Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A True Story of China, the FBI, and Industrial Espionage

by Mara HvistendahlWhat differentiates Mara Hvistendahl's The Scientist and the Spy from other contemporary nonfiction takes on espionage is its unusual premise—corn seed patents. Though readers of this tightly spun book may leave with a muddled view on the threat of Chinese espionage, they will walk away with a good story and an impressive knowledge of seed engineering.

The book opens in 2011 with an Iowa state trooper taking the names of three suspicious men, one of whom was caught rummaging through a private field containing patented seeds. Though the culprits get off the hook, the Chinese names the trooper jots down become important, setting off a string of events that put the FBI on the tail of corporate thieves working for a Chinese seed company called DBN.

At the center of this caper are three individuals, each with their own plans and motivations. There is Robert Mo, a Chinese citizen who has settled and raised his family in Florida but failed in his pursuit of the American Dream; Kevin Montgomery, a Midwestern agronomist who dreams of developing his own seed line; and Mark Betten, an FBI agent tasked with preventing corporate espionage.

Robert Mo ("the Spy") is the author's protagonist of sorts, and Hvistendahl attempts to garner sympathy for his predicament as the FBI's net begins to close tightly around him. He's not the ringleader, but rather the main, increasingly anxious, participant in a larger conspiracy.

Finding trouble landing a decent paying job after finishing graduate school in the United States, Robert begins working for his billionaire brother-in-law, the CEO of DBN. He soon finds himself partaking in risky endeavors, including raiding private property throughout the upper Midwest looking for Monsanto and Pioneer corn seeds to steal. The ultimate plan is to transport the seeds back to China to be reverse engineered, illegally, by DBN.

To speed up the process, Robert enlists the help of agronomist Kevin Montgomery ("the Scientist"), whom he introduces to DBN. Kevin's ambition to potentially sell his own seeds to DBN someday blinds him to the full extent of their nefarious deeds. Plus, the company pays him well. However, Kevin becomes irritated by how dismissive his Chinese handlers are of his knowledge. Suspicious of his bosses' true intentions already, Kevin is convinced by FBI agent Mark Batten to turn informant.

On the trail of DBN's plot, Mark and the FBI spare no effort in trying to bring Robert Mo and his DBN colleagues to justice. Confounding their efforts is the burden of proof required to catch corporate spies. Unlike in China, where those accused of espionage are arrested (and often disappear) immediately, the FBI must follow legal procedures and try to tie the espionage to the Chinese. Inevitably, this allows all of DBN's employees in the U.S., except Robert Mo, to escape back to China.

Hvistendahl writes about the science of corn adeptly. Her background in communicating complex scientific topics for the layperson pays off here. (She was formerly a journalist writing for Science magazine while living in China.) The book never gets bogged down in technical babble. Her pacing is stellar, with short chapters quickly hopping between the three main characters. Her writing style—a mix of journalism and suspense—helps mitigate the more technical components of the story. Throughout, she tries very hard to emphasize the human element in all of this—the Chinese citizen with American children who feels trapped, the corn seed scientist who feels underappreciated, and the FBI agent who is just doing his job.

Looming in the background of Hvistendahl's narrative is the fact that the U.S. government is fighting for what many might consider to be less than sympathetic corporations—Monsanto and Pioneer. The author attempts to paint Robert Mo and his pursuit of the American Dream in a compassionate light, but this is where the book falls flat. Even when she interviews Mo in prison near the end of the book (he served three years beginning in 2017), it's difficult to empathize with him. While Hvistendahl seems to believe there is moral ambiguity in the choices he made, the reader may not feel the same.

She also spends an inordinate amount of time diminishing the danger of Chinese espionage and technological theft. Her book is written in a disarming manner that comes off as well-researched and authoritative. However, the way she writes about Chinese, state-sanctioned economic espionage reads like it was reviewed by censors at the China Daily.

China has a well-documented disregard for intellectual property. To do business there, Western firms must first turn over their proprietary technologies to the communist government. Frequently this proprietary technology ends up being re-engineered by competing Chinese corporations with more access to the Chinese market. At one point, the author even broaches a straw-person argument about how the West has stolen technologies from China too—back in ancient times (e.g., gun powder). Segments like this diminish the credibility of the otherwise well-written book, but will likely keep her from being banned if she wishes to return to China.

Though it's difficult to side with Monsanto and Pioneer, whose business practices are the subject of various disturbing reports, Hvistendahl's relentless critique of how the American government spent resources attempting to prevent China from stealing corporate technologies is also clumsy. The FBI is a federal police agency. If people are trying to steal technology and it may cost the U.S. economy billions of dollars (and many jobs), one would hope they would try to catch the criminals. Based on this case and several others, the author essentially accuses the FBI of racial profiling. It's worth noting that the week before her book was published, the FBI arrested the head of the Chemistry and Chemical Biology Department at Harvard University, Charles Lieber, for selling his research to China and lying about it to the Department of Defense. Charles Lieber is Caucasian.

In the end, it wasn't racism or racial profiling that got Robert Mo arrested. He was a Chinese national living in the United States who got caught doing something he knew was illegal and risky. Like it or not, Western society depends on capitalism, property ownership and the health of large corporations. The author's banal defense of China in this book rings hollow and unconvincing, which is a shame, because overall, The Scientist and the Spy is an extremely well-written, engaging story.

- Stephen Mrozek

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in March 2020, and has been updated for the

February 2021 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in March 2020, and has been updated for the

February 2021 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked The Scientist and the Spy, try these:

by Amelia Pang

Published 2022

In 2012, an Oregon mother named Julie Keith opened up a package of Halloween decorations. The cheap foam headstones had been $5 at Kmart, too good a deal to pass up. But when she opened the box, something fell out that she wasn't expecting: an SOS letter, handwritten in broken English by the prisoner who'd made and packaged the items.

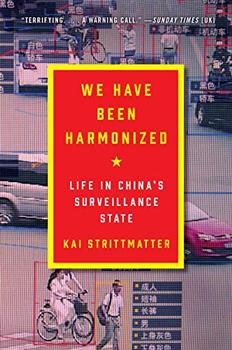

by Kai Strittmatter

Published 2021

Hailed as a masterwork of reporting and analysis, and based on decades of research within China, We Have Been Harmonized, by award-winning correspondent Kai Strittmatter, offers a groundbreaking look at how the internet and high tech have allowed China to create the largest and most effective surveillance state in history.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.