Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Afia Atakora's debut novel opens with the ominous sound of a baby's cry. It's in her dutiful response to that cry that we meet Rue, a second-generation healer and recently freed slave tending to a post-Emancipation town in an unnamed part of the American South. The town is the home of former slaves, their "prosperity," as one character says. But all is not well here. From the beginning, the setting evokes much of the complicated history of slavery in America and the thwarted promise of freedom in the Reconstruction era. In the tradition of Toni Morrison's Beloved and more recently Jesmyn Ward's Sing, Unburied, Sing, Conjure Women largely uses magic and motherhood to explore the reverberating effect of slavery on all of the people and communities it irrevocably binds together.

One of the primary questions the novel asks is this: even in the time of freedom, who is really free? And in what ways must we "conjure" freedom for ourselves? Rue's mother May Belle is afforded a certain level of status and freedom even before the war because of her magic and healing powers. We learn that "…because she kept their property from dying, white folks let her have it. They let her have her own way." This meant a special dispensation from field work and greater access to things like blankets and soap. And May Belle always seems to find what she needs even if she has to create it for herself. We are told that "...if Miss May Belle insisted on a thing, she'd have it, as good as willing it into existence." However, this power and this "freedom" ultimately do not protect her or those she loves from sexual violence and death.

Interestingly, freedom doesn't protect all of the white characters in the novel either. Varina is the young mistress of the plantation, and the continual impudence and impetuousness of her childhood years seems to demonstrate how much freedom she has. Though she is told on numerous occasions that her father wouldn't like if she were found spending too much time with Rue and the other slaves, Varina routinely visits the slave quarters and ventures off into the woods alone with Rue. Varina's privilege even extends to dictating the freedom of others. In anticipation of her marriage, she has Rue and Sarah, another young slave, signed over to her as her personal property. But Varina's freedom proves limited to the extent to which she can remain a "proper lady." After her coming out party, which she makes Rue watch from the inside of a latched chest, Varina is raped by an unnamed "gentleman." She suffers the assault in relative silence and tells no one afterward because in doing so she would become a "ruined" woman—stripped of her status, dignity and many of her other freedoms.

Similary, Rue is bound by her status in the world and by her role as the conjure woman's daughter, as she is expected to follow in her mother's footsteps. Even after the war and the onset of de jure freedom, Rue is still bound. Early on we are told, "Freedom had come after the war for all black folks. All excepting Rue, she felt, for she was born to healing and stuck to it for life. And stuck to this place." It's in the time of freedom that readers come to understand how relative a term it truly is. Though she has done much to try to safeguard her town, Rue struggles to find happiness in a role and in a life she did not choose for herself. And while there are genuine moments of "magic," the novel demonstrates that ultimately real "conjuring" occurs, as it often does in life, in much more familiar and ordinary ways. It manifests in love and choice and money. Young Rue is fascinated by the silver dollars her mother receives for her work. We learn that "Miss May Belle had used to turn coin on hoodooing. As a slave woman she'd made her name and her money by crafting curses." And later, when Rue witnesses her mother turn a fellow enslaved woman into a bird, a true moment of magic, what makes the biggest impression on Rue is that her mother sprinkles those same silver dollars in the river bed so that they can light the woman's way to the North.

Conjure Women is a novel rooted as much in its place as its people. It is steeped in natural imagery, linking (in ways as complicated as the history of black people in the Americas) those enslaved, and later dispossessed people, to the places they inhabit. These spaces are treacherous, barren and haunted, yet they are also restorative and transformational. These dichotomies are one of the hallmarks of the book, creating a kind of undulating suspense and release, hope and loss, elation and melancholy that ultimately reaffirms what the characters in the novel have always known: despite their magic, this life and this work could never have a fairy tale ending. But one thing is certain: that Atakora is able to bring together these myriad characters, plotlines and themes so masterfully is magic in and of itself.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in April 2020, and has been updated for the

April 2021 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in April 2020, and has been updated for the

April 2021 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked Conjure Women, try these:

by Cebo Campbell

Published 2024

In a world without white people, what does it mean to be black?

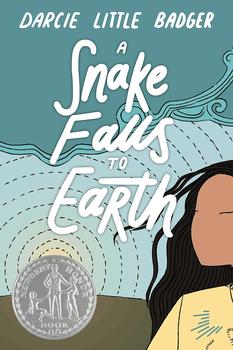

by Darcie Little Badger

Published 2024

Nina is a Lipan girl in our world. She's always felt there was something more out there. She still believes in the old stories.

The moment we persuade a child, any child, to cross that threshold into a library, we've changed their lives ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.