Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The America we thought we knew is fractured, says Jonathan Dee in his novel, The Locals, and he sets out to delineate the cracks.

Mark Firth had done well enough as a home contractor, remodeler, and restorer in Howland, his hometown in Massachusetts' Berkshire Hills, but then he nearly lost everything after investing with a Madoff-type who absconded with his funds. After a trip to New York City that coincides with September 11, 2001, Mark finds everything off kilter, not only in New York City, but also when he returns to Howland. One aspect of the disconnect mirroring Mark's own anxiety is the permanent move of New York City financier Philip Hadi and family to their Berkshire summer home. Terrorists are omnipresent. Fear is rampant. Security is imperative.

Mark's regular work quickly fades away, and so he's grateful when Hadi hires him to install an elaborate security system at his house. Normally hidden by foliage, the Hadi house is a mere quarter-mile away from Mark's, perhaps symbolic of the encroachment of city ways on the idyllic. Hadi proves not only a boon to Mark but also to the town of Howland itself. He volunteers as First Selectman and begins to underwrite a good portion of the town's budget during the economic downturn. Simultaneously, taking cues from Hadi and his financial abilities, Mark and his brother Gerry begin to buy up distressed properties, repair them, and rent them out through a federally subsidized program.

Howland prospers, in its own fashion. Mark prospers, not so much or so easily as before. All's well until local resentment of Hadi – mostly spurred by Gerry's uninformed politics – peaks at the same time Hadi loses interest in Howland and leaves.

This is a novel of metaphor and symbolism. First, there's the long opening segment finding Mark grifted out of a credit card while on his 9/11 visit to his New York City attorney, something that nearly ruins his remaining finances. And try this for more symbolism: a celebrity chef opens a $200 prix fixe destination restaurant (in a bankrupt franchise restaurant site in Howland) and badgers surrounding farmers, most a season away from penury, to grow locally sourced exotics like purple kohlrabi.

Whatever part these characters play in Dee's drama of desperation, each is real and frail, human and flawed. Howland had become a town where everyone did everything "toward attracting the moneyed people and then resented them when they came. The rich folks came looking for some country vibe but then seemed to want to protect themselves." Then there's Mark, "so näive and so self-righteous, so confident and so ignorant at the same time." Karen, Mark's wife, is more dissatisfied than supportive, perhaps because of Mark's lack of contribution to the marriage. Haley, their daughter, is a portrait of the intelligent, disaffected teenager. Or the rich, careless, and carefree Hadis, operating "under the misapprehension that the life they were living was the real one, the important, consequential life and everybody else was provincial and out of touch."

The iron core of the narrative, however, occupies the central theme of the 2016 voter revolution of unintended consequences. It is about class, and class resentment; about economic disparity; about moral relativism; about our crumbling social contract; and a paralyzed political process, one so endemic that there's resentment of taxes for services like basic law enforcement and support of local infrastructure. There are references to weather, mud, cold, and the odd summer heat wave, and to Massachusetts' place in American history, and even a short treatise on a local tourist attraction mansion built by a sordid robber baron, and the American money mean point; New York City, plays a solid, central role too.

The pace is literary, with pauses shifting gears to focus on the individual as when Mark's sister, single, 30-something Candace, a passionate woman "haunted by her unlived lives, by the various corpses of possibilities," flails about for help from her brothers with their parents, one with incipient Alzheimer's, the other with his resentful head in the sand. Early in the narrative, Candace also provides a quick glimpse into an educational system where parents are forced to sacrifice for private schooling to keep pace with demands for college entrance. Throughout the novel, there is this same shift from personal conflict to social conflict.

The Locals fades away into a very post-modern conclusion; a more empathic, less raucous Bonfire of the Vanities, or the shadow of a ghost of the classic Spoon River Anthology: a portrait of a time, a place, a people. Dee's novel could find itself in the ranks of the best of recent literary fiction.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in August 2017, and has been updated for the

August 2018 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in August 2017, and has been updated for the

August 2018 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked The Locals, try these:

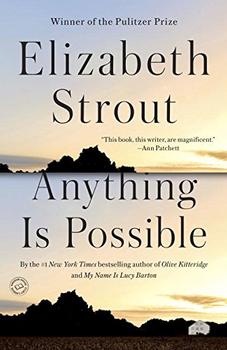

by Elizabeth Strout

Published 2025

From Pulitzer Prize–winning author Elizabeth Strout comes a hopeful, healing novel about new friendships, old loves, and the very human desire to leave a mark on the world.

by Elizabeth Strout

Published 2018

An unforgettable cast of small-town characters copes with love and loss in this new work of fiction by #1 bestselling author and Pulitzer Prize winner Elizabeth Strout.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.