Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

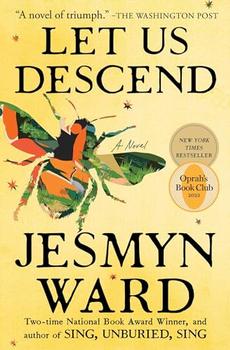

by Jesmyn WardSeparated from her mother and everyone she loves by her enslaver, Annis tries to figure out what remains. A spirit, Mama Aza, has been following Annis's lineage for generations, waiting to be seen. When Annis's enslaver sells her to a plantation in New Orleans, five states away from her birthplace in Virginia, Mama Aza asserts her presence. Annis navigates surviving the brutalities of slavery while learning how to live a life of freedom on her own terms — and how that may involve divine intervention. Jesmyn Ward's Let Us Descend is as horrific as it is beautiful, the definition of grief itself. The way Ward manipulates language is as demanding of attention as Mama Aza; this novel is a force to be reckoned with.

Something that appealed to me on a narrative, structural level is the story's main points of tension. By default, slavery offers its horrors as a tension. Annis's overwhelming grief as she loses people close to her is also a relatively expected narrative layer. Mama Aza's mystical, sometimes sinister presence is a fascinating, unexpected tension that complements Annis's experiences very well. But these tensions are not the only moving pieces of the plot as it unfolds: Ward's novel is also a coming-of-age story. Alongside the bleak reality of her life, readers grow up with Annis, hearing her interests and her desire for freedom, seeing how what freedom means to her evolves.

We cannot talk about Let Us Descend, or even Jesmyn Ward for that matter, without talking about how her novels drip with descriptive language. I especially love the descriptions Ward gives her characters: "Safi's neck flashes with the sun that cuts through the leaves: fresh-cut wood set aflame." Among countless impressive images and phrasings, one linguistic decision especially stuck with me. Ward makes a very intentional choice of referring to those who have bought Annis as "slavers" or "sires" — never as "masters." The absence of "master" throughout is very loud. Language as a tool — both as a weapon to hurt and an instrument of healing — is an important theme, so it is inevitable to consider the omission of the word in the context of Ward's narrative. I observed some of the connotations "master" has for me. Think, for example, especially in a spiritual sense, of how a being can be described as a "master of fate." A master is something or someone who commands. The word has this dominating aura and, in Let Us Descend, the power to deplete Annis of any control or means to truly direct herself. Definitions of "master" that support these connotations include "gain control of" and "overcome" (from Oxford Languages), as well as "victor" and "superior" (synonyms from Merriam-Webster). Yes, Annis being a slave with no legal rights informs the de facto dynamics at play between her and her enslaver, but her enslaver is not a "master" of her entire being. Her narrative is her own, and it is not only commanded by the people or things that subjugate her.

As intriguing as Ward's novel was to me, there are aspects I questioned and that may not be for everyone. One of the hardest challenges of writing a story from the point of view of a slave is creating a sense of hope. By default, slaves lived a life trying to find hope in a world fundamentally devoid of it. Though a little goes a long way to keep Annis afloat, the ending threw me for an unsatisfactory loop, as Ward stretches the novel's sense of hope into something that feels artificial and convenient; I couldn't find the final direction believable. Another part that I had a hard time with was the spiritual aspect. A huge subplot involves the spirit: Is she benevolent? Is she not? What role does she — or should she — play in Annis's life? Many descriptions are ambiguous, and sometimes this got in the way of me visualizing what the spirit looked like or did. I absolutely adore Ward as a writer, and I do enjoy magical realism, however, there were critical moments where I needed to know what was actually going on. I needed more reality, fewer metaphors, to get some narrative clarity. I'm no stranger to novels that require you to work as you read. I just questioned some of the work I was doing to understand Ward's writing for the sake of the story.

Overall, the labor required for reading this book is demanding, but by virtue of what it is, that's unavoidable. We're talking slavery, lyricism, mysticism. These are very tall orders that, depending on your disposition and tastes, you might think drive too hard a bargain.

Nonetheless, it is a beautiful, contemplative read. Every ounce of this book was clearly made with both pain and love; sometimes Ward packs a wrenching mixture of both into a singular page. In these ways, Let Us Descend is worthy of everyone's time and attention.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in October 2023, and has been updated for the

September 2024 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in October 2023, and has been updated for the

September 2024 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked Let Us Descend, try these:

by Percival Everett

Published 2025

A brilliant, action-packed reimagining of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, both harrowing and ferociously funny, told from the enslaved Jim's point of view. From the "literary icon" (Oprah Daily) and Pulitzer Prize Finalist whose novel Erasure is the basis for Cord Jefferson's critically acclaimed film American Fiction.

by Scott Shane

Published 2024

A riveting account of the extraordinary abolitionist, liberator, and writer Thomas Smallwood, who bought his own freedom, led hundreds out of slavery, and named the underground railroad, from Pulitzer Prize-winning author and journalist, Scott Shane. Flee North tells the story for the first time of an American hero all but lost to history.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.