Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

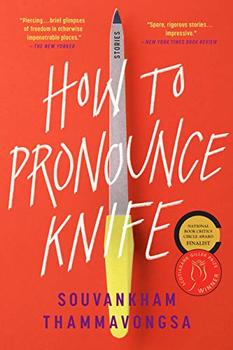

Many examples of immigrant fiction dedicate a portion of their storytelling to exploring details of homelands that their characters have abandoned—food, rituals, sights and sounds of countries sorely missed. It is striking how little time Thammavongsa has for such wistfulness. Throughout the 14 stories collected in How to Pronounce Knife, nearly all of which follow Lao immigrants and refugees building new lives in unnamed towns across Canada, not once do we encounter a character homesick with nostalgia.

Laos may flow in the bloodstream of these stories, but the Southeast Asian country itself remains an invisible presence, a land that lies half a world away. Characters make brief mention of the "bombed-out country in a war no one ever heard of," but they rarely delve into their particular reasons for leaving, and the book contains little about the history, politics and culture of Laos.

By limiting cultural particularities, Thammavongsa steers the reader closer to a general experience of alienation bound up with the immigrant experience. After all, we may not all share the same cultural touchstones, but most of us know what it means to feel out of place, brushed off and excluded. In these stories, it is misunderstandings in customs and language that continually threaten to expose characters as "other."

Thammavongsa expertly illustrates feelings of vulnerability in the stories by telling many of them from the point of view of children. In the poignant title story, a young girl brings home a book to practice her English and asks her father to help her with a new word that has tripped her up. He insists it is pronounced "kahneyff." The next day, the girl is humiliated in front of the entire class when she is made to read aloud. In the similarly themed "Chick-A-Chee!" an enthusiastic father drives his children to a posh neighborhood so they can join in the Halloween fun. They go from door to door collecting candy, unaware the activity is called "trick-or-treating" (see Beyond the Book) and not, as they were informed by their father, "chick-a-chee."

Elsewhere, Lao women take center stage. In "Paris," a woman works in a chicken plant where she dreams of getting a nose job so she can blend in with the white women, be offered a better paid position in the front office and draw the attention of her married boss. In "Picking Worms," a mother attempts to instill the importance of hard work in her 14-year-old daughter by getting her a job in the worm harvesting farm where she works herself; the mother's hopes for a deserved promotion in this most menial of professions are dashed by the unlikeliest of candidates. And in "Randy Travis," a housewife withdraws into a fantasy romance with a famous country music star. Her husband attempts to indulge her newfound interest by buying her concert tickets and dresses in cowboy boots and flannel shirts in an effort to win back her affections. The ending is a true tear-jerker.

Many of Thammavongsa's characters are in a sort of cultural chrysalis, willingly shedding their heritage in an attempt to better their futures. Some Anglicize their names. Some obsess on trivial facets of American culture. Some fantasize about being able to look less Lao. The author doesn't offer any judgement on how they are, in essence, forced to deny an integral part of their ethnic identities in order to fit in and be treated, if not as locals, then at least as equals, but instead focuses on the realities of their situations: Their need to make a living, the limited and often demeaning work opportunities available to them, their desire to build a better life for their children that simply doesn't afford them the luxury to question whether they are losing or compromising their cultures and identities.

These stories never rely on twists or a-ha moments. Their power lies in the quiet unfolding of graceful plainsong prose that flows across the page like pearlescent silk. They are deeply affecting, humorous and heartbreaking in equal measure. How to Pronounce Knife is a beautiful collection that leaves an indelible impression.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in May 2020, and has been updated for the

May 2021 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in May 2020, and has been updated for the

May 2021 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked How to Pronounce Knife, try these:

by Anthony Veasna So

Published 2022

A vibrant story collection about Cambodian-American life - immersive and comic, yet unsparing - that offers profound insight into the intimacy of queer and immigrant communities.

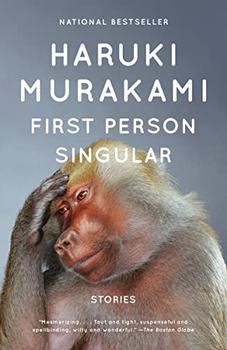

by Haruki Murakami

Published 2022

A mind-bending new collection of short stories from the internationally acclaimed, Haruki Murakami.

We should have a great fewer disputes in the world if words were taken for what they are

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.