Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

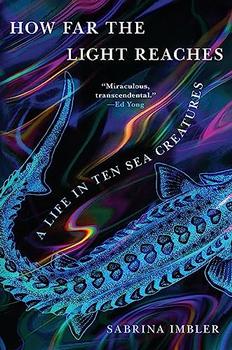

A Life in Ten Sea Creatures

by Sabrina ImblerIn their debut essay collection, science and conservation journalist Sabrina Imbler takes readers on a tour through the ocean's briny depths to meet little-known sea creatures with fascinating lives and capabilities. Throughout, Imbler creates strikingly rendered parallels to their own experience as a queer, mixed race, nonbinary science writer.

In "My Mother and the Starving Octopus," Imbler explores the pitfalls of motherhood and womanhood through the lens of an octopus that brooded over her eggs for an astonishing four-and-a-half years, not leaving them even for a moment to seek nourishment. The account of this creature appears alongside Imbler's memories of developing an eating disorder as a teenager, partly as a result of absorbing their mother's critical comments about her own weight. Though this was a harrowing experience — which included being taken to a "weight-loss coach" and placed on a 1,000 calorie per day diet — Imbler expresses nuanced sympathy for where their mother was coming from: "I realize now that my mother's wish for me to be thin was, in its way, an act of love. She wanted me to be skinny so things would be easier. White, so things would be easier. Straight, so things would be easy, easy, easy." Imbler captures that ineffable moment when one realizes a parent is human, fallible, doing their best even when their best might be harmful.

Elsewhere, Imbler explains that the Chinese sturgeon is known to have traveled 1,900 miles every four years to spawn in the Yangtze River, until the late 20th century, when a series of dams was constructed, blocking access to the spawning site. An account of the sturgeons' plight is placed alongside the story of the author's grandmother's six-month trek from Japanese-occupied Shanghai to Chongqing as a child during the Second Sino-Japanese War — a perilous journey that placed the travelers at the brink of starvation. The easy connection is that both are stories of human-made obstacles to survival, and both stories of resilience. But Imbler takes the dual narratives further, demonstrating how both are also about being uprooted, and whether or not one can ever go home again. The author's grandmother, who now experiences memory challenges, "speaks in Mandarin more and more" as though "she is returning to China," but the China she knew before coming to the United States no longer exists. Her access to it is obstructed, like the Yangtze.

An essay called "We Swarm" is an ode to queer locations and events in New York City, including the annual Pride parade and accompanying Dyke March ("which any of us will remind you is a protest, not a parade"), as well as a stretch of Jacob Riis Beach in Queens that is a popular party spot and hallowed part of LGBTQ+ history (see Beyond the Book). The masses of people that assemble in such spots are compared to salp, "a colonial animal that spends part of its life surrounded by clones of itself," as Imbler discusses the camaraderie and support queer people often extend to one another, whether they be friends or strangers.

In one of the strongest pieces, "Hybrids," Imbler addresses the theme of community again, interrogating language to consider how white supremacy invades and infects self-expression for people of color. Describing an essay addressing their mixed race identity written many years ago, Imbler explains, "I had written the essay not just for a white editor but also for a white audience. Like a dutiful little trash compactor, I had digested my messy heap of an identity into a manageable lesson for people who were not like me." Imbler compares their own experience fielding questions about their racial background ("What are you?") to hybrid sea creatures that have been studied — poked, prodded, named and dissected — by scientists working within disciplines marred by racism, eugenics and colonialism. They go on to write of the sense of connection they feel with those who have had similar experiences — of, for instance, being asked intrusive questions about their race or being mistaken for their white father's wife by strangers. They conclude astutely that "Maybe complaining to someone who gets it is one of the purest comforts on Earth."

The book's guiding concept — sea creatures in parallel to various details of the author's life and identity — is very specific. As such, it's difficult to execute and sustain evenly throughout, and some of the connections are a little strained. But the strongest pieces demonstrate Imbler's impressive range and talent for making both the science and the personal reflections accessible to a wide audience. Their writing is vividly detailed and will be relatable to anyone who has ever felt the particular challenges of being different. Come for the sea creatures, stay for the nuanced coming-of-age journey.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in January 2023, and has been updated for the

January 2024 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in January 2023, and has been updated for the

January 2024 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked How Far the Light Reaches, try these:

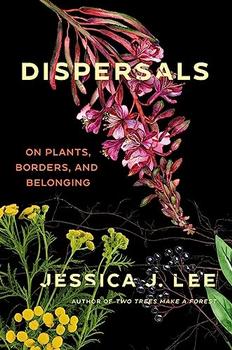

by Jessica J. Lee

Published 2025

A prize-winning memoirist and nature writer turns to the lives of plants entangled in our human world to explore belonging, displacement, identity, and the truths of our shared future

by Chloe Dalton

Published 2025

A moving and fascinating meditation on freedom, trust, loss, and our relationship with the natural world, explored through the story of one woman's unlikely friendship with a wild hare.

When a true genius appears in the world, you may know him by this sign...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.