Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Florence Nightingale (1820–1910), known variously as the "Lady with the Lamp" or the "Ministering Angel" of the Crimean War (1853–1856), elevated the role of nursing into a profession—especially for women—in an era that had previously regarded female nurses with disdain. Relying on Nightingale's copious letters and journals and other documentary evidence, Melissa Pritchard's dazzling historical novel Flight of the Wild Swan brings this complex and idiosyncratic woman to exquisite life.

From an early age, Nightingale always knew her purpose. "I am drawn to sickness," the young girl thinks, recognizing that her mother, sister and other female relatives do not share the same feelings. Indeed, "Mama wonders how a family of ducks could have possibly hatched a wild swan like me," she muses in Pritchard's inspired imagining. It is a picture of an outsider looking not in, but always further out … toward the sick, suffering and wounded in heart and spirit.

Through countless brief scenes made up of memories, letters, checklists and "commonplace" journal entries, Pritchard's novel moves cinematically through the formative moments of Nightingale's life. She learns about the natural world from her father "as if I am some creature he must pour all his man's knowledge into … as if to change me into the boy, the son he will never have." Then at seventeen, Nightingale undergoes a trancelike aural communion with God, who speaks to her, saying you are to end the world's suffering. It is the moment that shapes her future course forever:

"In days to come, I will find it odd that my family notices no change in me. They are stupid to the truth I am no longer their daughter or sister, but a creature hunted down, ensnared by God. Cracked in half."

But the strict Victorian codes of her family preclude Nightingale from acting on her call. The next ten long years are agony for her, as she deals with the "daily hysterics" of her older sister, Parthenope, who both envies and resents her desire for independence. Pritchard's portrayal of the sisters is entertaining in the way that sibling rivalries can be, but it also reveals a curious side to the younger Nightingale: an impatience with anything not concerned with her calling, which accounts for periodic callousness toward her immediate family. This insensitivity draws a deeply ironic contrast to the woman who would eventually wander with her lamp at night among the scores of wounded and dying soldiers in the Crimea.

Indeed, it is the Crimean War where Nightingale's mettle is forged against a resistant male-dominated medical establishment, a never-ending shortage of medicine and supplies and the appalling sanitary conditions that kill more men than battle wounds (see Beyond the Book). When Nightingale and the contingent of nurses she manages arrive at Scutari Hospital, a "white-washed monstrosity," in November 1854, they encounter a slaughterhouse.

Pritchard's judicious use of letters and different points of view from Nightingale's friends and sponsors at home—like Sidney Herbert, the acting Secretary at War—helpfully broadens the story's scope. However, Pritchard's inclination to paint Herbert as Nightingale's lifelong, unrequited love seems a bit out of place, as history speaks of them only as close friends and confidants with a shared interest in reform.

Pritchard lavishes imagery, often haunting and heartbreaking, of Nightingale at her best among the worst suffering imaginable:

"Burials cannot keep up with deaths; the stink of rotted, putrid flesh is everywhere. The slow swing of her lantern with its single flicker of flame becomes a nightly occurrence in the wards. Were she an artist, she would not paint Christ washing Peter's feet in a golden bowl while the other disciples turn the pages of books, talk, wait their turn. Nothing like Tintoretto. Hers would be a chiaroscuro portrait of agony, blood, desolation, and death."

The most powerful passages in Flight of the Wild Swan reside in the cauldron of the Crimean War, as Pritchard peels back the layers of a woman worn down to the bone—and the spirit—by meaningless suffering and death. Nightingale changes in noticeable ways to her friends, with her "new habit of holding herself in a state of perfect stillness while one foot frenziedly taps out her irritation with someone's slowness, stupidity, or ignorance." She leaves the Crimea broken down by illness at war's end, but still determined to live out her calling. The final quarter of the book takes large leaps through the rest of Nightingale's long life, with a conclusion that both satisfies and leaves the reader wanting to know her more. Pritchard anticipates the reaction and provides a helpful list of recommended reading.

Flight of the Wild Swan is a capacious and tremendously written novel, one that blends history, fiction and a nuanced vision of the "wild swan" herself. It is a story to read, reread and share with others.

![]() This review

first ran in the April 17, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This review

first ran in the April 17, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

If you liked Flight of the Wild Swan, try these:

by Abraham Verghese

Published 2025

Winner: BookBrowse Fiction Award 2023

From the New York Times–bestselling author of Cutting for Stone comes a stunning and magisterial epic of love, faith, and medicine, set in Kerala, South India, and following three generations of a family seeking the answers to a strange secret.

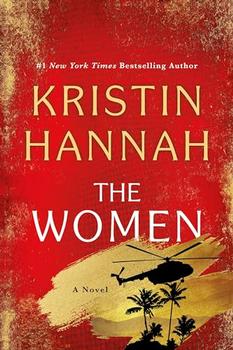

by Kristin Hannah

Published 2024

From master storyteller Kristin Hannah, #1 New York Times bestselling author of The Nightingale and The Four Winds, comes the story of a turbulent, transformative era in America: the 1960s.

The library is the temple of learning, and learning has liberated more people than all the wars in history

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.