Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

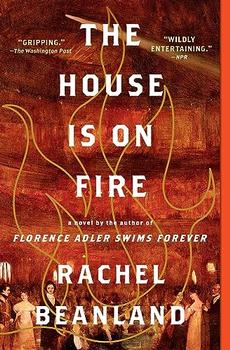

On the night of December 26, 1811, residents of Richmond, Virginia crowded into the local playhouse, not knowing that in a few hours, 72 of them would be burned to death. In Rachel Beanland's The House Is on Fire, we meet four characters who experience that night and its aftermath in deeply personal ways.

Sally, a white widow committed to the well-being of her sister-in-law (who is injured in the fire), is outraged at the treatment of women in the place and time in which she lives. Gilbert, an enslaved Black man who thirsts to make a way for himself and his wife as free people, faces the crisis at the theater with true heroism. Cecily, an enslaved Black woman, companion to a wealthy white woman and the object of desire of her mistress's sadistic brother, sees the tragedy as an opportunity. And Jack, an orphaned white teen, is one of the few who knows how the fire started, but faces tremendous pressure to stay silent.

In any book with four point-of-view characters, each with their own supporting network, readers could get lost in a sea of indistinguishable humanity. This is not a problem with The House Is on Fire. Beanland has created characters so vivid they leap off the page. Each has a deep desire of the heart that seems to them to be unachievable, and each is instantly distinct. For example, Cecily's introduction comes as her mistress is scolding her for being late. Cecily is nursing a lump on the head delivered by her mistress's brother five minutes ago when she tried to avoid his advances. We are immediately in her corner, even before we know she will use the aftermath of the fire to disappear, to be presumed dead and to try to reach freedom.

As the book unfolds, many of the peripheral characters become distinct and memorable as well. Of note is Mary Cowley, a woman known as "native" who is probably actually Black and biracial. She opens her home to the wounded and treats them, giving Sally an outlet to be of use to her sister-in-law and other victims.

For all the protagonists, the disaster interrupts ordinary life and catapults them into crisis mode. As their stories and their social and professional circles overlap, the tapestry of 1811 Richmond comes to life. Gilbert and Cecily are exclusively focused on the needs of the moment, while Sally is desperate to save the life of her sister-in-law and Jack is trying to decide whether to tell what he knows.

In a time and place in history from which the voices of powerful white men are almost all that have been preserved, Beanland chooses to center these characters, who live outside power and influence, to explore the dichotomy between the experiences of Black and white residents as well as the experiences of women and men. One striking disconnect is the lack of heroism displayed by men trying to escape the fire—at the cost of the lives of the women their cultural norms require them to protect—and the fawning praise heaped upon them in the media.

Sally, in particular, latches onto this injustice. Her indignation grows as her brother-in-law refuses to let the doctor amputate his wife's leg, even though leaving her intact is likely to cost her life. Eventually, Sally confronts the editor of the local newspaper to ask him to include women's voices. She also intervenes when an unhinged white slaveowner threatens the life of Cecily's mother. Sally's is a refreshing perspective, reminding us that history books often ignore the experiences of much of the population. While her thoughts on this topic sometimes seem to reflect modern sensibilities, the author believably depicts how a woman of that time might have felt privately, even if she had no outlet for such frustrations.

One disadvantage of a book in the form of an ensemble piece—a story in which multiple characters share the limelight equally—is that none of their stories can be explored as fully as the reader might like. Sally's comes closest to feeling complete, while Gilbert's and Cecily's narratives could be expanded and each sustain a book of their own. And some of the side characters' stories are never resolved at all, even though they are pivotal to one or more of the main characters.

All that aside, it is a great, gripping read. The entire book takes place over three days. Using tight, visceral prose and compact scenes covering a few minutes' worth of action at a time, Beanland creates a breathless, suspenseful pace. She follows up the story with a substantial author's note to clarify which characters and elements of the book are historical and which imagined. This is a page-turner that will leave the reader fired up and, hopefully, reflecting on whether the questions of injustice within have relevant parallels today.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in April 2023, and has been updated for the

April 2024 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in April 2023, and has been updated for the

April 2024 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked The House Is on Fire, try these:

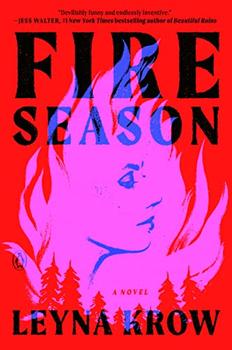

by Leyna Krow

Published 2023

The propulsive story of three scheming opportunists - a banker, a conman, and a woman with an extraordinary gift - whose lives collide in the wake of a devastating fire in the American West.

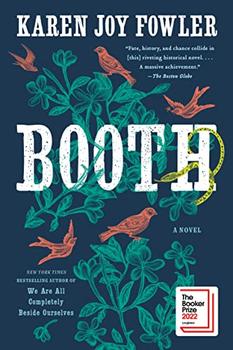

by Karen Joy Fowler

Published 2023

From the Man Booker finalist and bestselling author of We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves comes an epic and intimate novel about the family behind one of the most infamous figures in American history: John Wilkes Booth.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.