Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Margery Williams Bianco was the author of one of the world's best-loved, classic children's books, The Velveteen Rabbit. Her daughter, Pamela Bianco, became a famous artist when she was still a child, with her first gallery showing in Turin, Italy when she was only 11. However, child prodigies (see Beyond the Book) cannot remain young forever, and when they grow up they are often forgotten. Such is the case with Pamela Bianco; most people don't know anything about her. In her fictional account of their lives, The Velveteen Daughter, Laurel Davis Huber delves into the relationship between Pamela and her mother, while positing what caused her to fall into relative obscurity.

I should admit that I never read The Velveteen Rabbit as a child. However, Huber includes the full text in her novel, so it filled that gaping hole in my education. However, Huber does much more than that. She tells this story through alternating, first-person accounts from the two protagonists, Margery and Pamela; semi-memoirs from both, which describe the pain and joys that they experienced and witnessed in each other as Pamela grew up. This is, perhaps, more a story about a mother-daughter relationship than about either woman in particular, although the spotlight is stronger on Pamela.

Utilizing this dual narrative structure, along with a conversational style of prose, and some tangents into the poetic when emotions run high, the story moves us from Pamela's youth, to Margery meeting her husband, to Pamela as an older woman, and back again. A slew of minor characters make appearances, most of whom were actual personalities in these women's lives, including the playwright Eugene O'Neil and artist Pablo Picasso. However, the most significant character is the Welsh writer Richard Hughes, who called himself Diccon. Huber seems to suggest that some of Pamela's depression was due to the unrequited love she felt for Diccon and her feeling of betrayal when he fell in love with another woman. This event, coming at the same time as Pamela just reaching young adulthood, makes for a plausible reason for her mental deterioration.

Through these women's stories, we get a portrait of depression both from the viewpoint of the sufferer and the viewpoint of the close, if not heavily involved, observer. Of course, depression is a complicated disease, and Huber suggests other things besides the childhood love that never grew into a romantic relationship, which also might have contributed to Pamela's instability. These include the loss of a feeling of family, pressure about money and the need to produce more artwork to solve that financial problem, the feelings that she's disappointing the people she loves, as well as her father's bouts of depression as a genetic reason for her breakdowns.

All of this could easily have made for a very sad or even depressing novel – it did feel somewhat morose to me, and I could have used a touch more of the lighter passages to dispel that – but Huber still instills it with quite a bit of hope, thereby sidestepping a fully negative atmosphere. Her focus on art, and real artists like Picasso, instill the story with interesting historical context as well. Even so, a lack of enough emotional variety, combined with some passages that I feel could have been shortened (such as the story about their cousin Agnes and her troubled marriage to O'Neil), are the reasons why I can't give this novel a full five stars.

However, I still enjoyed The Velveteen Daughter, and I can certainly recommend it, particularly if you're interested in art and the lives of authors of children's classic literature.

![]() This review

first ran in the July 12, 2017

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This review

first ran in the July 12, 2017

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

If you liked The Velveteen Daughter, try these:

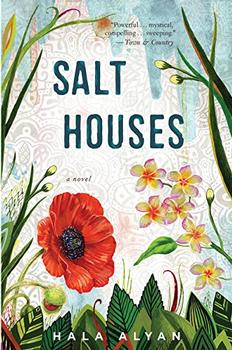

by Hala Alyan

Published 2018

From a dazzling new literary voice, a debut novel about a Palestinian family caught between present and past, between displacement and home.

by Brad Watson

Published 2017

Astonishing prose brings to life a forgotten woman and a lost world in a strange and bittersweet Southern pastoral.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.