Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Nancy Hopkins, MIT, and the Fight for Women in Science

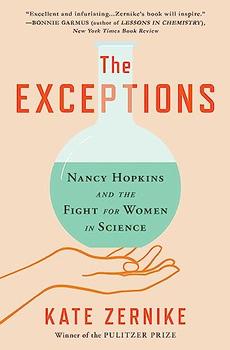

by Kate ZernikeAs debates about "wokeness" roil college campuses, it's important to remember that every action towards equality has engendered an equally strong reaction against it. Just like a law of physics, this push and pull has played out over decades, including at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). There, it took years not just to resolve gender discrimination issues, but even for discrimination in the faculty to be accepted as an actual problem. The story is captured in intimate detail by Kate Zernike in her new book, The Exceptions: Nancy Hopkins, MIT, and the Fight for Women in Science.

The book centers around the experience of Nancy Hopkins who, in 1963, was studying at Radcliffe, which is Harvard's sister school. Harvard didn't accept women as undergraduates for most of its history, only merging admissions with Radcliffe in 1975, although some of Harvard's graduate schools were accepting women by the 1960s.

Hopkins became fascinated with the recent discovery of DNA and was a student of James Watson, one of the Nobel-prize-winning scientists credited with discovering the double-helix structure of DNA (see Beyond the Book). Hopkins excelled in biology, working in Watson's lab and getting her PhD from Harvard. By the early 1970s, she was working at MIT conducting research in their new cancer lab.

But as her career progressed, Hopkins noticed how few women pursued scientific careers and she herself struggled with internal questions about leaving the scientific field to have a family. The women she did meet faced issues such as being passed over for jobs and promotions or receiving lower pay than male colleagues. Yet, Hopkins didn't perceive the challenges as discrimination per se, especially as the women's movement of the '60s and '70s promised greater freedoms and advancement.

She and her few fellow female colleagues viewed gender discrimination as "something from a different era," and they believed that science and academia were a meritocracy—so hard work and dedication would eventually win them the same achievements as their male peers. These female scientists also rejected the label of "feminist" because they believed it meant being a radical.

Over the years, however, Hopkins began to notice certain themes, which will be all too familiar to women reading this today: concern about being perceived as "a bitch or a difficult woman," and the expectation that women would be primary caretakers for children, thus giving men time and space to focus on their work while women struggled to balance caring for sick children or PTA meetings plus work.

Zernike intricately details the inner lives of Hopkins and other trailblazing women who persisted through the slights from their male colleagues and began asking bigger questions about their careers. She also acknowledges the intersection of race and gender, and how the combination of racism and sexism made equality even more elusive for Black female scientists, an important inclusion throughout the book that avoids a whitewashed history of feminism.

By the early '90s, Hopkins was facing multiple crises in her work. A new research direction was exhilarating for her, but she was denied ample lab space for the tools and research staff she needed. Yet when she spoke up her male colleagues didn't believe her—she ended up clandestinely measuring lab spaces at night to provide evidence, like a good scientist. At the same time, male professors tried to push her out of a teaching role and profit from her curriculum for the class by using it for a textbook they planned to sell. All of this led Hopkins to take formal actions to protect her job.

In the process, she realized this wasn't just her—it was part of a pattern. In 1995, her efforts brought together the Committee on Women Faculty to explore if staff were facing true structural discrimination. By the women's own admission, the committee had to include men to be taken seriously—a perfect irony—but the 16 women on the panel presented overwhelming evidence of less pay, fewer opportunities, smaller labs and innumerable indignities.

The report issued by the committee in 1999, which would normally be a dry, academic document in a faculty newsletter, made front-page headlines because the institution was admitting that discrimination existed. It upended the notion that just filling the "pipeline" with more female students would solve inequities at higher ranks. By calling subtle but baked-in discrimination by its name, Hopkins and the committee sparked a shift in viewpoints and actual policies at universities across the U.S.

As uplifting as the ending is, this book can be frustrating for younger female readers. The constant self-blame and assuming that double standards were "the way it is" is difficult to accept. The fact that objectively brilliant women couldn't see patterns or wouldn't question their assumptions for decades—which they sought to do constantly in their scientific work—is astonishing for those who grew up between the Anita Hill hearings and the #MeToo movement.

But, it's important to remember this isn't a clarion call for how things should be. This is a story of how things were, and the fact that some of the smartest, most accomplished women in the world could struggle to see feminism as anything other than "radical," and would have such deep faith in scientific meritocracy despite the contrary evidence, should reinforce for younger generations just how deep-seated and pernicious patriarchal ideas have been, even in living memory.

Ultimately, Hopkins and her colleagues changed the discourse in academia and opened up many eyes to what discrimination actually looks like. With disparities for women and people of color still so persistent, this story and the women behind it benefit us all in these age-old battles for inclusion.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in April 2023, and has been updated for the

March 2024 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in April 2023, and has been updated for the

March 2024 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked The Exceptions, try these:

by Bonnie Garmus

Published 2025

A must-read debut! Meet Elizabeth Zott: a "formidable, unapologetic and inspiring" (Parade) scientist in 1960s California whose career takes a detour when she becomes the unlikely star of a beloved TV cooking show in this novel that is "irresistible, satisfying and full of fuel. It reminds you that change takes time and always requires heat" (The ...

by Cat Bohannon

Published 2025

The real origin of our species: a myth-busting, eye-opening landmark account of how humans evolved, offering a paradigm shift in our thinking about what the female body is, how it came to be, and how this evolution still shapes all our lives today

I have lost all sense of home, having moved about so much. It means to me now only that place where the books are ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.