Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Reporter's Undercover Journey into the Business of Punishment

by Shane BauerAfter spending over two years in Iran's notorious Evin Prison for supposedly crossing the country's border illegally, it would make sense if Shane Bauer never wanted to set foot in another detainment facility. Yet this Mother Jones reporter chose to go undercover as a corrections officer at a for-profit prison in Louisiana, and the result is a damning portrait of the business of incarcerating Americans, and the legacy of racism in the criminal justice system.

Bauer set out to gain firsthand insight into for-profit prisons, which hold about 133,000 people behind bars in America and are reticent about disclosing information to the media. He proceeds through the few weeks of training provided by Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) at Winn Correctional Facility in Winnfield, Louisiana, observing as recruits continually drop out and instructors fail to show up for class. Soon, Bauer is working 12-hour shifts and mandatory overtime for less than $10 per hour—a tense situation that is exacerbated by inmates taunting and baiting the officers. It is unsurprising that many of the prison's employees lack commitment to the job and opt to cut corners.

Perpetually understaffed, and particularly lacking social workers and healthcare personnel, the prison is a violent, chaotic place with frequent stabbings, prisoners left in isolation on suicide watch and constant battles of wills between exhausted corrections officers and miserable inmates. The twenty-nine mandated staff positions are almost never filled during Bauer's time at Winn, as management emphasizes cost-cutting above all else. In the vacuum, prisoners are denied time outdoors and access to education or any other rehabilitation-oriented programs, while the staff engages in low-level corruption like allowing inmates to have cell phones and keeping their confiscated contraband.

Bauer becomes increasingly bitter and stressed, even away from the prison. He writes about himself with a narrative distance and a limpid style, guiding the reader through his personal experience without dramatization. Arguments with inmates and other officers, his feelings of helplessness and depression, and the mental issues suffered by those around him are presented without judgment, didactic rhetoric, or shrill denouncements. His journalistic detachment allows the reader to process his feelings of anger and anxiety alongside him.

The book alternates chapters about Bauer's experience with chapters relating the history of forced prison labor and "convict leasing," a system established in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War that essentially spawned the private prison industry. A crucial loophole in the Thirteenth Amendment (ratified in 1865) facilitated this perpetuation of forced labor, overwhelmingly used by the state against black men. The amendment ended slavery "except as punishment for a crime," and businessmen and government officials exploited this phrasing to use convicts in a system not much different from chattel slavery. From plantations to railroads to mines, incarcerated black men were tortured and worked literally to death well into the twentieth century. But public awareness of these conditions did not lead to change: "It was only when [convict] leasing stopped bringing enormous profits to powerful businessmen and state treasuries that the system came apart," Bauer explains. As the system became more competitive, with multiple companies bidding the government for contracts to lease inmates, prices for these contracts became high enough that it was no longer an attractive deal for the companies.

The juxtaposition of Bauer's experience with the historical chapters provides a rich context, helping the reader to understand how the present system came to be. This structure also helps the narrative build to a climax, as the parallel paths of Bauer's increasing anxiety and the often upsetting history of convict leasing crescendo together.

After four months at Winn, Bauer's marriage and mental health are suffering, and when his photographer is arrested trying to photograph the outside of the prison, he hurriedly quits before his research can be confiscated. To the reader, who has vicariously experienced his distress and anger building, his abrupt flight comes as a relief, a feeling similar to when a main character in a fictional story escapes a dangerous trap.

But this resolution isn't like a novel—the inhumane conditions, the stories of violence, and the pervasiveness of state-sponsored exploitation and mass incarceration of African-Americans linger well after Bauer has reentered his normal life. For millions of people, predominantly black men whose labor is being exploited in public and private prisons who can't return to another state and another job as Bauer does, this intersection of racism and greed means incarceration for profit remains a part of life, and it will prove a lasting stain on what America calls criminal justice.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in September 2018, and has been updated for the

July 2019 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in September 2018, and has been updated for the

July 2019 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked American Prison, try these:

by Adam Plantinga

Published 2024

When a high-security prison fails, a down-on-his luck cop and the governor's daughter are going to have to team up if they're going to escape in this "jaw-dropping, authentic, and absolutely gripping" (Harlan Coben, #1 New York Times bestselling author) debut thriller from Adam Plantinga, whose first nonfiction book Lee Child praised as "truly ...

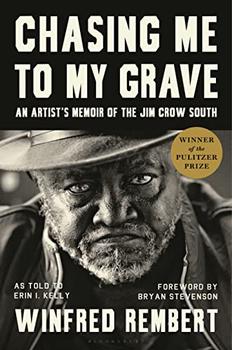

by Winfred Rembert

Published 2023

Winfred Rembert grew up in a family of Georgia field laborers and joined the Civil Rights Movement as a teenager. He was arrested after fleeing a demonstration, survived a near-lynching at the hands of law enforcement, and spent seven years on chain gangs.

If there is anything more dangerous to the life of the mind than having no independent commitment to ideas...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.