Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The Revolutionary Life of Margaret Cavendish

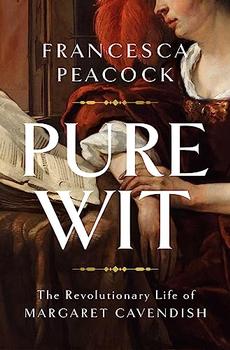

by Francesca PeacockFrancesca Peacock's debut, Pure Wit, is a captivating and well-researched biography of a woman whose contributions to literary history have largely been ignored. Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, was a 17th-century writer of poetry, philosophy, and some of the earliest science fiction. However, beginning in her lifetime, consideration of her creative and philosophical output has come second place to speculation about her eccentricities, relationships, and even her sanity. Pure Wit cuts through centuries of gossip and dismissal to form a clear picture of Cavendish, her life, and her work.

Peacock draws readers in with Cavendish's reputation over the centuries, from diarist Samuel Pepys' fascination with her at the height of her fame in 1667, to her elaborate funeral only seven years later, to Virginia Woolf's dismissal of her as "crack-brained and bird-witted" in 1929. She then gives context both from Cavendish's family history and the wider situation in England during the mid-17th century. Her important life events are intertwined with literary analysis of her work, with the narration moving roughly chronologically through both. For instance, she was deeply affected by the English Civil War, beginning with the invasion of her childhood home by Parliamentarian rioters in 1642. Cavendish and her family were unyielding Royalists, and Peacock demonstrates how their views and the trauma of the war affected both her fiction and philosophical writing.

Peacock also examines Cavendish's views on women and their place in society through her writing and actions. Much of her work either highlights women's strength, as in her play Bell in Campo, where soldiers' wives form their own army and save the day, or criticizes their lack of equality in society, as in her Orations of Divers Sorts, where she states that for women "death is far the happier condition than marriage." Peacock points out, however, that Cavendish often attacks women themselves in these writings. She also discusses Cavendish's depictions of sexuality, including her 1668 The Convent of Pleasure, the first known play written by a woman to depict lesbian desire. Throughout the book, Peacock uses the term "feminist" regarding Cavendish and other women, with the argument that "if the history of feminism were limited to women who expressed their beliefs in women's worth more or less as we do now, it would be a far shorter history than the subject deserves." While this is an excellent point, it's made late in the book. I would have appreciated an earlier and more in-depth explanation of the terms she was using and what she meant by them.

The book also delves into Cavendish's philosophical writing, tracking the development of her thinking and apparent confidence in her own theories, and putting them in context for modern readers. Cavendish developed a theory of vitalist materialism (see Beyond the Book), and strongly opposed the theory of mind-body dualism and the existence of a separate spirit world, though she did later clarify that she believed in God. Peacock connects that philosophy, and Cavendish's difficult relationship with the male-dominated intellectual circles that responded to it, with her story The Blazing World, one of the earliest existing works of science fiction. Peacock doesn't defend Cavendish's authoritarian ideas and failure to understand her opponents'—particularly Parliamentarian opponents'—viewpoints. Instead, she calls for Cavendish to receive the same scholarly attention that other writers of her time have, rather than the dismissal as "eccentric" or "mad" that she has historically been subject to.

To that end, the book's final chapter considers Cavendish's reputation in the four hundred years since her death. Clear patterns have emerged. Often, attention has been focused almost entirely on her biography of her husband, with critics ignoring or belittling the rest of her work and characterizing her as the "perfect wife." Similarly, 19th-century editors picked through her poetry to find examples they considered appropriate for a female author, leaving out or sometimes even rewriting poems they disapproved of. Cavendish has also often been mocked for gossip from her lifetime, including insults questioning her sanity that were taken as fact and built on by later critics.

Peacock neither glosses over Cavendish's flaws nor indulges in the sensationalism that has often surrounded her. Instead, she shows readers a complex person who lived in tumultuous times, and demonstrates her importance to those times and later developments. I would highly recommend Pure Wit to readers interested in either feminist or literary history.

![]() This review

first ran in the February 21, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This review

first ran in the February 21, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

If you liked Pure Wit, try these:

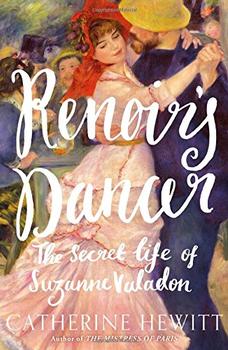

by Catherine Hewitt

Published 2018

Catherine Hewitt's richly told biography of Suzanne Valadon, the illegitimate daughter of a provincial linen maid who became famous as a model for the Impressionists and later as a painter in her own right.

by A.C. Grayling

Published 2017

Out of a 'fractured and fractious time,' the author asserts persuasively, the medieval mind evolved into the modern. Another thought-provoking winner from Grayling." - Kirkus

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.