary woman who gave birth to painter Camille Pissarro - the Father of Impressionism.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.