Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A novel

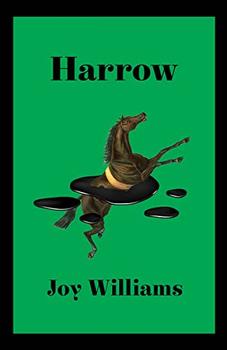

by Joy WilliamsHarrow is the first novel by Joy Williams since Pulitzer-nominated The Quick and the Dead (2000). Like that book, it features disparate plotlines, an abundance of characters and environmental themes. Twenty-one years later, though, the stakes seem higher and Williams writes with greater urgency.

The actual disaster that preceded the events of this dystopian novel is not depicted or thoroughly described. Throughout the book, it is clear that much of the natural world has been destroyed. Plantlife is has been affected and fruit is rare. In one scene, a character is perplexed when another mentions eating an orange. Elsewhere, a character buys pineapple from a scant selection of fruit, all of which is overpriced. In the middle of this is Khristen, an adolescent girl who is shipped off to a Socratic boarding school. When the school closes, she drifts aimlessly with some of her classmates. In her travels, she meets 10-year-old Jeffrey, a child genius preparing for a career as a judge.

Harrow is a difficult book in many ways. There's nothing easy about reading it, which I happen to like. The book replicates the post-apocalyptic haze it depicts: events are vague and fleeting, people come and go with little to introduce or see them off, and even the main character isn't always central. Additionally, it's quite depressing and characters often trade existential platitudes in the same breath as their functional speech. And yet, I'm utterly haunted by it, likely because there's so much left unknown.

Williams' voice is unique and spectacular. She describes things in ways you never knew you needed to hear. A character named Honey says, "We have to live in the now. To try to do anything else is to paint eyeballs on chaos." It's lines like this that make me thrilled that someone is writing such quirky, abstract truisms.

As someone who copes with difficulty by using dark humor, I appreciate how nothing is sacred in the author's jokes. A few times, I cackled so hard I dropped the book. Most of her gallows jokes show a unique perspective on the particular ways people can be tone-deaf. Khristen's mother attempts to console a woman whose child has died by reciting a Zen koan (something like a riddle designed to test a Buddhist's spiritual growth). Later, a Greek tragedy-obsessed 911 operator tells a frantic caller that "disaster can sometimes result in supreme victory." This book incorporates a lot of philosophy, and these moments are fantastic examples of the ways in which wisdom can go wrong.

Hilarious irreverence has long been a hallmark of Williams' writing — her flash fiction collection Ninety-Nine Stories of God is one of my favorites. Her devotion to environmentalism is a frequent subject. Though that term might conjure up images of hemp-clad baristas praising Mother Nature, that's not this writer. "With each election there is the possibility that the environment will become a political issue. But it never does. You don't want it to be," she writes in Ill Nature, a book of essays. If those essays told readers what was coming, then Harrow is saying "I told you so." It didn't feel preachy to me, though. Rather, it reflects the profound grief of someone who's worked so hard to reverse the now inevitable devastation.

That grief is palpable by the third section of the book where now-grown Khristen and Jeffrey meet again. These scenes bring out the humanity in these characters that the plot had previously obscured. There are even moments of great tenderness, such as learning that as a child, Jeffrey "harbored the notion that when someone you were fond of died, it was yourself that disappeared."

Once I finished the book and saw how some themes were resolved, I was better able to view the novel through the lens of a lament and a reckoning. In the last section, threads come together, and suddenly a lot of the plot makes more sense. For instance, by the ending I'd forgotten Khristen's confession that opens the first part: "My mother believed that I had died as an infant but had then come back to the life we shared." As Khristen and Jeffrey speak in the end about Kafka's "The Hunter Gracchus," I brought these ideas together and connected them to other scenes in the book. A tutor talks to Khristen about whether a virus is dead or alive. Khristen's mother asks her much younger lover to describe purgatory. A student named Brittany writes about Gogol's "The Overcoat": "We move overcoat by overcoat toward a dreadful end of which we never think." In Harrow, Joy Williams asks us, in so many ways, how we know if we're alive.

While I've heard that question before, it's never had the impact and resonance that it does now. This book asks readers to give up a lot, to sacrifice a decipherable plot and knowable characters, and to do so through a bleak literary landscape. In return, readers walk away with only some fragments, but they feel tremendously important.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in October 2021, and has been updated for the

August 2022 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in October 2021, and has been updated for the

August 2022 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked Harrow, try these:

by Rachel Kushner

Published 2025

From Rachel Kushner, a Booker Prize finalist, two-time National Book Award finalist, and "one of the most gifted authors of her generation" (The New York Times Book Review), comes a new novel about a seductive and cunning American woman who infiltrates an anarchist collective in France—a propulsive page-turner of glittering insights and dark ...

by C Pam Zhang

Published 2024

The award-winning author of How Much of These Hills Is Gold returns with a rapturous and revelatory novel about a young chef whose discovery of pleasure alters her life and, indirectly, the world

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.