Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

In his ninth decade, the prolific and celebrated Hoagland meditates on blindness and how disability can warp human connection in his latest literary fiction, In the Country of the Blind.

The story's set in Vermont, but it is more a novel of character than place. The protagonist, Press, lives on Ten Mile Road in a rural area in the northern most reaches of Vermont, almost Canada, a place where the near-blind Press perceives his environment as "ninepin thunder, pelting rain, a coon in the garbage can, loose slats rattling somewhere in the wind ..." Press had worked for Merrill-Lynch, accumulating enough money to retire to his woodland cabin while still supporting his ex-wife, Claire, and their two children, Molly and Jeremy. Press believes his marriage failed as his vision deteriorated. One friend remarked that Claire "had kicked him out for going blind." That's a bold statement, one Press seems to accept with an unrealistic sense of equanimity.

Hoagland's spot-on in his characterizations of rural folk in his tale. Neighbors are the Clarks, evangelical Christians who welcome Press into their home with kindness in spite of his blasé attitude toward things spiritual. Other neighbors are the Swinnertons, the husband is a decorated war hero descended from bootleggers, and his wife is always ready to mother Press. Practical advice and local gossip come from outlier Melba, a rough-hewn, well-traveled woman who spent her youth chasing cowboys on the rodeo circuit out west.

The nicely paced narrative threads are subtle and symbolic, each laced with distinctive descriptions and natural dialog. Hoagland deftly explores loss of sight from an individual point of view. Press occupies a readily navigable environment, but even so, he is isolated from the wider world. Nevertheless, in Vermont, Press finds less overt pity. He's accepted into local society as much as any outsider, an attitude ironically mimicked by hippies in a local commune, outsiders themselves. It is another neighbor, Carol, a sometime hippie living on the edge of the commune who "offered muffin-gentleness, pragmatic, yet religion-tinged." Press is attracted to her, but Hoagland's nuanced portrayal of Carol shows a woman who likes Press and needs material things from him, things that she takes reluctantly; a woman who borders her selfishness with certain ethical boundaries. Carol also teases him with hints of a sexual relationship, something that never extends beyond erotic touching, and she refuses to commit to a love affair, telling Press she has herpes. It's a vague, one-sided romance, with Carol sometimes mooning over a married man in another community, while Press pants after her with puppy-dog anticipation, an attraction that's perhaps an attempt at a subconscious reinforcement of his masculinity. Hoagland handles this almost-romance between the damaged, neurotic Carol and the near-blind, needy Press with assurance.

It's Carol's introduction of Press to the commune that provides the catalyst for the narrative. There's marijuana, of course, and with Press's house being astraddle of an old Prohibition-era smuggler's path from Canada to the U.S., he's suspected by local authorities not of smuggling, but rather of providing storage for, marijuana. (See Beyond the Book.) There are other allusions to Prohibition – remember the Swinnerton ancestors were bootleggers – and there is Chuck, a drifter who makes runs for the commune to nearby cities, who accepts Press as someone other than an almost-blind man. He convinces Press to go south with him for the winter, a trip which provides the unexpected, post-modern conclusion of the novel.

It's no great leap to understand that people with disabilities are people, subject to all the emotional foibles and prejudices of every other human, an element which Hoagland sketches perfectly. It's Press's lack of anger with his wife that jars, that puzzles, that comes across as too good to be true. More realistic is Press's interaction with long-time friends when he visits his former home in Connecticut. Press is met with suggestions that he return and join an assisted living community, a typical patronizing attitude when well-meaning people approach those with disabilities. Nevertheless, Press's subconscious rejection of disability, the isolation, the will not to be perceived as a "handicap" worthy of special "empathy" all ring true.

Hoagland's fans will want to read In the Country of the Blind; for one thing, it is perhaps the nearest he will come to confronting his own deteriorating eyesight. His protagonist's reaction to loss of vision is nuanced and carries the weight of worldly experience, making for an intensely personal, almost elegiac, novel.

![]() This review

first ran in the November 16, 2016

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This review

first ran in the November 16, 2016

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

If you liked In the Country of the Blind, try these:

by Andrew Leland

Published 2024

A witty, winning, and revelatory personal narrative of the author's transition from sightedness to blindness and his quest to learn about blindness as a rich culture all its own

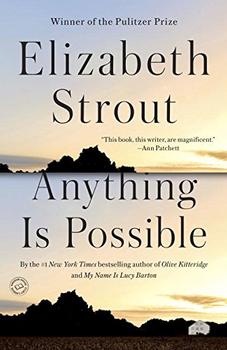

by Elizabeth Strout

Published 2018

An unforgettable cast of small-town characters copes with love and loss in this new work of fiction by #1 bestselling author and Pulitzer Prize winner Elizabeth Strout.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.