Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

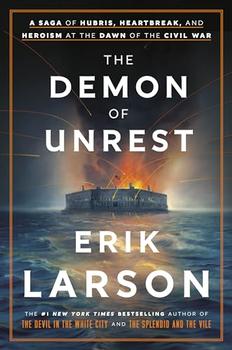

A Saga of Hubris, Heartbreak, and Heroism at the Dawn of the Civil War

by Erik LarsonIn the aftermath of the 1860 presidential election, the divided United States began to collapse as South Carolina seceded from the Union, followed by another six Southern states. Among the countless contentious points between the Union and the fledgling Confederacy was the existence of a 75-man Federal garrison in Charleston Harbor that would become the flashpoint for civil war. In The Demon of Unrest, Erik Larson weaves a gripping tale of America's slow-motion lurch toward war, placing the reader inside events as they unfold.

In seeking to answer what "malignant magic" could lead Americans to consider the unthinkable—a bloody civil war—Larson prefaces his narrative with the parallels between the "national dread" felt during the run-up to the certification of the Electoral College and the presidential inauguration in 1861 with that during the Capitol assault of January 6, 2021 (as electoral votes were counted). Dread is the watchword, and readers will experience it anew in Larson's taut telling.

In seven dramatic parts, The Demon of Unrest unfurls those eventful months in 1861, centering the stories of memorable individuals such as Major Robert Anderson, Union commander of Fort Sumter; Edmund Ruffin, fire-eating evangelist for Southern secession who fired the first shot at Fort Sumter; Mary Chesnut, the acclaimed Southern diarist and wife of a prominent planter and politician; and, of course, an embattled Lincoln ringed round by presumptuous allies and politicians who believed they knew better how to handle the crisis.

Traveling from Washington, D.C., where lame duck president James Buchanan's inaction bordered on treason, to the heady excitement of the newly formed Confederate government in its first capital of Montgomery, Alabama, Larson sharply dissects the Union's fresh cadaver in the months prior to the Sumter attack and posits that a wounded sense of honor warped Southern political sensibilities and befuddled Northern peacemakers eager to bring the secessionists back into the fold. Lincoln's stubborn belief, based "on basically no evidence," that a vast swathe of pro-Union sentiment still existed in the South after the defection of seven states reveals a startling naivete, Larson observes, and may account for the exceeding caution with which the new administration considered whether to resupply and reinforce Fort Sumter.

Larson's most incisive analysis scrutinizes the Southern planter aristocracy that called themselves "the chivalry." Here, Larson reveals a society bred and fed upon the tales of Sir Walter Scott, enamored of military titles and uniforms. Their simulacrum of nobility, Larson writes, was "affirmed on a daily basis by the fact of their possession of, and dominion over, a subservient population of enslaved Blacks." Valuing honor above all human traits, the chivalry "would happily kill to sustain it." It was a code duello mentality, and it symbolized a South stuck in time. Larson's most powerful analogy is that of South Carolina as Miss Havisham from Charles Dickens's Great Expectations: left at the altar of the Railroad Age, she stops her clocks and leaves the world behind, retreating into her "own world of indolence and myth."

Excavating a wealth of official documents and secret communiques, Larson crafts a thrilling tale with tick-tocking suspense around the book's prime target: Fort Sumter. Indeed, the true hero in Larson's telling is Anderson, a U.S. officer sympathetic to the South who nevertheless did everything in his purview (and beyond) to maintain his position and protect his soldiers from imminent attack. It was Anderson's secret decision—made without consulting the then-Secretary of War John B. Floyd, soon to defect to the Confederacy—to move his command, under the cover of Christmas night, from Fort Moultrie on the coast to the more defensible Fort Sumter in the middle of the harbor (see Beyond the Book). His cunning and situational awareness is even more impressive in the wake of long silences and confusing directions from Washington; Larson clearly admires him, as will the reader. Anderson's steadfast defense of Sumter, which became "a cauldron of heat, smoke, and lacerating shrapnel" for two April days under intense Confederate artillery fire, would cement his celebrity in the North after the stockade surrendered on April 13 and sailed for home on April 14.

Interspersed with the politics and intrigues are a raft of other appealing and appalling characters who orbited the Sumter drama, with James Henry Hammond a prime example of the latter. An ex-governor of South Carolina and senator who gave the historic 1858 Senate address that "Cotton is King," Hammond was a member of the chivalry, a pro-slavery advocate who "worked his slaves hard" and barely recovered politically from a sexual scandal including four of his nieces. More palatable is the bemused and observant Sir William Howard Russell, The Times of London's special correspondent, who wrote about his meetings with prominent people North and South. Larson outlines Russell's keen conviction that "Northerners had little understanding of their brethren below the Mason-Dixon Line" and that Southerners viewed their Northern counterparts as cowards. Russell's writings captured both sides' central misunderstanding of "the other," which led to missteps and miscommunications between Lincoln's administration and the Confederacy during these key months.

Adding an indelible sparkle to the narrative are Larson's plumb pickings from Mary Chesnut's diary. A reliable source of comedic relief, Chesnut chronicles the mood and spirit of the Confederacy as she goes "social spelunking" in Montgomery and Charleston. Included is Chesnut's lighthearted "flirtation" with South Carolina's handsome ex-governor and bon vivant John L. Manning, a source of friction with Mary's husband, James: "After dinner, Mr. Chesnut made himself eminently absurd by accusing me of flirting with John Manning, &c. I could only laugh—too funny!" Known mostly from her folksy inclusion in Ken Burns's iconic documentary The Civil War, she is discussed in all her contradictions by Larson. "Mary had a clear-eyed view of slavery," Larson writes, accepting it as a foundation of Southern society even as she was honest about and spoke against the sexual abuse of enslaved girls and women at the hands of white slaveowners. She is an enigma of sorts, but a categorical delight to discover through the pages of her diary.

Covering the dicey days leading up to war, The Demon of Unrest is cinematic in scope, intimate in detail and charmingly written. Even more importantly, the parallels of 1861 with the electoral riots of 2021 make this book an urgent call to learn from history's mistakes. This is narrative history at its best: instructive, timely and utterly enthralling.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in May 2024, and has been updated for the

December 2024 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in May 2024, and has been updated for the

December 2024 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked The Demon of Unrest, try these:

by Clint Smith

Published 2022

The Atlantic staff writer and poet Clint Smith's revealing, contemporary portrait of America as a slave owning nation.

by Louis Bayard

Published 2020

From the prizewinning author of Mr. Timothy and The Pale Blue Eye comes Courting Mr. Lincoln, the page-turning and surprising story of a young Abraham Lincoln and the two people who loved him best: a sparky, marriageable Mary Todd and Lincoln's best friend, Joshua Speed.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.