Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Memoir of Life, Death, and Everything That Comes After

by Julie Yip-WilliamsJulie Yip-Williams was never supposed to make it to her first birthday. Born with severe congenital cataracts that left her blind, she was considered a liability in late-1970s Vietnam. There were no trained doctors who could help her and little chance of leaving a war-torn country, so her grandmother decreed that the two-month-old girl would be taken to an herbalist who would administer a potion to send her to sleep forever. To Julie's parents' relief, the herbalist refused to carry out the death sentence, and they brought their daughter safely back home. When Vietnam expelled its ethnic Chinese in 1979, the family survived 11 days on the open sea to reach Hong Kong by boat. Later that year the U.S. Catholic Church sponsored their relocation to San Francisco, and three-year-old Julie had surgery to partially restore her sight.

It was miracle enough to have survived these first few years, but despite being partially sighted Julie got a full scholarship to Williams College and later graduated from Harvard Law School. She joined a Wall Street law firm, and she and her husband Josh had two daughters, Mia and Belle. In the summer of 2013, while in California for a family wedding, she went to a hospital in gastrointestinal distress and was diagnosed with stage IV, metastasized colon cancer. Aged 37, she had immediate surgery to remove the mass from her colon, but over the nearly five years that remained of her life the cancer spread into her lungs and ovaries.

Julie dubs herself "a somewhat ruthless realist." Early on she vowed that she would do nothing desperate or bizarre in her quest for healing. In contravention of what she calls the American "hope industrial complex," she expresses a belief that fear of death should not win out over love of life. For her, acknowledging the inevitability of death meant she could prioritize quality of life versus quantity of days remaining. From a place of acceptance, she could make preparations to ease her family's life after she was gone.

As practical as she insisted on being, she also left room for spirituality to surprise her. Her cultural background included Buddhism and ancestor worship. On multiple occasions she also consulted psychics and palm readers, one of whom detected her traumatic past – she didn't learn the full story of her grandmother's attempt to have her killed until she was 28. Ghosts and spirits were a serious topic of discussion in this family; early in the book she matter-of-factly reports that her daughter Belle saw ghosts in the house they rented near Beverly Hills while she was recovering from surgery.

This memoir is painfully honest in places, as when Julie admits to hating people who have her same diagnosis but have been cured. There's no Superwoman mask here; when she is angry, bitter, or has dark thoughts, she says so. Yet she also finds moments of hope and happiness in cooking, having deep conversations, and experiencing wonder in natural settings like on a vacation to the Galápagos Islands. She can even summon up the spirit to joke with Josh about the "Slutty Second Wife" she imagines replacing her soon.

It's worth noting that Julie did not perhaps have a typical cancer experience. Wealth and connections allowed her to get strings pulled. She avoided wait times, got into medical trials, and paid for a lab to culture her cancer cells in fruit flies to try to develop personalized treatment. She acknowledges how lucky she was to live near Memorial Sloan Kettering, a top cancer center in New York City, and she was also fortunate to never have to work again after her diagnosis. More often, cancer represents a heavy financial burden for its sufferers.

The book resembles a set of journal entries or thematic essays, written at various times over her five years with cancer. Although the contents are grouped chronologically, the order of the pieces under the year headings can seem random. Also, some stories are told more than once, particularly in the final chapters as she starts summing up her life. An editor might have combined or cut some passages to avoid that repetitiveness.

All the same, I appreciated the way she characterizes life as a miracle and writes of how loved and valued she felt throughout her cancer experience – a reversal of the worthlessness her disability once made her feel. In alternating between hope and horror, anger and awe, The Unwinding of a Miracle feels true to life. A pair of letters, one written to her daughters and another to her husband, are particularly wrenching, as is the epilogue Joshua Williams wrote in June 2018, three months after Julie died at age 42. This posthumous memoir stands as a testament to a remarkable life of overcoming adversity, asking questions, and appreciating beauty wherever it's found.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in February 2019, and has been updated for the

March 2020 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in February 2019, and has been updated for the

March 2020 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked The Unwinding of the Miracle, try these:

by Rod Nordland

Published 2025

A legendary New York Times war correspondent delivers his unforgettable final dispatch: a deeply moving meditation on life inspired by his sudden battle with terminal brain cancer.

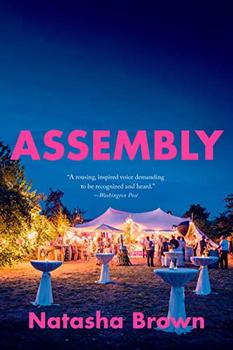

by Natasha Brown

Published 2022

A woman confronts the most important question of her life in this blistering, fearless, and unforgettable literary debut from "a stunning new writer" (Bernardine Evaristo).

A library, to modify the famous metaphor of Socrates, should be the delivery room for the birth of ideas--a place ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.