Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

It's the Age of Enlightenment and it seems every man (and woman) in Europe is studying the stars. In England, musician William Herschel discovers a planet, while in Ireland, the eccentric Arthur Ainsworth seeks a planet of his own, and a respite from his grief. Herschel's and Ainsworth's astronomical pursuits notwithstanding, it's the women in their lives that drive the plot of the historical fiction novel, The Blind Astronomer's Daughter.

Arthur's daughter, Caroline Ainsworth, is an adopted orphan, rescued from a life of poverty in rural Instioge in Ireland. She is a bold and intelligent young woman, devoted to helping her increasingly blind and mentally unstable father with his study of the stars. When the Ainsworths hire a blacksmith's son, Finnegan O'Siodha, to help build a spectacular telescope, the two young people are overcome by their powerful feelings for one another.

On a parallel track, William Herschel brings his sister, another Caroline, from their native Hanover to Bath, England, where they teach music lessons and study binary stars—systems of double stars with a shared orbit (see 'Beyond the Book'). William is appointed King George III's court astronomer and Caroline is an expert in her own right with a singular devotion to the sky.

The Herschels' many discoveries, not to mention the construction of their own massive telescope, fuels a one-sided rivalry in Arthur Ainsworth who views William Herschel as the bane of his existence. When word of Herschel's discovery of "Georgium sidus" (the Georgian planet, later labeled as Uranus) reaches Ireland, Ainsworth becomes obsessed with finding a planet of his own. In the Ainsworth household, circumstances force Caroline and Finn to separate; Finn flees to Scotland where he becomes a crafter of medical devices for the limbless and otherwise impaired, while Caroline establishes herself in England, doing computations for yet more stargazers. When they both return to Instioge and it seems they'll finally be united, the Irish Rebellion comes tearing through the countryside and they must scatter and reconstruct their lives all over again.

Pipkin finds ample ground for metaphor in celestial principles, particularly gravitational pull, noting that "a solitary body will forever attract another to itself." The Herschels, Ainsworths, and Finn O'Siodha, with their chance connections and shared preoccupations, drift in and out of each others' lives, orbiting like satellites over the span of nearly 80 years. However, the analogy is made so many times, in nearly identical language, that it becomes worn with overuse. Finn and Caroline circle each other in the observatory "like two distant planets" and, just a few pages later, as Caroline observes Finn from her window, we are reminded that "solitary objects separated by inconceivable distances pull at each other."

Pipkin stays a bit too long with Arthur Ainsworth, elaborating his entire history of misfortunes and motivations, when this character turns out to be secondary in the scope of the overall narrative. The two Carolines share not only a name, but a similar disposition. Both have scars, figurative and literal, and both possess the fortitude and single-mindedness that make scientific discovery possible.

The plot takes a while to get up and running, and even when it does, proceeds slowly. To be fair, it takes time to construct a story that is as big as the heavens. While there are definite breaks in the action, the competition between the Ainsworths and the Herschels to construct a bigger and better telescope, one-sided though it may be, provides some Cold War-level tension, and when Finn finds himself entangled in the Irish Rebellion, Pipkin provides a few rousing battle scenes. The novel judiciously avoids sentimentalizing the rebels, making the wider point that, however righteous the cause, political uprisings often sweep innocent bystanders into a violent maelstrom.

The scope of The Blind Astronomer's Daughter may be a bit too big, its cast a bit too populous, but the final chapters redeem these minor flaws. The characters do not end up where one might predict but the creative novelty in the final alignment of people and events is satisfying all the same.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in November 2016, and has been updated for the

September 2017 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in November 2016, and has been updated for the

September 2017 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked The Blind Astronomer's Daughter, try these:

by Sarah Perry

Published 2025

A dazzling new work of literary fiction from the author of The Essex Serpent, a story of love and astronomy told over the course of twenty years through the lives of two improbable best friends.

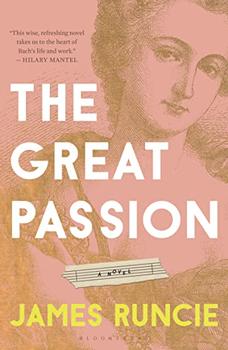

by James Runcie

Published 2023

From acclaimed bestselling author James Runcie, a meditation on grief and music, told through the story of Bach's writing of the St. Matthew Passion.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.