Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Aria opens with the abandonment of a baby girl in a Tehran alley in the winter of 1953. The infant is soon discovered by Behrouz, an army driver who becomes a surrogate father to her and names her Aria. This opening draws the reader into Nazanine Hozar's debut novel, which chronicles the life of its titular character until 1981. Hozar skillfully weaves this coming-of-age tale against the brewing discontent in Tehran as the nation surges toward the 1979 revolution and the rise of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Aria explores an array of experiences from a female perspective, including childbirth, love, marriage, loss, mothering, inheritance and abuse. While Behrouz, perhaps the novel's most sympathetic character, and other men in the book are not without their complexity and purpose, the plot is firmly driven by the life events of its women. Aria is divided into four parts, each with a focus on one of four main female characters: Zahra, Fereshteh, Mehri and Aria.

The beginning of the novel centers Zahra, Behrouz's velvet-high-heel-and-red-lipstick-sporting wife. Zahra's actions toward Aria are reprehensible. She repeatedly locks Aria out of the house, forcing her to spend nights on a balcony, and neglects her to the point where she develops trachoma, which threatens to destroy her eyesight.

When Zahra pulled her hair, Aria awoke, too shocked to cry. Zahra smacked Aria's face with the back of her hand, knowing that inflicted the most hurt. Blood dripped from a cut on Aria's cheek left by Zahra's wedding ring.

This early domestic maltreatment provides the book's first instances of violence, a theme that recurs not only between characters but through state violence from SAVAK (the Shah's secret police) and the rise of Islamic fundamentalism throughout the 1960s and '70s. Zahra's brutality is nuanced, with her backstory revealing the origins of her anger and providing more context for her actions long after the conclusion of her focal section. Hozar skillfully crafts complexity not only for Zahra but the other main characters as well, allowing their characterizations to percolate throughout the narrative and imbue the novel with a satisfying richness and interconnectedness.

Aria leaves her first home with Zahra and Behrouz in south Tehran when she is taken in by a wealthy woman, Fereshteh, in the northern part of the city. Despite this relocation, the plot keeps Aria moving between the affluent northern and impoverished southern areas. Hozar's prose paints a vivid portrait of Tehran, its urban topography and the contrasts between its neighborhoods. The author moves the reader along the streets as her spirited and compelling, if not always sympathetic, protagonist traverses the city and its social classes. The detailed descriptions of Tehran are not overburdening, and should be accessible and enjoyable for readers unfamiliar with the setting. Still, these descriptions, along with references to political figures and events, will likely offer an even deeper richness for those with a knowledge of the city and Iranian history.

The disparity between north and south Tehran and growing fission between classes are made apparent in comments from the characters. In one scene, Aria's friend Mitra explains why their mutual friend, Hamlet, is missing from school:

"His father took him out of our class," Mitra said, quickly wiping a tear from her cheek. "He doesn't like people like me or you. But mostly people like you."

"Non-Christians?" Aria asked.

"No. People without money," Mitra said.

The starkness of Hozar's dialogue cuts to the essence of the overlapping, clashing nature of relationships between characters. The novel's third-person narrative allows for an ambitious blend of storylines and people, though some, such as Aria's childhood neighbor Kamran, seem to evaporate until they become useful again in the context of the growing political and social unrest. At times, the shift between storylines can be jarring, but the book is consistently engaging and fast-paced throughout.

Aria is a complex chronicle of growth amidst burgeoning violence, uprising and a nation grappling with class differences. The relationships between the novel's plethora of characters, like its political themes, are likely to sit with readers long after the epilogue and will no doubt make for lively discussion in book groups.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in September 2020, and has been updated for the

July 2021 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in September 2020, and has been updated for the

July 2021 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked Aria, try these:

by Marjan Kamali

Published 2025

From the nationally bestselling author of the "powerful, heartbreaking" (Shelf Awareness) The Stationery Shop, a heartfelt, epic new novel of friendship, betrayal, and redemption set against three transformative decades in Tehran, Iran.

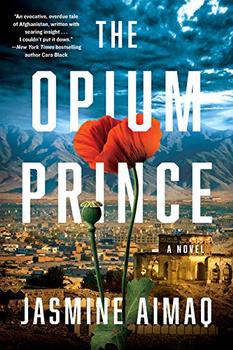

by Jasmine Aimaq

Published 2022

Jasmine Aimaq's stunning debut explores Afghanistan on the eve of a violent revolution and the far-reaching consequences of a young Kochi girl's tragic death.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.