Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

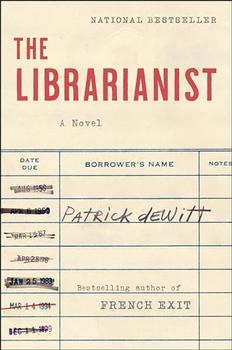

by Patrick deWittPatrick deWitt's The Librarianist begins when Bob Comet, a 71-year-old retired librarian who lives a solitary life in Portland, Oregon, stumbles upon a senior center. "He had no friends, per se; his phone did not ring, and he had no family," deWitt writes, and though Bob isn't unhappy with these circumstances, he's taken with the eccentric group of seniors that he meets, and immediately signs up to volunteer at the center. A lover of literature, he decides to read aloud to the residents; one short story he chooses is Gogol's "The Overcoat," a nod to the type of person one might suspect Bob to be: a tragic everyman, with no life beyond his mundane daily existence. But Bob has faith in the "sideways beauty and harsh humor of the work," as the reader, in turn, learns to have faith in his contentedness and fulfilling inner world.

The Librarianist soon takes us back in time to Bob's childhood, when he discovers novels, and then swiftly to his late teens and early 20s, when he becomes a librarian. DeWitt establishes Bob's solitary, slow, bookwormish existence: his mother dies, leaving him alone in the house they used to share; he begins work at a library, whose head librarian keeps the space especially quiet; he's never had a friend or girlfriend. But he finds fulfillment in his routine, his domestic tasks, his work. And soon enough—at 24 years old—he establishes two meaningful and separate relationships: with Ethan, who lives across the street from the library; and with Connie, who patronizes the library with her father. The reader knows what will happen, because Bob has reminisced about it in an early chapter: Connie, his wife, will leave him for Ethan, his best friend.

Ethan is charismatic, handsome and rakish; the kind of person Bob describes with the line, "when they enter a room, the room changes." Bob tries to keep Connie away from Ethan, lest he seem so obviously inferior in comparison, but their meeting is inevitable. Connie and Bob are already engaged by that point, but Connie and Ethan just can't help falling in love, with Bob reduced helplessly to a supporting character role. He sits at the dining room table as Connie and Ethan clean and joke together in the kitchen. On the day of the wedding, with Ethan as best man, Connie asks a stranger which guy he thinks is the groom, and they all laugh, horribly, when the stranger points at Ethan. The reader's knowledge of what is to come doesn't lessen the ache of its slow arrival; in fact, it perhaps makes these pages more painful by mirroring Bob's subconscious awareness of the situation. Bob must know, on some level, that his marital respite from solitude is only an aberration—a fluke, he calls it later—and his life will eventually regress back to the mean.

Before picking up the plot at the senior center again, deWitt skips back to an episode in 1945; Bob is 11 years old and runs away from home for four days. He stows away on a train, where he meets June and Ida, two traveling thespians who take to him and allow him to accompany them to a hotel on the Oregon coast, where they're scheduled to perform an original show. The two women are eccentric, devoted to each other and their art, utter performers: they speak with an only semi-ironic gravitas, in florid soliloquies and literary metaphors; they talk to him about melancholy and sorrow and regret. The young Bob is captivated and somewhat bewildered; he doesn't say much, but June and Ida seem to appreciate and understand him in a way no one has before, and he does small duties for them, such as walking their dogs and learning to drumroll. Even in the present, Bob still dreams about his days at the hotel, and feels a profound love at the memory, as we have already learned in the novel's first sentences.

But eventually the sheriff recognizes him and drives him home; coincidentally, it's May 8, and the drive takes them through an impromptu parade celebrating the end of World War II (see Beyond the Book)—a detail that could represent a sort of homecoming for Bob, back to books and solitude after a brief but necessary sojourn. Which is to say, Bob is not some loveless, angry Houellebecq character; his aloneness doesn't read as a failure to him or to the reader. Quietude and reading are his life, not an escape from it. On their first meeting, Ethan says, "I keep meaning to get to books but life distracts me." "See, for me it's just the opposite," Bob says, pleased with himself.

In a slightly different book, I think, Bob—with his disposition as the straight man to strong personalities—could easily have been a writer instead of a reader, and The Librarianist could have read as a Künstlerroman in reverse: his friendship/rivalry with the charismatic Ethan would fuel his work; his otherness and powers of observation would allow him to turn life into words; his fateful four days with June and Ida would set him on a path of creation and beauty and life's marrow-sucking. But instead of taking solace in his ability to turn pain into art, using books to justify his loneliness, Bob turns to literature to recognize himself in others, and to not be alone. His reading is described as "a living thing, always moving, eluding, growing, and he knew it could not end, that it was never meant to end"—a beautiful portrayal that makes this lifetime activity sound closer to the creation of art than what people often call the "consumption" of it.

This is not a maudlin novel. DeWitt resists the sentimental; his prose is undramatic and subtly propulsive, and very funny. Bob as a writer-protagonist could also have meant first-person narration—the writer telling their own story—but The Librarianist is in a subtly omniscient third person, with a narrator who gently corrals the reader's sympathies, and who slips infrequently but noticeably into the interiorities of other characters, as if to say: There are other stories here that I could tell, but out of all of them, I'm choosing this one.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in July 2023, and has been updated for the

June 2024 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in July 2023, and has been updated for the

June 2024 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked The Librarianist, try these:

by Michael Deagler

Published 2025

Like a sober, millennial Jesus' Son, Michael Deagler's debut novel is the poignant confession of a recovering addict adrift in the fragmenting landscape of America's middle class.

by Hisham Matar

Published 2025

A luminous novel of friendship, family, and the unthinkable realities of exile, from the Booker Prize–nominated and Pulitzer Prize–winning author of The Return

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.