Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

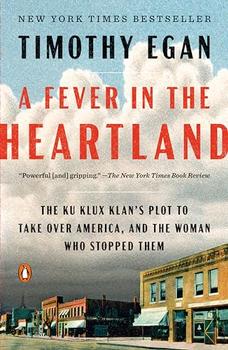

The Ku Klux Klan's Plot to Take Over America, and the Woman Who Stopped Them

by Timothy EganAward-winning author Timothy Egan turns his attention to the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s in his whale of a book A Fever in the Heartland. The story begins in segregated Evansville, Indiana, where a con man named D.C. Stephenson set up shop. His grift: to idealize racial disgust for profit, embracing white supremacy.

At the time, the Ku Klux Klan had shifted from its original conception in the post-Civil War South. Egan explains it this way: "This was a new and expanded roster of enemies for the new and expanding Klan…Hate was tailored to the region—Asians on the Pacific coast, Mexicans in the Southwest, Mormons in the Rocky Mountains, Blacks in the South, Jews on the East Coast, and immigrants and Catholics everywhere."

Stephenson was an odd choice to shepherd a white supremacy movement, since he failed at almost everything he tried. But there he was. Bribing a bunch of Protestant ministers to promote the Klan during Sunday worship services. Sermons preaching white supremacy as a Christian ethic, specifically, preaching that white men were the true Americans, spread throughout Indiana.

Intimidation was the Klan's calling card. Because there was strength in numbers, they visited towns for rallies and parades in large groups. It was a display of force that didn't always land well. For example, when a cohort of Klansmen held a rally in South Bend, home of the Catholic University of Notre Dame, students were enraged and confronted the marchers without care or concern for their own safety. The Klansmen's white hats were ripped off their heads as the protestors mocked their intelligence. "Dunce cap, dunce cap," they chanted, affixing the hats to their own heads.

It was a small victory for resistance. But it didn't change much. Jews were still forced out of their businesses. Black families were run out of their homes. The pointless violence was often based on lies, as when three black teenagers in Marion, Indiana were accused of raping a white woman. Two of the three were lynched in the town square in a picnic-like atmosphere. The woman later confessed she made the story up. Egan's epilogue of the incident: "No one was ever charged with a lawless execution witnessed by thousands of Hoosiers in the public square."

Seeping through Egan's story are similar injustices, examples of how Jews, Catholics and blacks were threatened, bullied and/or killed. It's difficult reading but not alarming. The mild surprise is that a white woman from an Indiana town was brutalized and tormented, not for reasons directly related to white supremacy, but because she was in the clutches of a predator. This supports the idea that angry white men unleash their rage randomly.

Her name was Madge Oberholtzer. She attended the inaugural ball of the newly elected Indiana Governor Edward L. Jackson and sat directly across from Klan leader Stephenson, who was constantly on the lookout for new prey. Oberholtzer was a former sorority girl, a teacher who lived with her parents four blocks from Stephenson. At the ball, he asked her to dance and then gave her his phone number.

Oberholtzer was enamored by Stephenson's charisma. She was naïve about sexually sadistic men, and unaware that he took pleasure in inflicting pain upon women. If any one thing had happened differently — had Oberholtzer not gone to Stephenson's house one night when he called asking her to come, had she stayed home with her parents — perhaps the Klan's presence in Indiana would have remained intact and she would not have died. But she went to Stephenson's house only to endure a 38-hour ordeal of rape and torture. Before her death from taking bichloride of mercury, a poison, she told her story to Asa Smith, an attorney who painstakingly transcribed her version of events, which was read at trial by state prosecutor Will Remy.

Egan's research of this nearly 100-year-old story is detailed and he makes the case that the details were imperative to the results. Oberholtzer's death triggered the death of the Klan. The Klan strategy of bribing and influencing rural men triggered boundless fantasies. One of the more ridiculous ones was that the Klan had the political capital, chops and numbers to win the White House and rule the United States.

There's an argument that such horrifying stories, like those in this book, must be buried forever, cannot see the light of day. But we must revisit the past. Not because we will repeat it. But because we won't. And therefore, we can't make sense of the terrible things our neighbors have done to our neighbors. It's not a leap to say that the worst of people have always damaged the best of people. But what Egan illustrates through this foray into a history rarely told is how American culture continually survives the trauma of its countrymen.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in June 2023, and has been updated for the

July 2024 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in June 2023, and has been updated for the

July 2024 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked A Fever in the Heartland, try these:

by Kellie Carter Jackson

Published 2025

A radical reframing of the past and present of Black resistance—both nonviolent and violent—to white supremacy.

by Mark Whitaker

Published 2025

Published to coincide with the hundredth anniversary of his birth, the first major study of Malcolm X's influence in the sixty years since his assassination, exploring his enduring impact on culture, politics, and civil rights.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.