Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

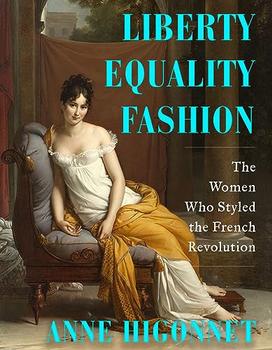

The Women Who Styled the French Revolution

by Anne HigonnetWith the title Liberty Equality Fashion, it may seem like Anne Higonnet's new book is an unserious work—maybe a picture book of dresses from revolutionary France, recalling the refrain of "liberty, equality, fraternity" that dominated in 1789. But this would be an incorrect assumption. An exhaustive history of the French Revolution this is not, but the book masterfully explores the confluence of social, political and economic factors that allowed for a sea change in something as basic as what women wore each day. Equally important are the author's insights on how clothing mirrored the expansion of opportunities for women and the reactionary reversals following a brief moment of progress.

This is the story of three women who created a new style in revolutionary France and whose celebrity status drove the adoption of their radical fashions by others. Joséphine Bonaparte (who was Rose de Beauharnais throughout much of this story), Térézia Tallien and Juliette Récamier all began their lives as outsiders. They weren't particularly wealthy nor important members of the nobility, and Joséphine was born outside of mainland France in the colony of Martinique.

All three endured unhappy arranged marriages and were lucky to escape the Terror of 1793-94 with their lives. Joséphine and Térézia had even been imprisoned and threatened with the guillotine; the former was arrested because her husband was a minor noble, which was enough to earn the ire of the Committee of Public Safety, and the latter was swept up in one of the large-scale arrests that took place regularly.

Following this harrowing experience, they became best friends and soon invented a new style of dress—flowing cotton, no corsets or petticoats, and simple sashes under the bust or at the waist. Between 1794 and 1796, with Térézia's salon functioning as the most fashionable place in town, she and Joséphine (still called Rose at the time—Napoleon would make her change her name later) took the world by storm with their free-flowing, downright comfortable dresses that replaced the elaborate gowns of the ancien régime. Juliette popularized it too in her own salon, presenting herself in virginal white at all times, which became her signature style.

Following this harrowing experience, they became best friends and soon invented a new style of dress—flowing cotton, no corsets or petticoats, and simple sashes under the bust or at the waist. Between 1794 and 1796, with Térézia's salon functioning as the most fashionable place in town, she and Joséphine (still called Rose at the time—Napoleon would make her change her name later) took the world by storm with their free-flowing, downright comfortable dresses that replaced the elaborate gowns of the ancien régime. Juliette popularized it too in her own salon, presenting herself in virginal white at all times, which became her signature style.

This isn't simply a story of new dresses, though. Higonnet deftly weaves together the larger social elements that made this fashion moment possible, including the assertion of individual freedoms in the Revolution, the societal release of tension after the Terror, and the existence of new sources of inspiration from colonial lands. She explains how cotton and muslin from India gave women new options beyond costly silk, and how the styles of Black and Creole women in the French colonies inspired Joséphine (and by extension, her best friend Térézia). Higonnet also notes how Marie Antoinette unwittingly set a precedent with a 1783 portrait in a similar dress, but Térézia and Joséphine presented it as authentic and populist, whereas Antoinette was perceived as a monarch cosplaying as a peasant (see Beyond the Book).

This new style was reminiscent of classical Greece and Rome, which were consistently popular themes in 18th-century Europe, but these women took it in their own direction with new fabrics, madras prints from India, pashmina scarves—even bringing handbags into fashion. Notably, as Higonnet points out, this style of dress was accommodating of pregnancy and women's actual physical needs, unlike constrictive corsets. She shows how this fashion revolution not only put the leading style within financial reach of more women, but also made clothes actually pleasant to wear for women of any shape, size or maternity status.

As with all revolutions, though, there was the inevitable backlash. First, it was male hysteria claiming that French women were dousing their white gowns in water and walking around wet, freezing and practically naked (they weren't). Eventually, Napoleon began micromanaging Joséphine's wardrobe and demanding that she dress more "appropriately" for an empress. The overbearing pre-Revolutionary dresses roared back, and although Térézia and Juliette remained fashion icons, the moment of their style passed once Napoleon consolidated his power.

By delving into the actual forms, fabrics and feel of women's fashion, Higonnet helps the reader understand how difficult it was just to move in a corset, and conversely how freeing these cotton one-piece dresses truly were. She also explains why this freedom was disturbing to a patriarchal society: "Revolutionary fashion was resisted not despite its comfort, or despite the mobility it granted women in public. Revolutionary fashion was resisted because of its comfort, and because of the mobility it granted women in public" (emphasis added).

Her discussions of race relations and the impact of colonialism show how cultural contacts have played a role in setting styles for centuries, and we even get a glimpse into how the 18th-century versions of influencers came to be—beautiful women famous for the sake of being famous is much older than we may think.

This book won't explain all the workings of the French Revolution or Napoleon's rise to power, but it will make you look differently at an empire-waist dress.

Portrait of Madame Récamier by Jacques-Louis David, 1800, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

![]() This review

first ran in the May 15, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This review

first ran in the May 15, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

If you liked Liberty Equality Fashion, try these:

by Hilary A. Hallett

Published 2024

The modern romance novel is elevated to a subject of serious study in this addictively readable biography of pioneering celebrity author Elinor Glyn.

by Nancy Goldstone

Published 2022

The vibrant, sprawling saga of Empress Maria Theresa - one of the most renowned women rulers in history - and three of her extraordinary daughters, including Marie Antoinette, the doomed queen of France.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.