Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

On June 5, 1985, Natasha Trethewey's mother, Gwendolyn Turnbough, was murdered by her ex-husband, Joel Grimmette. It took Trethewey 30 years to feel ready to truly reckon with the trauma of this event and the years of abuse that preceded it. In a piercing, extraordinary memoir, she excavates the chasm of the loss and holds its terrible artifacts up to the light of day.

Memorial Drive begins with the author's childhood in Mississippi in the late 1960s and early '70s, where she grew up surrounded by doting family who could not entirely shield her from the racism of the time and place. Trethewey is the biracial child of a Black mother and a white father, and the family was often subjected to threats and intimidation. (She notes that her mother gave birth to her in a hospital that was still segregated on April 26, 1966, the 100-year anniversary of Mississippi's celebration of Confederate Memorial Day.) Her parents divorced when she was six years old and Trethewey and her mother moved to Atlanta; Gwendolyn met Joel soon after and the two got married. Joel was often left to babysit Trethewey while Gwendolyn was at work. When she upset him, he forced her to pack a bag and get in the car, then drove her in a loop around the city, claiming he was going to leave her somewhere alone. She was in the fifth grade the first time she heard Joel hitting her mother in the next room.

Amid the horrors recounted in the memoir is Trethewey's coming-of-age story, as the person she is today — the writer she is today — was forged in the fire of this trauma. She recalls receiving a diary from her mother at age 12, only to discover a short time later that Joel had picked the lock and read her private thoughts. Her response was to turn her diary entries into a virulent direct address to her abuser, telling him exactly what she thought of him. "In my first act of resistance," she writes, "I had inadvertently made him my first audience...I had begun to compose myself."

In 1983, when Trethewey was a senior in high school, Gwendolyn left Joel, taking the author and her little brother Joey with her. Shortly thereafter, Joel showed up at a high school football game looking for Trethewey. Uncertain how to react, she greeted him as she always did, "Hey, Big Joe." She later learned that Joel told a psychologist while he was hospitalized that he'd brought a gun and planned to shoot her but couldn't go through with it after she said hello to him. On the one hand, this was certainly a blessing. On the other, she notes that had he killed her that night, he would have been arrested and almost definitely imprisoned, perhaps never finding the opportunity to murder her mother. It is a chilling realization and the author's struggle with survivor's guilt is rendered with forthright clarity.

In the two years that followed, Joel tried to kill Gwendolyn, served a year in prison, and then immediately began threatening her life again when he got out. Trethewey includes evidence from her mother's case, such as police reports and transcripts of phone conversations between Joel and Gwendolyn in the days leading up to the murder that are hard to read but essential to understanding how difficult it is for a victim of abuse to get help. Even in this case, when the police took the situation seriously (it is not at all uncommon for victims to be ignored or disbelieved by the authorities), they did not adequately protect Gwendolyn.

The memoir is bookended by the author's recounting of a recurring dream. She and Gwendolyn walk around a circular path. Joel steps out of the shadows, Trethewey greets him as she always did, "Hey, Big Joe," and they continue walking. Shortly thereafter, he appears again, this time holding a gun. She shouts "No!" and tries to shield her mother, waking herself up in the process. It is a representation of her guilt, and one repeated symbol among many in the memoir. Of this dream and a particularly vivid and traumatic memory from childhood, she writes, "What matters is the transformative power of metaphor and the stories we tell ourselves about the arc and meaning of our lives." For a writer especially, metaphor is a powerful tool. But Memorial Drive offers insight and instruction for anyone who has experienced trauma. The memories, dreams and other ephemera that haunt us may ultimately prove key to finding meaning and hope (or perhaps just the ability to put one foot in front of the other) in our darkest hours. It's a powerful record of grief, abuse and the cleaving of the self that often occurs in conjunction with a life-altering tragedy, an acute and far-reaching manual for making sense of the senseless.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in September 2020, and has been updated for the

June 2021 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in September 2020, and has been updated for the

June 2021 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked Memorial Drive, try these:

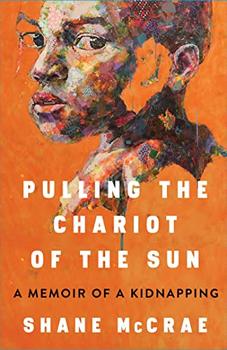

Pulling the Chariot of the Sun

by Shane McCrae

Published 2023

An unforgettable memoir by an award-winning poet about being kidnapped from his Black father and raised by his white supremacist grandparents.

by Wright Thompson

Published 2025

A shocking and revelatory account of the murder of Emmett Till that lays bare how forces from around the world converged on the Mississippi Delta in the long lead-up to the crime, and how the truth was erased for so long.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.