Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

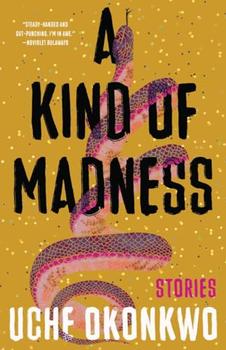

The word "madness," like many others that can be used to stigmatize mental illness — e.g., "crazy," "insane," may be falling out of fashion even as its vaguely dramatic tone preserves a romantic, timeless connotation. But while Uche Okonkwo's debut story collection A Kind of Madness touches on mental health in the scientific and medical sense, it also expands and subverts the meaning of "madness," often reflecting it away from individual people and onto the chaotic, cruel, nonsensical features of the atmosphere around them.

The stories range across contemporary Nigerian life, depicting numerous human versus society dilemmas, with protagonists believing, frequently to both humorous and tragic effect, that they can control their circumstances through sheer force of will. In "Nwunye Belgium," a mother attempts to marry off her daughter to a Belgian doctor for financial security, and the daughter must contend with her mother's insistence and the disruption of her engagement to another man. In "Shadow," a young boy who feels unappreciated at home fantasizes about being adopted by a beloved aunt and becomes determined to make that fantasy a reality. In "Animals," a child gives the chicken his mother intends to slaughter for soup a name — Otuanya — thinking that by doing so he may be able to change the bird's fate and convince his family to keep it as a pet. In "The Girl Who Lied," a boarding school student challenges herself to perform daring and attention-garnering feats that her best friend begins to recognize as a way of coping with hidden pain.

Okonkwo excels at creating suspense. Even when characters seem to attempt the impossible, or appear to be setting themselves up for inevitable failure, we wonder if they will somehow manage, a feeling that is frequently achieved through the unsullied and resourceful perspective of children. The most nail-biting example of this may be "Eden," in which a brother and sister's curiosity is piqued by a pornography tape belonging to their father that resides in the back of a cupboard, "that dark, dusty place where the films were older than God." As their neighborhood experiences regular blackouts due to power cuts and their family cannot afford a generator, we know it is only a matter of time before the cassette gets stuck in the player — an absurd but completely realistic example of how socioeconomic factors can directly inform traumatic childhood events. What happens next sends the brother, Madu, into a state of confusion about what it means to be "good," and Ifechi, the sister, into the determination that she is "bad." These ideas are, of course, imposed on them by adults. There is no escaping the domination of the grown-up world for them, but the children's handling of the situation is touching, as even in their exploration of adult sexuality and the harshly gendered expectations attached to it, an undertaking that seems like it should divide them, they still seek to protect and emulate each other, however imperfectly.

Another moving example of relationships between children emerges in "Milk and Oil," about the fast friendship of two girls affected by the fact that one of them has sickle cell disease (see Beyond the Book), a condition that the other at first fails to understand. This story stands out for offering more resolution than many. Endings in A Kind of Madness often come abruptly, and insofar as plots conclude they frequently do so more or less exactly the way we think they will, but the book's central value is in how character and story intersect — the quiet rebellions that children or adults enact even when they know they must cede to a higher authority, the deliberate decisions they make even when these decisions may benefit no one.

What all of the narratives have in common is that they vividly highlight the twisted machinations and mysteries of everyday lives. They uncover the bizarre notions that people and communities are compelled to accept as shared currency, the sinister controlling forces that exist beneath the surface of supposedly innocent and normal interactions. With its meticulously crafted language and storytelling, A Kind of Madness is quiet but bold, a striking and confident debut.

![]() This review

first ran in the June 5, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This review

first ran in the June 5, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

If you liked A Kind of Madness, try these:

by Afabwaje Kurian

Published 2025

Set against the backdrop of 1970s Nigeria teetering between post-colonial dependency and self-rule, Before the Mango Ripens examines the enduring themes of faith, disillusionment, and the search for belonging. Both epic and intimate, Afabwaje Kurian's debut announces a brilliant new talent for readers of Imbolo Mbue and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.

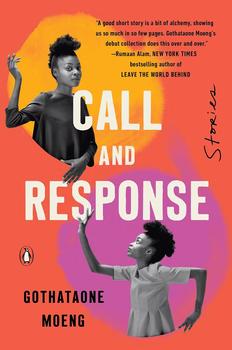

by Gothataone Moeng

Published 2024

Richly drawn stories about the lives of ordinary families in contemporary Botswana as they navigate relationships, tradition and caretaking in a rapidly changing world.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.