Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Memoir at the End of Sight

by Andrew LelandThe Believer editor and audio producer Andrew Leland first noticed a change in vision when he was in middle school. On wild nights out with friends in the hills around Santa Fe, he had what he initially dismissed as night blindness, but soon tunnel vision was affecting him seriously. When he was in college, a famous specialist diagnosed him with retinitis pigmentosa (RP) — a genetic condition more prevalent among those with Ashkenazi Jewish heritage, as Leland has — and told him his sight would deteriorate slowly in his 20s and 30s, then rapidly in midlife.

Leland, now in his 40s, has resisted that doctor's prediction by maintaining a gradual pattern of vision loss. In the years that he was writing this book, though, he was coming to terms with his eventual complete blindness and had started using a cane and learning braille. Through his research and travels, he came to feel connected with the disabled community throughout history, finding reassurance that he wasn't alone and that, with the range of assistive technologies now available, he would be able to cope with the challenges of the future.

The title is borrowed from an H.G. Wells science fiction short story, "The Country of the Blind," about an explorer who finds an entire civilization of people born blind. Leland uses the phrase to refer to the blind community in the United States, but also dispersed throughout place and time. He begins, appropriately, with a survey of early hospices and schools where blind people were treated and educated. The first known institution was the Quinze-Vingts in Paris in 1260, a hospital for the blind; its residents were sent out as beggars to earn money, thereby establishing a stereotype of helplessness that has remained ever since. Schools for the blind appeared in Europe in the late 18th century. The first in the US, the Perkins School for the Blind in Massachusetts, was chartered in 1829.

It is common for the blind to enroll in mainstream schooling and then work in the disability field, Leland notes. For instance, he met a graduate of UC Berkeley (a hotbed of disability activism in the 1950s to 1980s) who now works as Amazon's Principal Accessibility Researcher, ensuring that its devices are usable by the disabled. Leland is careful to explain that the privileged — he includes himself in this category — can afford to buy lots of assistive technology, but others are not so lucky. He also exposes in-fighting and ironic discrimination within national disability organizations, where ingrained racism means people of color may not feel represented or comfortable participating.

I was impressed by the intersectionality of Leland's approach. Chapter 4, "The Male Gaze," is particularly interesting, addressing the interplay of blindness and sexuality, with topics including the objectification of women and the public's metaphorical equating of blindness with castration, from Oedipus to Bill Cosby. He also highlights cross-disability movements and ways in which inventions first developed as assistive technology end up being helpful to all: Jacuzzi tubs, closed captioning, typewriters, audiobooks and self-driving cars. Thanks to audio description services, screen readers, e-books with very large print, braille and the Bookshare accessible book repository (see Beyond the Book), Leland remains a reader.

The book is wide-ranging, which some readers may appreciate, but those who pick it up mostly for the autobiographical element may find the profusion of detail on assistive and medical technologies, activists and organizations overwhelming. It is most engaging when we get glimpses of Leland's own blindness journey or go along with him on his travels, such as to a National Federation of the Blind convention in Florida and to one of its residential training courses in Colorado, where he was given sleep shades to simulate total blindness and received lessons in cooking and cleaning.

As well as giving a practical rundown of the various causes of blindness and attempts to mitigate it, the book launches a philosophical enquiry into what it means. Is it a formative trait, or something to be resisted? "Blindness is at once central and incidental," Leland writes, an "experience of relentless, minor cataclysm, folded into the banality of everyday life … [o]ne of the most surprising discoveries I've made is how absolutely ordinary blindness can be." Within an everyday many would think unimaginable, he's found camaraderie. His conversational memoir invites readers to explore his new country with him.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in August 2023, and has been updated for the

August 2024 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in August 2023, and has been updated for the

August 2024 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked The Country of the Blind, try these:

by Claire Oppert

Published 2024

A celebrated art therapist plays the cello for her patients—and offers a moving reflection on the extraordinary power of music to enrich our lives, all the way to the very end.

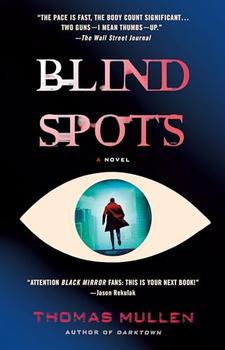

by Thomas Mullen

Published 2024

A riveting crime novel with a speculative edge about the ways our perceptions of reality can be manipulated.

It is among the commonplaces of education that we often first cut off the living root and then try to replace its ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.