Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

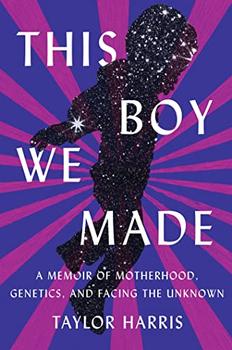

A Memoir of Motherhood, Genetics, and Facing the Unknown

by Taylor HarrisOne morning, Taylor Harris and her husband found their 22-month-old son Christopher, nicknamed "Tophs," awake but unresponsive in his crib. He wouldn't speak or eat, yet eagerly guzzled a bottle of water. They immediately took him to the doctor for blood work. A few hours later the phone call came: "the results are concerning. I'm not even sure they're accurate. You all live close to the hospital, right? I want you to take him to the ER now." Tophs' blood glucose was dangerously low. In the years that followed, Harris and Tophs' doctors looked for answers as to why his body couldn't regulate his blood sugar levels, sometimes leading to seizures, and to why his speech and mental processing remained delayed. All their tests and theories have never amounted to a conclusive diagnosis.

This Boy We Made repeatedly surprised me. I'd assumed it would be exclusively about the medical mystery of Tophs' disability. But Harris elegantly weaves in a lot of other themes, too: mental illness, her own physical concerns, racism, faith, and advocating for her children's health and education. She recalls her teenage struggles with anxiety and the search for a medication regime that would help. A stay-at-home mother of three, she worries she's passed down her mental health issues to her older daughter.

Ironically, the greatest genetic revelation of the book comes from her children's generation. One of Tophs' genetic tests indicates that he has a mutation in the BRCA2 gene — and Harris does, too. The BRCA2 mutation entails a much higher risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer, and though the timing of this discovery is poor — she has just found out she is pregnant with their third child — Harris ultimately decides to have a prophylactic double mastectomy (see Beyond the Book).

The Harris family is based in leafy Charlottesville, Virginia. Harris, from Ohio, attended the University of Virginia and met her husband-to-be on a town trolley in their early 20s. During the years the book covers, her husband is a professor and also attending seminary to become a pastor. They are living elsewhere in Virginia for his in-church training, hoping to return in a few years to set up a congregation, when a white supremacist rally in Charlottesville in 2018 turns into a terrorist attack; they can only watch in horror as the news confirms everything they've ever thought about the town's latent racism.

For as much as I've read about the Black American experience and what can be done to combat racism, I still find it difficult to imagine what it's like to be part of an oppressed minority. That's why I find it so valuable to read accounts like this one that expose the prejudice that exists even in corners of the USA that may seem idyllic to some. In trying to secure medical care and special education for her son, Harris knows she is fighting a system loaded against them:

I also can't ignore the deep divide in Charlottesville. Mostly whites are the haves—the tenured professors, surgeons, bankers, and entrepreneurs—and it's not uncommon to see Blacks in service roles. … As lovely and quaint as Charlottesville can be, you can't forget that many businesses were forced to start serving Black people.

[For] a Black person receiving medical care, the world left no room for humility or deference. We knew too many stories; we'd been warned to look for disparities in treatment, but we didn't really have to be warned. We'd experienced variants of it all our lives. … It's dangerous to be Black and sick.

She suspects quotas and funding matters are stopping her son from getting the extra help he needs before entering kindergarten. Her advocacy for him continues: an uphill battle.

I don't think they know what to make of us. We are middle class. We are highly educated. We are Christians. Yet we weren't overcome with gratitude. … How dare we demand our son receive what is secured by law. This is how Black students, in particular, are railroaded by the American education system every single day.

Harris's strong Christian belief is another aspect of the book I wasn't expecting. Even apart from her husband's pursuit of ministry, she mentions her faith frequently: chastity before marriage, fasting to seek guidance on important decisions and so on. However, she doesn't proselytize, instead using this aspect of her life to give a sense of an important part of her character. Tophs' medical journey, and her own, are framed in terms of faith and doubt. Frequent metaphors of being at sea in a precarious boat, and the language of Before and After, dramatize a life of uncertainty. We may not all face the same physical and emotional challenges as Harris does here, or turn to religion to cope with them, but we all have to come to terms with the unknown.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in February 2022, and has been updated for the

January 2023 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in February 2022, and has been updated for the

January 2023 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked This Boy We Made, try these:

by Carvell Wallace

Published 2025

A transformative memoir that reimagines the conventions of love and posits a radical vision for healing.

by Mary Louise Kelly

Published 2025

Operating Instructions meets Glennon Doyle in this new book by famed NPR reporter Mary Louise Kelly that is destined to become a classic—about the year before her son goes to college—and the joys, losses and surprises that happen along the way.

If passion drives you, let reason hold the reins

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.