Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Voted 2018 Best Fiction Award Winner by BookBrowse Subscribers

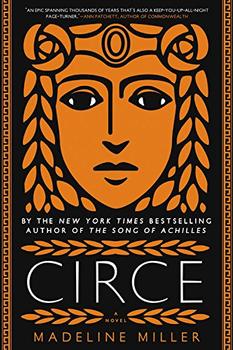

Towards the end of Madeline Miller's novel Circe, the titular nymph is questioned by her son about her life that has already spanned some thousand years. The teenaged Telegonus can hardly hide his astonishment upon discovering that his seemingly low-key mother, whom he has lived alone with for sixteen uneventful years on the secluded island of Aeaea, is related to illustrious gods and mighty Titans, and has been acquainted with already legendary figures in Greece's nascent history. "'Mother! You must tell me everything,'" he pleads.

Yet far from being flattered by this newfound interest in her marginal existence, Circe is almost resentful and retreats from this rare opportunity to shine: "My past was not some game, some adventure tale. It was the ugly wrack that storms left rotten on the shore."

It is a curious, somewhat unfair admission that exposes the mindset of this female divinity. Despite the mythic moments she was witness to and participated in, including being present for the punishment of Prometheus and daring to be the only one of all the gods to secretly offer the wounded Titan a merciful drink to ease his pain, Circe feels she administers no particular control over her destiny, she has no pride in her story. But make no mistake. Her tales are of similar stock to those other gods would eagerly rhapsodize over.

Circe's self-deprecation stems from a lifetime of being used, abused and belittled by gods and mortals alike. From birth, she is quick to realize that regardless of her divine heritage, she is little more than an inconsequence. Her mother, the nymph Perse, wrinkles her nose at her newly born daughter's sex. Pasiphaë, her glory-seeking sister, treats her as a constant object of derision to taunt and mock. And in her adolescence, her sun god father Helios declares his daughter to be "the worst of my children, faded and broken, whom I cannot pay a husband to take."

Rejected, Circe finds solace in sorcery. She learns the power of herbs and potions and begins to surreptitiously use her newfangled witchcraft to self-serving advantage. She gifts her first love, the fisherman Glaucus, with divinity and turns a rival to her beau's affections into a grotesque six-headed sea monster. But even these impressive magical feats are not enough to garner Circe any particular prestige. Her own father dismisses these transformations as instances of fate that Circe was coincidentally spectator to and had no active hand in invoking. Circe soon begins to understand that her marginality is less to do with the fact that she is a nymph, "least of the lesser goddesses," than that she is a woman. This becomes especially apparent when, exiled on Aeaea, Circe offers drowning wayward sailors refuge in her home. Time and time again the sailors turn on their solitary hostess. Even displaying her divinity makes no difference: "I was alone and a woman, that was all that mattered." Her solution is to turn these lustful debauched men into swine.

Much of Circe is an exploration into what it means to be female in a world of men and monsters. While it is usually tenuous to compare an author's latest novel to previous work, it does feel as if Miller wrote Circe as a conscious inversion of her prize-winning debut The Song of Achilles in nearly every aspect. The pool of inspiration may be the same – primarily Homer's epics – but whereas Achilles was very much a book about mortal men coming to grips with their own version of masculinity, Circe is about a divine woman trying to consolidate her myriad feminine identities as daughter, sister, lover, mother, witch, and goddess.

Even the narrative frames in each of Miller's binary novels take on quasi-gendered forms. In Achilles the story arc is as steady and as unwavering as the trajectory of the sun. From the start the reader knows more or less where the tale will set. In Circe there's a fluidity to plot and narrative that is similar to the tides that surround the nymph's adopted home island. Characters come and go. Those well-versed in Greek myth will particularly delight in cameos from Jason of Argonauts fame, Minos and his namesake Minotaur, and Daedalus, father of that cautionary figure Icarus. That said, Miller provides plenty background for even those unfamiliar with Greek mythology to enjoy her adaptations of these classic myths.

By the end of her transformative tale, Circe comes to realize that she has far more control and power over her destiny than she was initially led to believe. Graceful and majestic in equal measures, Circe is sure to leave an indelible impression on readers both new and returning to Miller's singular reworkings of Greek myths.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in April 2018, and has been updated for the

May 2020 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in April 2018, and has been updated for the

May 2020 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked Circe, try these:

by Caro De Robertis

Published 2025

Perfect for fans of Circe and Black Sun, this bold and subversive feminist retelling of the Greek myth of Psyche and Eros explores the power of queer joy and freedom.

by Ferdia Lennon

Published 2025

An utterly original celebration of that which binds humanity across battle lines and history.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.