Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Kinder, Funner Usage Guide for Everyone Who Cares About Words

by Anne CurzanOrdinarily, upon sitting down to write a review of a guide to English language usage, I'd get myself pretty worked up, nervous about ensuring I didn't end a sentence with a preposition or forget what a semicolon is used for. Fortunately for me, Anne Curzan's Says Who? is a different sort of usage manual; its subtitle (A Kinder, Funner Usage Guide for Everyone Who Cares About Words) gives that away right off the bat. Yes, you read that right: Curzan uses "funner" in her book's title, and if that fact gets you ready to fire off an angry email to her publisher, maybe this isn't the book for you. Or maybe, on the other hand, it's exactly the right book to urge you—both playfully and persuasively—to take a different approach to our ever-evolving language.

Curzan is a professor of English, linguistics, and education at the University of Michigan. Many of the examples she incorporates into her book come from the classroom, but not from the sort of fatalistic "kids today just don't understand" perspective that one might expect in a traditional usage manual. Instead, Curzan seems to genuinely relish not only the questions her students ask and the inconsistencies they find in "the rules" but also the ways in which younger generations are reshaping the English language, seemingly right in front of her eyes.

This pleasure is at the heart of Curzan's approach. She divides people into two general camps: "grammandos," a word coined by Lizzie Skurnick back in 2012, meaning "one who constantly corrects others' linguistic mistakes," and "wordies," added to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary in 2018 to describe "someone who delights in language's shifting landscape." If it's not clear already, Curzan would probably place herself more on the side of the "wordies"; although she admits that like everyone who cares about language, she does have an inner grammando, she tries to approach its prescriptive tendencies with more than a little skepticism.

As a trained linguist, Curzan is particularly well-equipped to tackle that task. In addition to intimately understanding how English works, she also has a deep knowledge of the language's historical evolution and of the ways in which her predecessors have dictated what is and isn't "correct" or "standard." Readers will almost certainly find it surprising that some rules that were drilled into elementary school students in the late twentieth century were only recently (and somewhat arbitrarily) defined. When I was learning to write, for example, I would have been told that a sentence like "Hopefully I'm not introducing too many usage errors into this review" should be rewritten as "I hope I'm not..." But that injunction against "hopefully" as a so-called sentence adverb only arose in the 1960s—hardly carved in stone.

More current—and in many ways more relevant—is Curzan's chapter on the use of "they" to refer to a person whose gender is either not known or does not fall into the binary. Curzan offers numerous examples of a singular, gender-neutral "they" throughout literature and in casual conversation. She makes a compelling case that recent objections to this usage of the word are not only un-inclusive, they're at odds with historical precedent.

Curzan makes a similar point in a section about the word "ain't" and about what counts as non-standard English. She argues convincingly, even movingly, that what the so-called experts have labeled "standard" English is just one version of it, and that there are other versions of English, such as African American vernacular, that are every bit as grammatically consistent and coherent, but have been marginalized by virtue of who's doing the judging and who's doing the speaking.

In this way, Curzan's book has a bit of a social agenda, but not one that seems strident or off-putting; instead, it's just part of her inclusive approach to everything from word choice to punctuation to word order (within reason—we still have to understand one another, after all). Curzan strikes a pleasant balance between history and humor, and readers who want to nurture their sense of curiosity about our weird and wonderful language will find plenty here to spark their own inner wordie.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in April 2024, and has been updated for the

April 2025 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in April 2024, and has been updated for the

April 2025 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked Says Who?, try these:

Around the World in Eighty Games

by Marcus du Sautoy

Published 2024

An award-winning mathematician explores the math behind the games we love and why we love to play them.

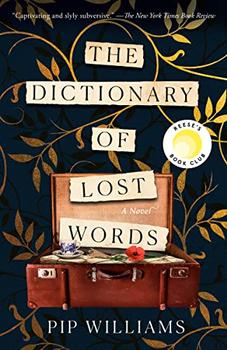

by Pip Williams

Published 2022

In this remarkable debut based on actual events, as a team of male scholars compiles the first Oxford English Dictionary, the daughter of one of them decides to collect the "objectionable" words they omit.

Talent hits a target no one else can hit; Genius hits a target no one else can see.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.