Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

In the introduction to In the Dream House, Carmen Maria Machado (a National Book Award finalist for her collection of short stories Her Body and Other Parties) tells us she is writing in part to dispel an "archival silence" about abuse in queer relationships. In other words, there is little documentation about this phenomenon available, it has rarely permeated popular culture, and as such, it is largely invisible. She later notes that lesbian relationships in particular are presumed to be idyllic—two women sharing their feelings openly, treating one another with respect and unwavering loyalty—when this is certainly not always the case. Queer women are people, and are just as likely to behave monstrously as anyone else.

Machado is attending the Iowa Writers' Workshop for her MFA in 2011-2012 when she meets the charismatic woman who will become her abuser through a friend and the two begin dating. The relationship becomes serious alarmingly fast, despite some early warning signs that something is amiss (general controlling behavior that turns physical on a trip to the woman's parents' house in Florida). Machado's abuser is accepted to a writing program in Indiana and moves there, into the Victorian home referred to throughout as the Dream House. Subsequently, the author begins driving from Iowa to Indiana every other weekend to visit. The distance stokes her abuser's insecurities, and she begins accusing Machado of being unfaithful. All manner of abusive terrors ensue, and the author recounts the psychological nightmare of her experience in prose that is both bluntly confessional and poetically allusive.

Machado narrates her story in short chapters (ranging from a single sentence to a few pages), each of which is titled after a different trope or narrative component, i.e., "Dream House as Inciting Incident," "Dream House as Bildungsroman," "Dream House as Chekhov's Gun." Each of these tropes (which range from literary to cinematic to folkloric) serves as a lens through which Machado examines her abusive relationship with the woman from the Dream House. In this way, the author is recounting her own narrative, but also building on a foundation of storytelling that is timeless. There's a villain, but the hero doesn't know she is in danger. There's a haunted house, and we want to tell the hero to get out of there. There's ominous foreshadowing around every corner, and we want to grab her by the lapels and shake her, tell her, "This is not right!" Which is to say, Machado is a master of dramatic tension, and brilliantly illustrates the constant, low-level dread and psychological stress one feels in a relationship with an abusive person.

It's human nature to absorb a story like this and wonder of the victim, "Why didn't she just..." or believe, somewhere in the back of one's mind, "This would never happen to me..." Machado anticipates this, and even finds fault with her naivete in retrospect, but hindsight is 20/20, and again, there's that archival silence. It's so difficult to recognize what's happening if you've never seen it before, and it's even harder to respond appropriately to circumstances you'd never imagined might happen to you. She explains in "Dream House as Public Relations":

I have spent years struggling to find examples of my own experience in history's queer women...wondering what would happen if they had let the world know they were unmade by someone with just as little power as they. Did Susan B. Anthony's womanizing extend to psychological torment? What did Elizabeth Bishop really say to Lota de Macedo Soares when she'd been drinking heavily? Did their voices crawl with jealousy? Did they hurl inkwells and figurines? Did any of them gingerly touch their bruises and know that explaining would be too complicated? Did any of them wonder if what happened to them had any name at all?

If all this makes In the Dream House sound like an intellectual exercise, that's an accurate assessment. But it's also an incredibly moving piece of art. It's a dark dissection of an everyday horror that is no less terrifying for its pervasiveness. And perhaps most importantly, it speaks an ugly, irrevocable truth where there had been silence—it is a vital, monumental addition to the queer canon.

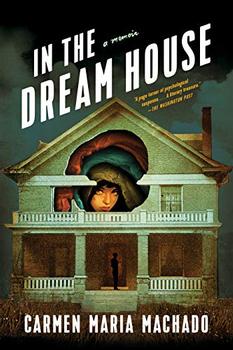

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in January 2020, and has been updated for the

April 2021 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in January 2020, and has been updated for the

April 2021 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked In the Dream House, try these:

by Tia Levings

Published 2026

"Today it hit me when he hit me, blood shaking in my brain. Maybe there wasn't a savior coming. Maybe it was up to me to save me."

by Melissa Febos

Published 2025

From the national bestselling author of Girlhood, an examination of the solitude, freedoms, and feminist heroes Melissa Febos discovered during a year of celibacy. A wise and transformative look at relationships and self-knowledge.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.