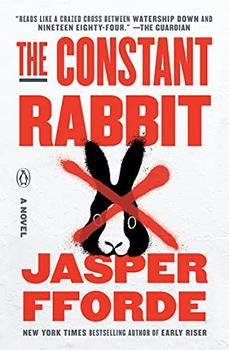

Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The opening scene of Jasper Fforde's The Constant Rabbit shows a Britain where severe austerity measures have slashed public services to such an extremity that "libraries could be open for precisely six minutes every two weeks." The absurdity of this scenario strikes the tone for the novel, which is set in a world where just over one million human-like talking rabbits live in the United Kingdom, and the country is governed by the UK Anti-Rabbit Party (UKARP), a parody of the UK Independence Party (UKIP, see Beyond the Book).

The rabbits became anthropomorphized during an unexplained "Event" in 1965. They are larger than regular rabbits, speak English and "Rabbity," and possess intellectual capacities to outstrip most of the novel's human characters — their choice reading material includes the works of Voltaire and Dumas. Fforde depicts them as both extraordinary and believable, human-like and superhuman. Since the Event, the rabbits have reproduced and developed a culture more courteous and cooperative than that of the humans whom they have lived alongside for the past half-century, albeit not equally. While they are able to undertake the same activities as humans, they are not afforded the same status and are subject to legal and social discrimination and abuse. The Constant Rabbit lands somewhere between science fiction and political satire, presenting a world where the term "bunny" has become a slur.

This world is explained through the first-person narration of Peter Knox, a single father who lives in the village of Much Hemlock. Peter's matter-of-fact tone introduces the outlandish aspects of the novel's reality with straightforward plausibility. Throughout this allegoric whirlwind, Fforde proves himself a master satirist, striking poignant chords with dry wit and playfulness.

The author's adroit storytelling presents the rabbits with both a familiarity and alienness through which to explore fear-driven discrimination, otherizing and prejudice. He weaves historic, cultural and political references throughout the novel, an effort that if done with less skill would have resulted in a clunky narrative. Yet the text is anything but weighty. Instead, it pulls the reader along through a self-aware tale, one that alludes to its own climax in a way that heightens momentum rather than spoiling it.

The catalyst for the events in the novel is the arrival of Peter's former university classmate, Constance Rabbit, and her family in Much Hemlock. The Rabbit family is permitted to live "off-colony," unlike most other rabbits, and move into the house next door to Peter. While Peter does not mind their presence, there is significant opposition to the Rabbits taking up residence in the village. Despite not having anti-rabbit views, Peter works at the Rabbit Compliance Taskforce (RabCoT), a government agency designated with control of the rabbit population.

The Rabbit family's arrival forces Peter to confront his complicity as a human in the unequal society. He is simultaneously aware of his role and reluctant to challenge hierarchical power structures. He rationalizes his employment at RabCoT as a job necessary to pay the bills while reassuring himself that his sentiments towards rabbits are nowhere near as bigoted as those of many of his fellow Much Hemlock residents. This hypocrisy is articulated by one of Peter's superiors at RabCoT:

'And don't say you're not personally responsible…because you are. Your tacit support of the status quo is proof of your complicity, your shrugging indifference a favorable vote in support of keeping things exactly as they are.'

The Constant Rabbit elicits thinking about equality and discrimination. Fforde's ability to instill the gravity of prescient issues of racism and inclusion in the humorously engaging text will anchor these themes in the minds of readers long after the final chapter. The laws, politics and sentiments of speciesism within the novel allow for analogies to segregationist policies. For example, Knox introduces readers to the equivalent of right-wing extremism in his world early on in the book by relating an encounter with a member of the TwoLegsGood (2LG) group:

'We believe in hominid superiority not supremacy,' he replied, parroting a legal ruling that had the latter deemed illegal, yet the former an acceptably realistic view, given the dominance of the species on the planet.

This statement echoes the "separate but equal" doctrine of the legally racially segregated Southern US states. However, Fforde's use of rabbits as allegoric stand-ins for immigrants and racial and ethnic minorities is done in a manner that does not liken people to animals. Rather, the fictional experiences of the novel's rabbits provide a foil for those of marginalized groups in the real world. The application of blatant discrimination against rabbits is so bizarre that it provokes thinking about how some humans treat others. For example, in the opening scene, Norman, a Much Hemlock resident, reacts to a rabbit visiting the library during its fortnightly opening:

'Now then,' said Norman in the lofty tones of someone who believes, despite bountiful evidence to the contrary, that they have the moral high ground, 'let's have a little chat about whether bunnies are welcome in the library, shall we?'

Replace "bunnies" with an equivalent slur for a human and this statement becomes far more sinister.

While there is a clear moral imperative to acknowledge and resist racism and xenophobia at the core of The Constant Rabbit, the author is far from sanctimonious. Rather, he provides wonderfully developed characters, brilliant in their flaws, that serve to demonstrate the importance of this message in their interactions.

One of the most striking achievements of this book is unintentional. Fforde could not have predicted his novel would be released amidst the turmoil of a global pandemic, but he still succeeds in creating a contemporary world so much more bizarre than the actual one, allowing readers to enjoy an amusing escape while also being steered with gentle candor to confront some of the most pervasive social issues of our time.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in November 2020, and has been updated for the

October 2021 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in November 2020, and has been updated for the

October 2021 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked The Constant Rabbit, try these:

by Chuck Tingle

Published 2025

Bury Your Gays is a heart-pounding new novel from USA Today bestselling author Chuck Tingle about what it takes to succeed in a world that wants you dead.

Misha knows that chasing success in Hollywood can be hell.

by John Scalzi

Published 2025

New York Times bestseller John Scalzi flies you to the moon with his most fantastic tale to date: When the Moon Hits Your Eye.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.