Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The title of Lauren Groff's fourth novel, after National Book Award finalist Fates and Furies (2015), refers to the late Middle English definition of the word "matrix," meaning "womb," born from the Latin root "matri," meaning mother. Its significance is cemented through a scene depicting protagonist Marie (based on 12th century poet Marie de France) experiencing a religious vision in which she comes to understand the significance of Eve. Though the purveyor of original sin, without Eve, there would have been no Virgin Mary — "Without the first matrix, there could be no salvatrix, the greatest matrix of all."

This is a conveniently absolving vision for Marie, who is positively brimming with sin. Going back to that Latin root, this is a book about matriarchies, and Marie wants to be the mother of all mothers. The novel begins with Marie arriving at an abbey. She is 17 with a chip on her shoulder, having been cast out of court by Queen Eleanor (based on Eleanor of Aquitaine, see Beyond the Book), who sent Marie away to become a prioress at the abbey, which is plagued by famine and disease. Marie is in love with Eleanor, and it's a love that perseveres all her life, though it is mixed with the fury she feels at being rejected. Marie herself is of English royal blood on her father's side (a Plantagenet), but more important to her is her French maternal lineage — her mother and aunts fought in the Crusades.

As Marie ages, she comes to learn a valuable lesson — "Women in this world are vulnerable; only reputation can keep them from being crushed." Once she's worked her way up to abbess, Marie becomes intent on maintaining her position of power. She orders her underlings to construct a labyrinth around the abbey so no outsiders can come near. She manipulates, threatens and extorts those who question her authority into obedience. She is preoccupied with protecting herself, and always, always, with Eleanor, whose life is recounted in somewhat abbreviated form as Marie learns of her movements and hardships through her network of spies.

Groff's language casts a spell over the reader — words like "misericord" and "cellatrix" and "scriptorium" are plentiful. Characters have names like Amphelisa, Wevua and Wulfhild Thrasher. This language is also used to humorous effect, in early descriptions of Marie, for instance, as "a maiden bastardess," "a rustic gallowsbird," "a giantess of a maiden," "bastard sister of a Norman upstart throne-thieving clan" and so forth. Musical but vaguely grotesque phrases like "Rats have gotten into the groats, the heifers grow goiters and their flesh shrinks against their withers" abound.

Those who need more than these linguistic oddities and inflections for entertainment will find the plot to be substantial and riveting. For a novel that takes place in a convent, there is a surprising amount of intrigue and action, including an unforgettable scene in which the nuns defend the abbey from marauders, hiding in the depths of the labyrinth and springing out to inflict a fairly shocking magnitude of violence.

On a rare visit to the abbey, Eleanor warns Marie that the labyrinth is breeding suspicion and hostility throughout England: "Women act counter to all the laws of submission when they remove themselves from availability. This is what enflames Marie's enemies." Marie's position of power at the abbey and over the surrounding area is anathema because she is a woman, but because Marie is also queer, this statement of Eleanor's points to a broader truth. Women who are sexually unavailable to men have consistently been viewed as unnatural, repellent or dangerous. Many such women have taken refuge in convents and other women-only religious institutions over the centuries, a fact that Matrix alludes to frequently.

It is easy to judge Marie for her pride and naked ambition, but it is also easy to sympathize with her. Brute strength is the order of the day, and she does the best she can with craft and cunning. We know little of the real Marie de France, which makes Matrix all the more impressive. Groff's Marie is made magnificent by her Crusader backstory, chivalrous in her unrequited love, visionary in both religion and the reinvention of herself. Though she is flawed with hubris like the heroes of tragedies, Marie is no Oedipus or Icarus. She is not merely protecting herself, after all, but the entire community of women at the abbey — the Amphelisas, the Wevuas, the Wulfhild Thrashers. Matrix is epic in its scope of history, but intimate and transcendent in its depiction of love among women.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in September 2021, and has been updated for the

September 2022 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in September 2021, and has been updated for the

September 2022 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked Matrix, try these:

by M.T. Anderson

Published 2024

From the award-winning and bestselling author of Feed comes a raucous and slyly funny adult fiction debut, about the quest to steal the mystical bones of a long-dead saint

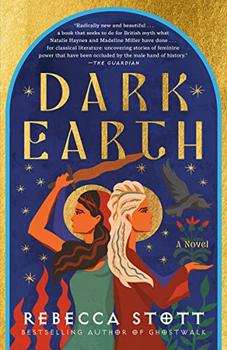

by Rebecca Stott

Published 2023

A captivating novel about two sisters fighting for survival in Dark Ages Britain that casts a thrilling spell of magic and myth.

Most of us who turn to any subject we love remember some morning or evening hour when...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.