Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

In this novel, set in post-Katrina New Orleans, C. Morgan Babst depicts an apocalypse worthy of dystopian science fiction in arresting detail. While this is a fictional version of the disastrous hurricane and subsequent flood, it represents a tragedy that was and is all too real. As one character walks through the aftermath, he watches as "families burdened with trash bags and coolers picked their way across a desert of mud crisscrossed with torn power lines" and laments, "there was no Moses here leading these people out of bondage, no milk and honey on the other side." This "floating world" is a purgatory, the land that God (and the government) forgot.

The novel unfolds over three months following the disaster (Katrina hit in August 2005), with a middle section capturing the worst of the storm itself. Joe and Tess Boisdoré flee the city before the hurricane hits, but their 28-year-old daughter Cora refuses to join them. Cora finds herself manning a boat with a friend and rescuing people from their flooded homes. In the midst of these heroics, there is a mysterious tragic accident, which Tess, Joe, and their other daughter Adelaide spend the novel attempting to piece together from a largely mute Cora, who was psychologically undone by her experience. Joe and Tess's marriage is already strained by race and class differences, she is white and from a wealthy family, he is black and grew up under more humble circumstances, and it threatens to implode from the stress of these events. Joe is further burdened with looking after his father Vincent, who is suffering from dementia.

The hurricane is an effective backdrop and metaphor for life's smaller tragedies as experienced by the Boisdoré family, the dissolution of a marriage, a parent's slow drift into dementia, the inability to protect a loved one who is seemingly too fragile for the capricious world. Babst uses symbolism liberally and expertly in the novel, the Boisdoré home has been damaged by a magnolia limb crashing through the roof – from a tree the Boisdoré girls played on as children. The hurricane, the tree limb, the incident that damaged Cora's frail psyche, these elements flooded the Boisdoré's metaphorical levee and each family member is submerged in their own personal torment.

Adelaide is the hero, willing to do anything necessary to take care of her sister, whereas Cora comes across as something of a cipher, even in the section devoted to her point of view. It is Babst's writing of Vincent, however, that is the novel's greatest accomplishment. Once a renowned artisan cabinetmaker, Vincent is now a man imprisoned in his own mind, and he delivers a window into the tragic daily degeneration that accompanies Lewy body dementia.

The personal interracial issues surrounding the Boisdoré family are a microcosmic representation of the racial inequality of the city itself as New Orleans, like most major southern cities, was built on slave labor and continues to be largely segregated. When Tess sends Joe to search for Cora, he is turned back by the police, and she is furious that he took "no" for an answer. As a white woman, Tess is unable to fathom why a black man would be hesitant to defy police orders, and Joe is unable to explain this to her. Elsewhere, the police barricade a bridge to protect the sanctity of an upper class white neighborhood from the (largely black) people displaced by the flood. A mentally ill black woman in crisis is dismissed by the authorities, left to fend for herself in disaster.

If this all sounds astonishingly bleak, it is. Babst really piles on the human misery, and for some readers it will be too much. There is no "happy" ending for these characters, at least not now, but there could be, and that's left to the reader to imagine. The fact that they go on, that they endure, is something. The author asks that we reinterpret the idea of ruin. Something may look irredeemable, a city flooded, a mind damaged, a family divided, but nearly anything can be rebuilt. While it's not quite a grand accomplishment of the human spirit, it's a reminder that sometimes, when things look utterly hopeless, just putting one foot in front of the other is triumph enough.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in November 2017, and has been updated for the

October 2018 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in November 2017, and has been updated for the

October 2018 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked The Floating World, try these:

by Terah Shelton Harris

Published 2024

An explosive and emotional story of four siblings―each fighting their own personal battle―who return home in the wake of their father's death in order to save their family's home from being sold out from under them, from the author of One Summer in Savannah.

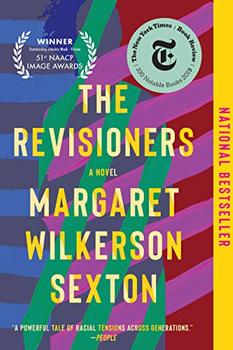

by Margaret Wilkerson Sexton

Published 2020

Following her National Book Award–nominated debut novel, A Kind of Freedom, Margaret Wilkerson Sexton returns with this equally elegant and historically inspired story of survivors and healers, of black women and their black sons, set in the American South.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.